Story Types: Jackie's Story

In 1947, when Jackie Robinson signed his contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, he told the waiting press, “I fully realize what it means – my being given this opportunity – not only for me, but for my race and baseball.” Throughout his life, he would insist that being the first Black person in a given vocation didn’t matter unless there were a second, third, fourth, or more to follow through the door he had opened. For Robinson, that meant supporting Black athletes across all sports—not just the men who followed him into the major leagues. One such collaboration was with trailblazing tennis star Althea Gibson, with whom Jackie Robinson worked closely during the 1950s and 1960s, as she strove to break down barriers in women’s tennis and golf.

Jackie Robinson presents Althea Gibson the 1950 Sports Achievement Award from the Harlem Branch of the YMCA at its annual Century Club dinner. Executive Director Rudolph J. Thomas smiles in approval. Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries

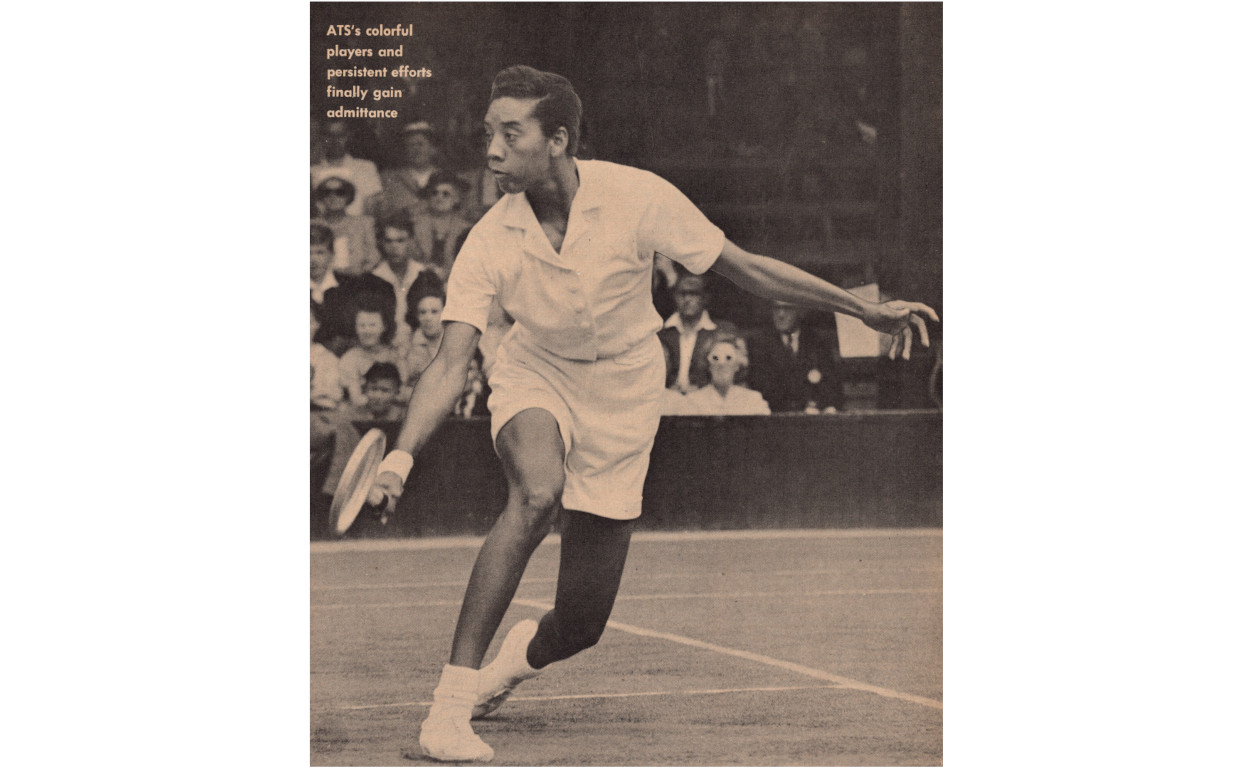

Althea Gibson won multiple singles, doubles, and mixed doubles Grand Slam titles across her amateur tennis career in the 1950s. After tennis, she turned to golf, becoming the first Black player on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour in 1964. Throughout her life, Gibson was confronted with Jim Crow barriers in both sports. In the early phases of her tennis career, even getting on the court was a challenge. To qualify for larger tournaments, players needed access to the highly segregated world of private tennis clubs, from which African Americans were frozen out entirely. Gibson was skilled—the entire tennis world knew it—but she did not receive an invitation to compete in the 1950 U.S. National Championships until a retired white player, Alice Marble, fomented public support for her inclusion. Over the decade, her legend grew—she won back-to-back Wimbledon singles titles in 1957 and 1958 and amassed three doubles titles there as well.

Althea Gibson shows Jackie Robinson her racquet grip at the American National Theatre Academy tennis tournament at the 7th Regiment Armory on February 16, 1951. Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images

In 1951, Althea Gibson joined Jackie Robinson in a celebrity tennis tournament to support the American National Theatre Academy. While the event might have featured more goofs and gimmicks than actual tennis competition, it was a chance for Robinson to support a rising star in a white-dominated field. Robinson himself was a competent tennis player. In 1936, he won a junior singles title at the Pacific Coast Negro Tennis Tournament, and he was victorious in both men’s singles and doubles in the Black Western Federation of Tennis Clubs tournament in 1939, even though he only played when not busy with other sports.

Althea Gibson receives a ticker-tape parade in New York on July 11, 1957. The Detroit Tribune

Prior to the Open Era in tennis, major tournaments such as Wimbledon were restricted to amateur players, who were not permitted to accept prize money. As a result, Gibson struggled to make ends meet, despite holding multiple Grand Slam titles and being honored with a ticker-tape parade in 1957. She turned pro in 1958 but found opportunities there to be equally lacking. Businesses were uninterested in sponsoring a Black player, and the prize money from tournaments was still small. “I saw that white tennis players, some of whom I had thrashed on the court, were picking up offers and invitations,” she later wrote in 1968. “Suddenly, it dawned on me that my triumphs had not destroyed the racial barriers definitively…Or, if I did destroy them, they had been erected behind me again.”2 Like Robinson, she tried to supplement her income with other ventures. She tried her hand at singing and acting, participated in exhibition tours, and published an autobiography. Nonetheless, commercial success eluded her.

Jackie Robinson and Althea Gibson examine a scorecard at the North-South tournament in February 1962. Bettmann Archive, Getty Images

Gibson hoped that more opportunities awaited her in golf. As she sought to enter the top ranks of a new sport, she received even more brutal Jim Crow treatment than she had in her tennis career. She competed at country clubs at which she could not use the dressing room or eat in the restaurant. Adding to her personal struggles, golf didn’t pay the bills. Nonetheless, she took joy in the game and participated in celebrity tournaments. In 1962, Gibson competed in the North-South golf tournament in Miami, alongside Jackie Robinson and retired boxer Joe Louis. Robinson and Gibson won the men’s and women’s tournaments, respectively. That summer, the pair teamed up against Louis and Ann Gregory, another top Black golfer, at a celebrity match held just outside of Chicago. Again, Robinson and Gibson emerged victorious, showing both players’ strengths as multi-sport athletes. Gibson went on to earn her LPGA tour card in 1964, making her the first Black golfer to do so.

Althea Gibson appears in the May 1953 issue of Our Sports. Edited by Jackie Robinson, Our Sports was a magazine that highlighted Black competitors – including women – in a wide variety of sports alongside professional ballplayers. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Althea Gibson’s renown as a barrier breaker—in two sports—often went unheralded in the press, let alone in her pocketbook. Still, she was an inspiration to Black athletes, especially women, in an era when the Civil Rights Movement was still in its infancy. Both Althea Gibson and Jackie Robinson used their status to promote desegregation in American sport. Unlike Robinson, Gibson was much less outspoken about the growing fight for civil rights. As she was racking up accolades, she often struggled to talk about how her triumphs and misfortunes were reflected in the broader American society. She was criticized often in the Black media for her lack of public participation in the movement, especially as later Black tennis stars, such as Arthur Ashe, were more outspoken. Even so, the power of Gibson’s legacy is undeniable; Black women tennis stars, such as Venus Williams, Serena Williams, Naomi Osaka, and Coco Gauff, dominate on the global stage today, made possible by Gibbs’ pioneering efforts in the 1950s and 1960s.

In the early 1960s, Jackie Robinson aided Martin Luther King, Jr., and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement as they fought for desegregation and economic equality across the American South. Robinson—not a trained organizer, minister, or labor leader, but a renowned and outspoken athlete—added his voice to the struggle wherever and whenever he was asked. In May 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, was the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement. From May 2 to May 10, over 1000 children marched in the streets to end segregation, in what later became known as Birmingham’s Children’s Crusade. White supremacists responded to the protests by bombing two locations where movement leaders gathered on May 11.

As these events were unfolding, Robinson was spearheading the “Back Our Brothers,” fundraising campaign that sought to channel desperately needed resources from donors in the North to movement leaders on the ground in the South. He would host an organizing luncheon on May 7 in New York City that raised $8000 to directly support the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Birmingham. At the luncheon Robinson read a telegram he sent to President John F. Kennedy, advising, “The revolution that is taking place in this country cannot be squelched by police dogs or high-powered hoses.”

That week, as images of police violence were broadcast on televisions across the county, Robinson watched in horror. Close to eight hundred youth protestors were arrested by the Birmingham Police Department in an attempt to stop the marches. On the second day of the protest, the police blasted the children with fire hoses and attacked them with dogs, injuring many. This reinforced Robinson’s resolve to join the marchers in Birmingham and he began to plan his visit.

“Ex-Baseball Star to Join Big Protest,” May 8, 1963. The Associated Press Wire

On May 11, two days before Robinson went to Birmingham, white supremacists bombed the home of A.D. King, the brother of Martin Luther King, Jr., while the family sat in their living room. Like his brother, A.D. King was a politically active minister, which made him a target for the Ku Klux Klan and the local police. Later that night, another bomb was detonated at the A.G. Gaston Motel, where many civil rights leaders stayed when they visited Birmingham, causing widespread destruction.

In the midst of these aggressions, incremental progress was being made: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was nearing a desegregation agreement with Birmingham’s white civic leaders and businessmen, and the child protesters were being released from jail, where many had languished for over a week.

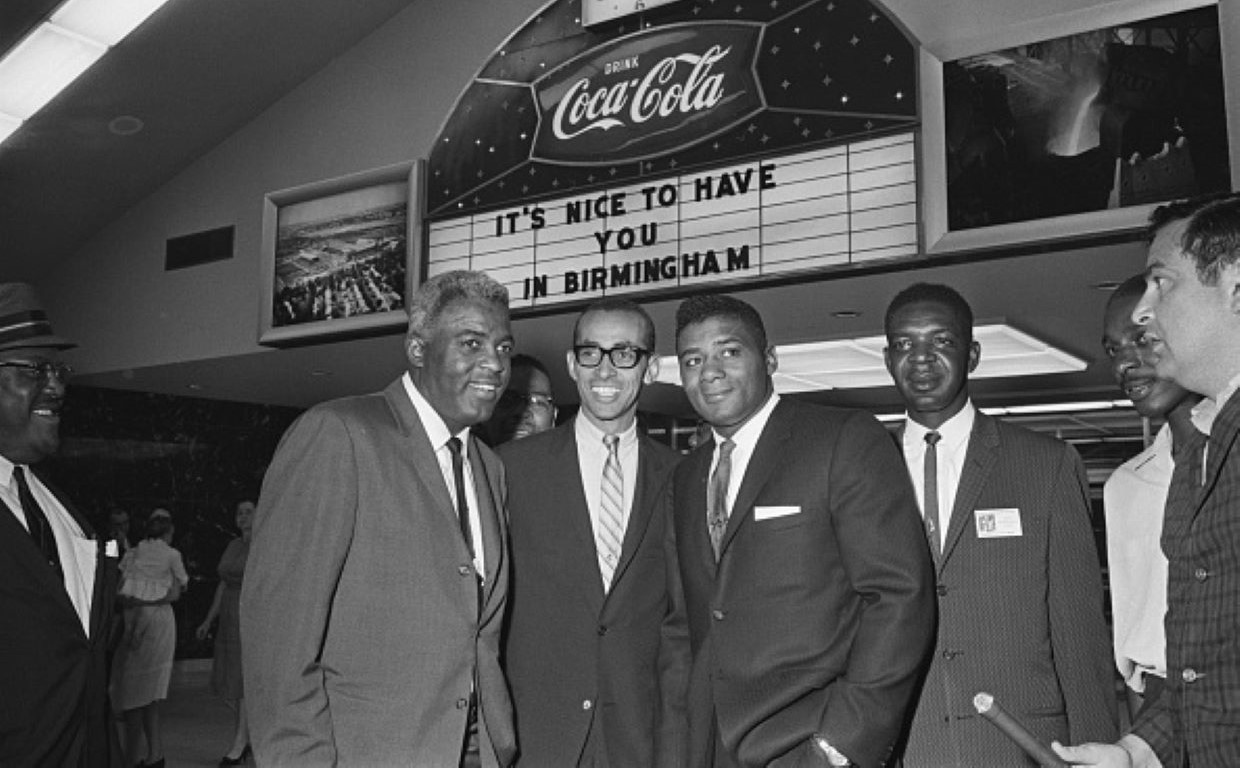

Jackie Robinson, Wyatt T. Walker, and Floyd Patterson at the Birmingham airport on their arrival late May 13, 1963. Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

On the evening of May 13, Robinson and boxer Floyd Patterson arrived in Birmingham to lend their assistance. They immediately drove to the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church where they were joined by Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and other Birmingham Civil Rights leaders and over 2000 people gathered to hear them speak. In his speech, Robinson condemned President Kennedy for not sending troops to quell the police violence and ensured the people of Birmingham, especially the youth, that the eyes of the world were on their city. He also spoke positively of the business leaders who had worked with Dr. King on the plan for desegregation. “The only thing we are asking,” he declared, “is that we be allowed to move ahead just like any other American.”

Jackie Robinson speaks at the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church, Birmingham, AL, May 13, 1963. Reuters

When the first rally was over, they departed to Pilgrim Baptist Church for a rally attended by hundreds of the youth protestors. Robinson focused his speech on how the children helped “awaken the conscience” of the United States as they marched and bravely took arrest. Patterson and Robinson would end the evening inspecting the damage to the Gaston Motel, where they would spend the night in an intact section of the motel.

Floyd Patterson and Jackie Robinson inspect bomb damage to the A. G. Gaston Motel, May 14, 1963. AP Images

Robinson and Patterson completed their trip to Birmingham with a visit to A.D. King’s home before returning to New York to participate in a rally held by the NAACP in Harlem.

For Robinson and the marchers, the Children’s Crusade was a major turning point in what many feared to be a stagnating Civil Rights Movement. In Birmingham, conditions began to improve. Jim Crow laws were repealed, albeit slowly, and Bull Connor, the police commissioner who led his department’s reign of terror, was swept out of office. Even so, the painful work of civil rights continued, both in Birmingham and around the country. For these children, many of whom are still alive and sharing their stories today, it was a moment of activation. They organized, stood together, and refused to back down, putting their own safety on the line to win desegregation in Alabama.

You would be forgiven if you thought the first Jackie Robinson Day was held on April 15, 2004, when Major League Baseball formally established the practice of honoring Jackie at ballparks across the country. Turns out, tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson inaugurated the celebration almost 77 years ago.

On September 23, 1947, at the end of Jackie Robinson’s debut season, Bill Robinson led the Ebbets Field faithful in an on-field celebration of baseball’s first Black superstar. Using donations solicited through the New York Amsterdam News, a local Black newspaper, Bojangles presented Jackie a new car, a television set, a gold watch, and even a fur coat for Rachel. For fans celebrating in the stands, in Brooklyn, and Harlem, the first Jackie Robinson Day was a way for New York’s Black communities to show their support for Robinson and the desegregation of Major League Baseball.

Jackie and Rachel Robinson are honored on the field in a pre-game ceremony on September 23, 1947. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Fifty years later, National League president Leonard S. Coleman, Jr. had the idea to permanently retire Robinson’s number from baseball, and on April 15, 1997, Major League Baseball honored the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Acting Commissioner Bud Selig, President Bill Clinton, and Rachel Robinson strode onto the field at Shea Stadium in the middle of the fifth inning of a game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the New York Mets. In an unprecedented move, the Commissioner announced that Jackie Robinson’s number 42 would be retired throughout the game of baseball.

Former National League president Leonard S. Coleman, Jr. reflects on the retirement of Jackie’s No. 42. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Robinson’s number now appears at every stadium alongside each team’s retired numbers. Coleman and many players around the majors wanted to find a way to continue to honor Robinson every year. In 2004, baseball made the Robinson celebration permanent by establishing Jackie Robinson Day on April 15. It was not until 2007 that players themselves began to push for many of the traditions we see today. It began with Ken Griffey Jr., who called Rachel Robinson and Commissioner Selig to ask if the number 42 could be temporarily reinstated so he could wear it that day to celebrate Robinson’s achievements. Soon after, other players made the request as well. Over 100 players, including four entire teams, took the field wearing number 42. A year later in 2008, the number of players increased to over 300.

The Chicago Cubs’ Derrek Lee (left) stands beside Ken Griffey Jr. (right) of the Cincinnati Reds on Jackie Robinson Day, 2007. AP Images

By 2009, the tradition of all players, managers, coaches, and umpires wearing Robinson’s 42 for Jackie Robinson Day became firmly established. As players line up on the foul lines at the beginning of each game at ballparks around the country, it is impossible not to notice the significance of Jackie Robinson and his impact on the game.

Ballplayers (and the United States as a whole) have come a long way since the eighties and nineties when many players had little idea of who Jackie Robinson was and what he accomplished. When Robinson was honored in 1997, African American players, both current and former, took it upon themselves to talk to the media, fans, and other players about the importance of Jackie Robinson. On Jackie Robinson Day, fans continue to show up to recognize Robinson’s importance to the fight for racial equality in the United States, just as the Flatbush Faithful filled Ebbets Field all those years ago.

The New York Mets celebrate a walk-off home run to win the game during the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees at Yankee Stadium on August 28, 2020. The day honoring Jackie Robinson, traditionally held on April 15, was rescheduled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sarah Stier, Getty Images

As we celebrate Jackie Robinson Day this year, it is important to remember that Robinson is being honored not merely because he was the first Black major leaguer in the modern era, but because he was a lifelong fighter for civil rights and economic justice. His life and work transcend baseball, both in our time and in his.

Though Jackie and Rachel Robinson were California natives, they became New Yorkers through their work, service, and deep investment in the city’s local communities.

When Jackie and Rachel Robinson moved from the McAlpin Hotel in Manhattan to an apartment in Brooklyn in the middle of 1947, they quickly sought to make the Flatbush neighborhood their new home. Jackie’s life as a public figure and role model for youth around the country was a busy one, even in the offseason. During his baseball career, Jackie found ways to become a part of New York’s civic and economic life—and draw a paycheck—when he wasn’t circling the bases at Ebbets Field.

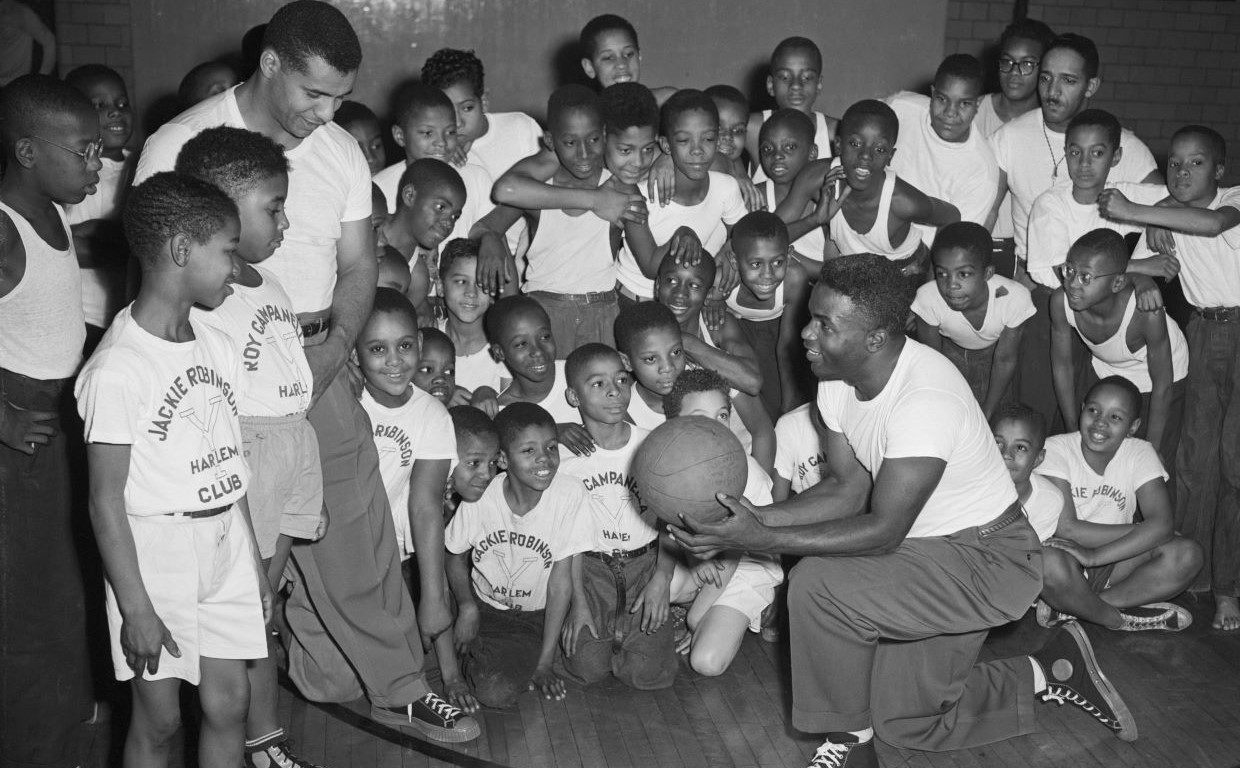

Jackie and Roy Campanella coach basketball at the Harlem YMCA, 1948. Courtesy of Getty Images

Robinson’s first and longest-lasting foray into community work began in the offseason in 1948, when he and Roy Campanella signed up to be youth coaches at the Harlem branch of the YMCA. For Robinson, this was a familiar way to show support for the Black communities in the city. After leaving UCLA, Robinson was a youth coach with the National Youth Administration in California, and he coached basketball in Texas as well. Although the pay was minimal, it allowed Robinson to live out his closely held belief that children’s access to sports and recreation were key to their social and mental development.

Sugar Ray Robinson purchases a TV from Jackie Robinson at Sunset Appliance, Rego Park, Queens, NY, 1949.

In the middle of the 1949 season, Jackie, Rachel, and Jackie Jr. moved further east, to St. Albans, Queens. Other Black celebrities had moved to the area as well in the 1940s, and Jackie and the family were excited to build connections in a new neighborhood. At the end of the season, Jackie took on a new job in nearby Rego Park as a TV salesman. Though Robinson’s short-lived stint at the Sunset Appliance Store might have been a publicity stunt to draw sports fans into the store, he handled the job with aplomb, signing baseballs for kids and chatting with adults as he made sales.

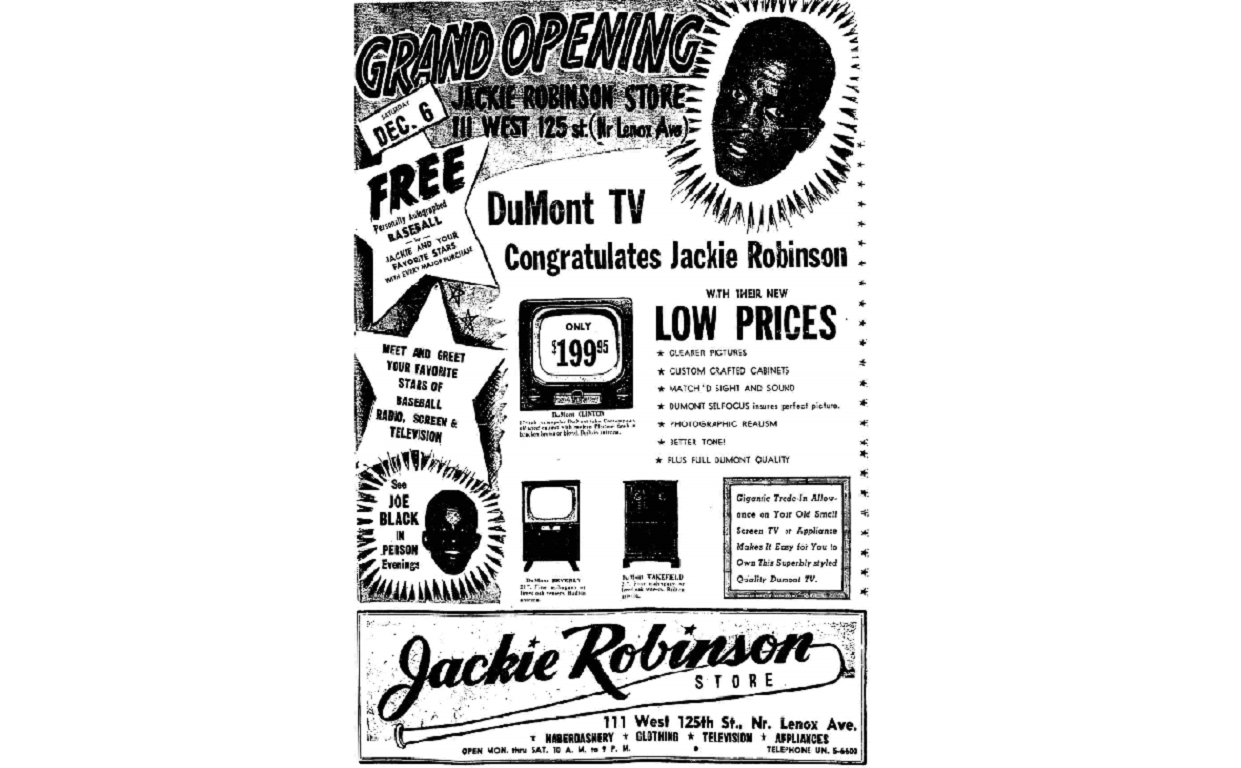

Robinson’s most ambitious business venture to date was the Jackie Robinson Store, which opened on 125th Street in Harlem in 1952. Robinson, who owned a 25% stake in the operation, wanted to open a department store offering high-quality goods to a Black consumer base that was often mistreated in Midtown department stores. Despite his sales experience, Robinson had limited knowledge about running a retail establishment and the store struggled to turn a profit.

An advertisement for the grand opening of the Jackie Robinson Store published December 6, 1952, in the New York Amsterdam News, Harlem’s Black newspaper.

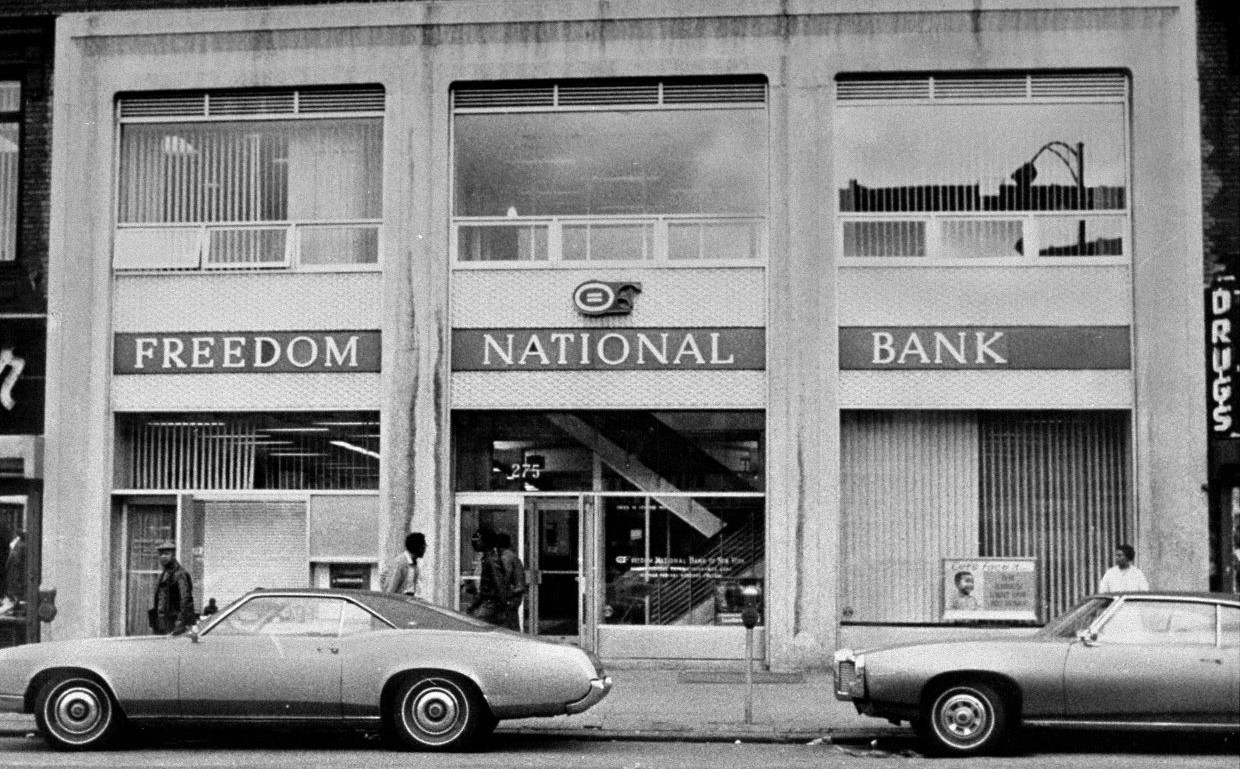

There were other difficulties as well. Because the store was mostly owned by Jackie’s white business partners, many Harlemites doubted that the store was keeping money in the neighborhood. Throughout Robinson’s tenure as a partner, he was forced to answer questions about whether he was merely a “front” for other white owners. Decades of job discrimination and economic disempowerment had left the neighborhood’s Black working-class residents with little to spend, further weakening the store’s bottom line. To improve the fortunes of Harlem, Robinson discovered, would require dignified places to make money as well as spend it. Despite these challenges, Robinson remained committed to bringing business opportunities to Harlem. Later, in 1964, Robinson co-founded Freedom National Bank, a lending institution that could help Black borrowers who might otherwise be frozen out of the financial system obtain mortgages and loans. While it succeeded in expanding many New Yorkers’ access to credit, it was often dogged by many of the same issues and criticisms the store faced a decade earlier.

Exterior view of Freedom National Bank on 125th Street in Harlem, ca. 1975. Courtesy of Getty Images

Jackie continued to invest in the city for the remainder of his life. In addition to writing syndicated newspaper columns in the New York Post and the New York Amsterdam News, Robinson served as a vice president of the Chock Full o’Nuts coffee chain and stepped up among the city’s civil rights activists, debating Malcolm X and using his column to weigh in on issues like school segregation, youth employment, and housing. Over his life, Robinson built connections with businesses and community organizations that left his mark on the urban fabric. Though not all of his ventures were successful, Robinson was committed to using his celebrity and insights to contribute what he could to New York City.

Throughout the 1960s, Jackie Robinson and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. maintained a close friendship that was bound by their shared commitment to the Civil Rights Movement. Beginning in 1962 and ending with King’s assassination, the men collaborated as activists and organizers advancing the fight for political and economic equality for Black Americans.

Robinson’s closest collaboration with Dr. King began in 1962, though the two had corresponded for many years prior. When Robinson was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King’s grassroots activist organization, held a testimonial dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City in Robinson’s honor. Dignitaries such as New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller were in attendance, and Robinson was presented with a plaque by Wyatt Tee Walker, Executive Director of the SCLC and close ally of Martin Luther King. The dinner raised substantial funds to support the SCLC’s voting rights efforts, and it was key to strengthening the organization’s ties with Robinson’s celebrity power and the political connections it offered.

Jackie Robinson Hall of Fame Testimonial Dinner, The Waldorf Astoria, New York, New York, July 20, 1962

Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Despite the grandness of the occasion, King himself was unable to attend. He was in Albany, Georgia, where the Ku Klux Klan had burned three Black churches response to the SCLC’s involvement in voting rights efforts. Soon after the testimonial dinner, King implored Robinson to join him in Georgia to see the destruction for himself. When Robinson arrived, he spoke to parishioners and clergy, and vowed that the churches would be rebuilt. Soon after, King tapped Robinson to lead the fundraiser to do so.

Jackie Robinson and Wyatt Tee Walker inspect the remains of the Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Sasser, Georgia, September 9, 1962.

Bettmann Archive, Getty Images

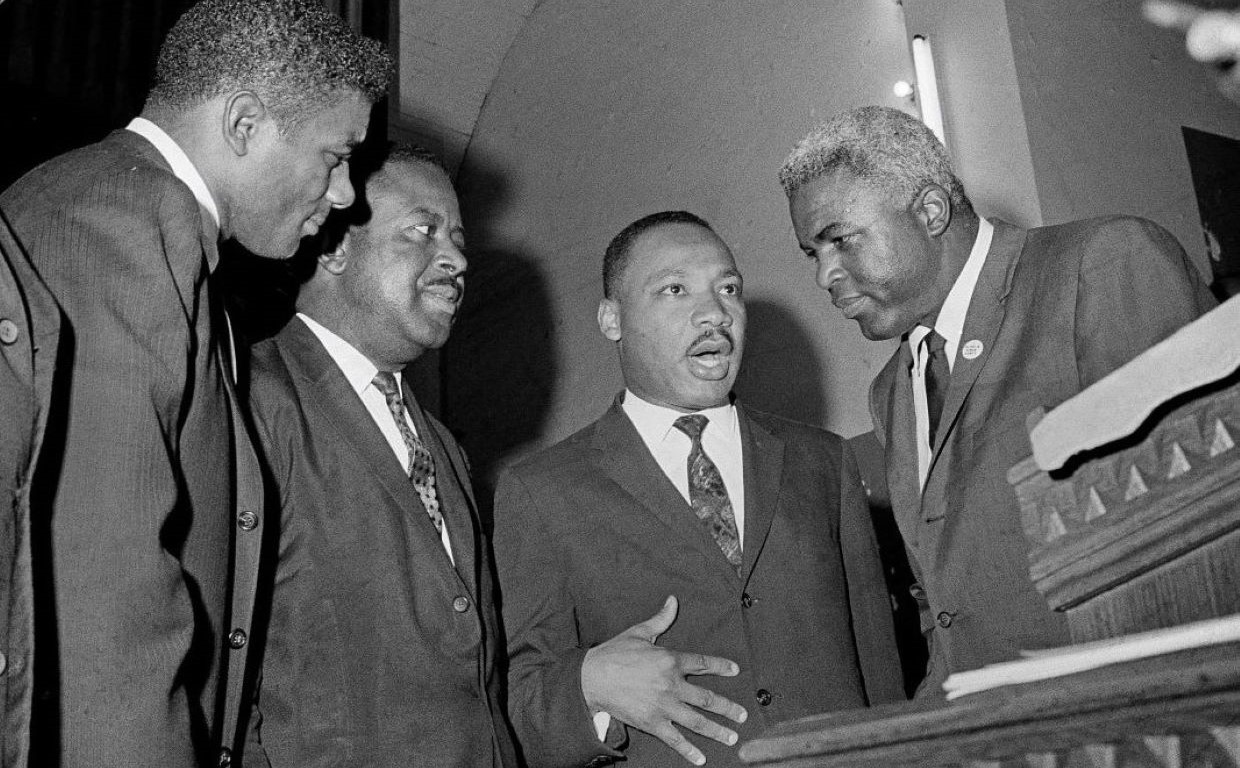

Robinson continued his work alongside King in 1963. On May 1st, the “Children’s Crusade,” a protest of youths marching against segregation in schools, was violently beaten back by Birmingham police. Ten days later, white supremacists bombed the home of Martin Luther King’s brother, and on May 13th, the Gaston Motel, which King used as his headquarters, was bombed in an assassination attempt. In response to this new wave of violence, Robinson launched the “Back Our Brothers” group, which brought together New Yorkers to raise money for King and his organizers. Soon after, Robinson returned to Birmingham accompanied by heavyweight boxer Floyd Patterson, to speak at a pair of rallies at the Sixth Street Baptist Church and Pilgrim Baptist Church. Robinson spoke alongside King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, criticizing President Kennedy for not sending the National Guard to defend the young protestors.

Floyd Patterson, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jackie Robinson at Sixth Street Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama, May 14, 1963.

AP Images

Robinson’s work with King continued through the summer. He hosted a Back Our Brothers fundraising dinner honoring King and other SCLC leaders. He attended the March on Washington in August, leading the Connecticut delegation, and hosted two jazz concert fundraisers for the SCLC’s efforts that year, one in June and one in September. The first raised over $15,000 for the SCLC. The second, which was a joint fundraiser for both the SCLC and the NAACP and was attended by both King and NAACP chairman Roy Wilkins.

Rachel and Jackie Robinson with Rev. Martin Luther King and Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP at the second Afternoon of Jazz concert, September 9, 1963.

Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

In 1964, he traveled with King to Frankfort, Kentucky and St. Augustine, Florida to lead marches for desegregation in public accommodations. Shortly after his Florida visit, Robinson and King made one more stop in Georgia to view the progress on the rebuilt churches. By June, Robinson’s fundraising operation had been a success. He had raised over $50,000, and the churches were almost complete. All three still stand today.

Jackie Robinson and Rev. Marthin Luther King, Jr., lead 10,000 demonstrators on a March to Kentucky’s State Capitol to demand an end to segregation, Frankfort, Kentucky, March 5, 1964.

Bill Strode, The Courier Journal

Although Jackie Robinson was a civil rights leader in his own right, it is important to note, he was a follower as well. A man of immense fame and popularity, he deferred to movement organizers like Dr. King for guidance on how to maximize his impact as an admired leader, speaker, and fundraiser. Robinson embraced the idea that “a life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” His collaboration with Martin Luther King Jr., demonstrated his will to place his vision and beliefs into action.

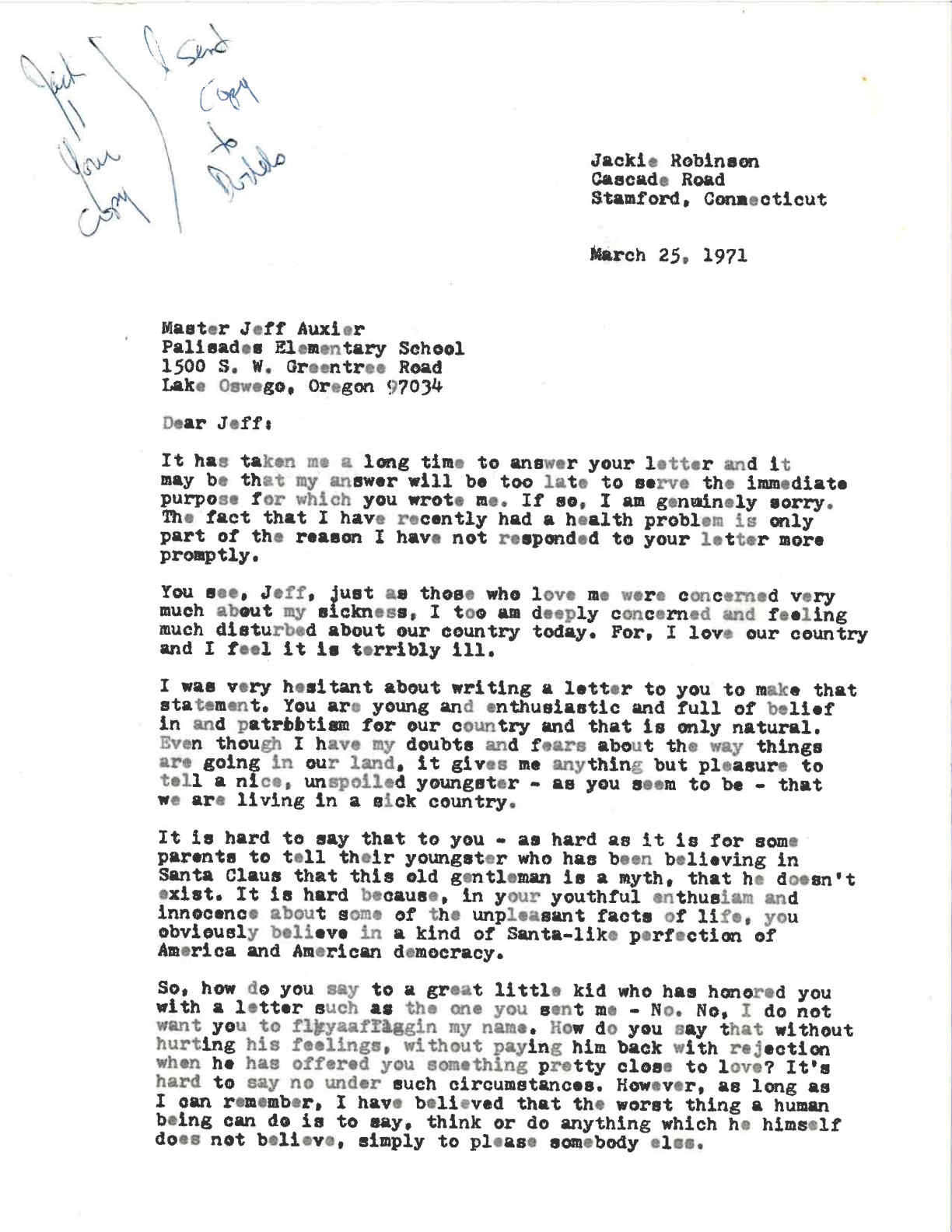

In early 1971, Jeff Auxier, a student at Palisades Elementary School, south of Portland, Oregon, sent Jackie Robinson a letter asking if Robinson would fly an enclosed American flag which was as part of a school project. Robinson responded with a lengthy and thorough letter, revealing the conscience of a ballplayer and civil rights stalwart who was disillusioned with the state of the country and was ready to pass the baton on to the next generation to continue the fight for civil rights and racial justice.

By March 25, when Jackie sent his response, his health was failing him. He had been hospitalized earlier that year and his vision was fading. In the opening to his reply, he apologized for his difficulties in getting back to Auxier, both in terms of how long it took to respond, and for the painful words that he needed to write. How would Robinson respond to a young child, full of patriotic hope for the United States, when Robinson himself knew that he had almost none left?

Copy of the first page of a letter by Jackie Robinson sent in response to a request to fly an American flag from elementary school student, Jeff Auxier, March 21, 1971. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Jackie knew what he had to say: No, Jackie Robinson would not fly an American flag at all. The country, he lamented, was “sick.” As the American war in Vietnam raged on and the civil rights progress of the previous decade had ground to a halt, Jackie Robinson no longer felt optimistic about the state of the country. For Jackie, this represented a profound shift from the patriotic rhetoric of his past. For many years, Robinson had believed that the highest ideals of American democracy could bring about the changes the Civil Rights Movement demanded. Even as other leaders made their cynicism toward American racism and injustice clear; Robinson had maintained his stance. By the late 1960s, after the assassinations of movement leaders Dr. Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers, that stance changed.

Throughout the letter, Robinson lamented how hard it was to tell these difficult truths to Jeff, but he recognized how important it is to do so. Over the course of Robinson’s life, youth empowerment was key to both his beliefs and actions. In the forties and fifties, he understood the profound impact that his baseball career could have on both Black and white children who saw him play. After his playing career was over, he made a phone call to the Little Rock Nine to show his support and led the Youth March on Washington for Integrated Schools. At his home in Stamford, Connecticut, he and Rachel would make sure to include their own children in the dinner-table conversations about their personal obligations to the Civil Rights Movement. To him, it was important that children and young adults be taken seriously, and that their opinions and ideas were treated with respect.

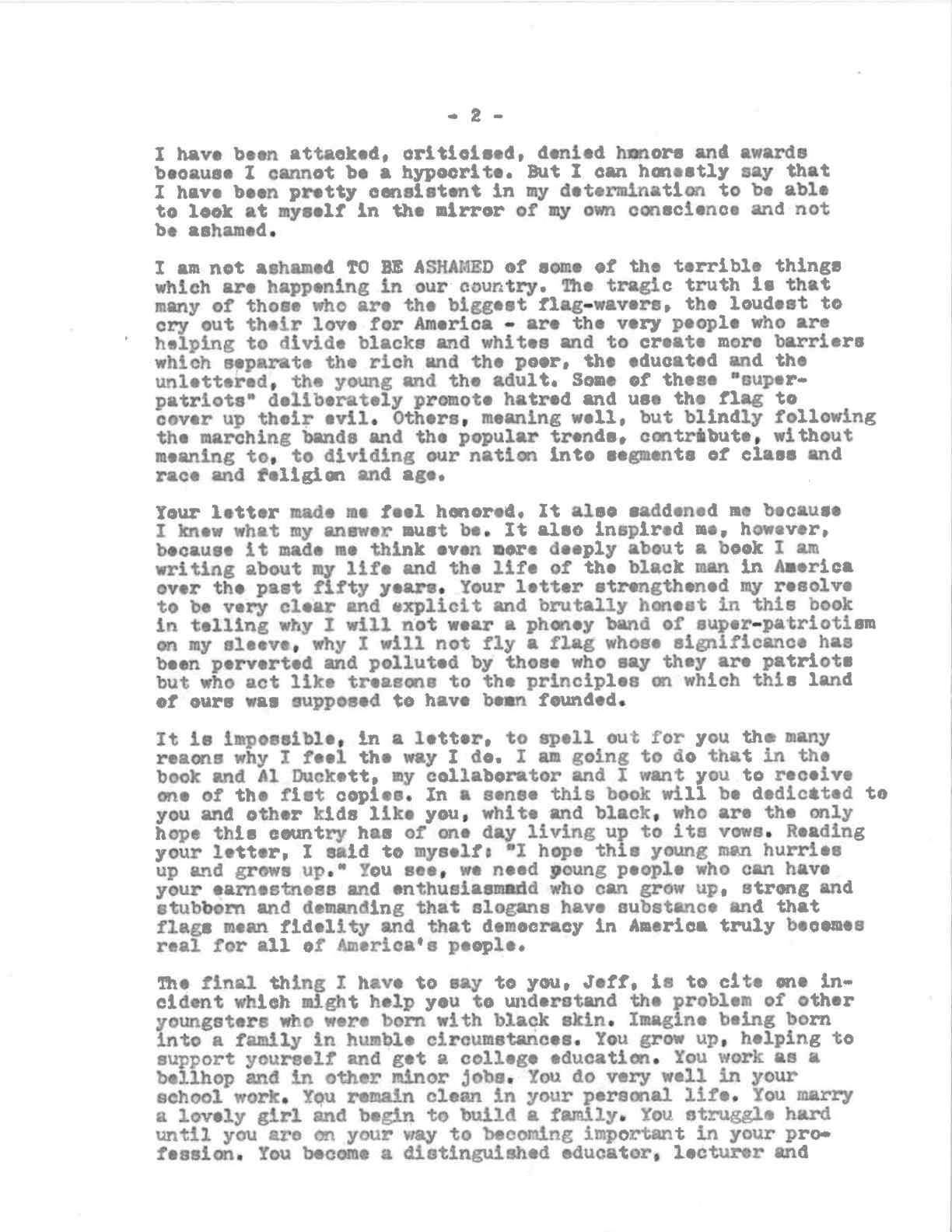

Page 2 of Robinson’s response to Jeff Auxier, March 21, 1971. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Later in the letter, Robinson noted that many of the things he wrote here would be reiterated in his upcoming autobiography, I Never Had It Made. The book, he said to Auxier, “will be dedicated to you and other kids like you, white and black, who are the only hope this country has of one day living up to its vows.” Jackie Robinson might have given up on empty symbols of nationalism, but he was not going to give up on the children who looked to him for encouragement and guidance. Even when the message he knew he had to deliver is not a hopeful one, he understood that his role as an elder was to provide inspiration to future generations.

Page 3 of Robinson’s response to Jeff Auxier, March 21, 1971. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Header image:

Jackie Robinson speaking to students at Joan of Arc Junior High School, January 9, 1962. Bettmann Archive, Getty Images

Every March, American and National League Teams descend on cities and towns in Florida to prepare for the baseball season and to determine which players will make their big-league squads and get in shape for the long season ahead. For Black players, spring training in the decades after integration put them squarely in the sights of Florida’s Jim Crow laws, where they were forced to navigate substandard accommodations, limited public transportation and other daily indignities.

Jackie Robinson with teammates at Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida, circa 1950. Getty Images.

By 1948, Jackie Robinson had largely been accepted in Flatbush as the first Black major leaguer, and many more Black players were working their way through the expansive system of Dodger farm clubs. But to have all the Dodgers train in Florida, decisions would need to be made to accommodate the growing roster of African American players.

The solution came in the form of abandoned Navy barracks in the town of Vero Beach. Branch Rickey and the Dodgers purchased it in 1948 and quickly christened it “Dodgertown.” As Black players joined the Dodgers and their minor-league affiliates, they would have a place to stay with the team as equals.

Images of Dodgertown, 1948-1955. Walter O'Malley Collection, Indian River Historical Society, Getty Images.

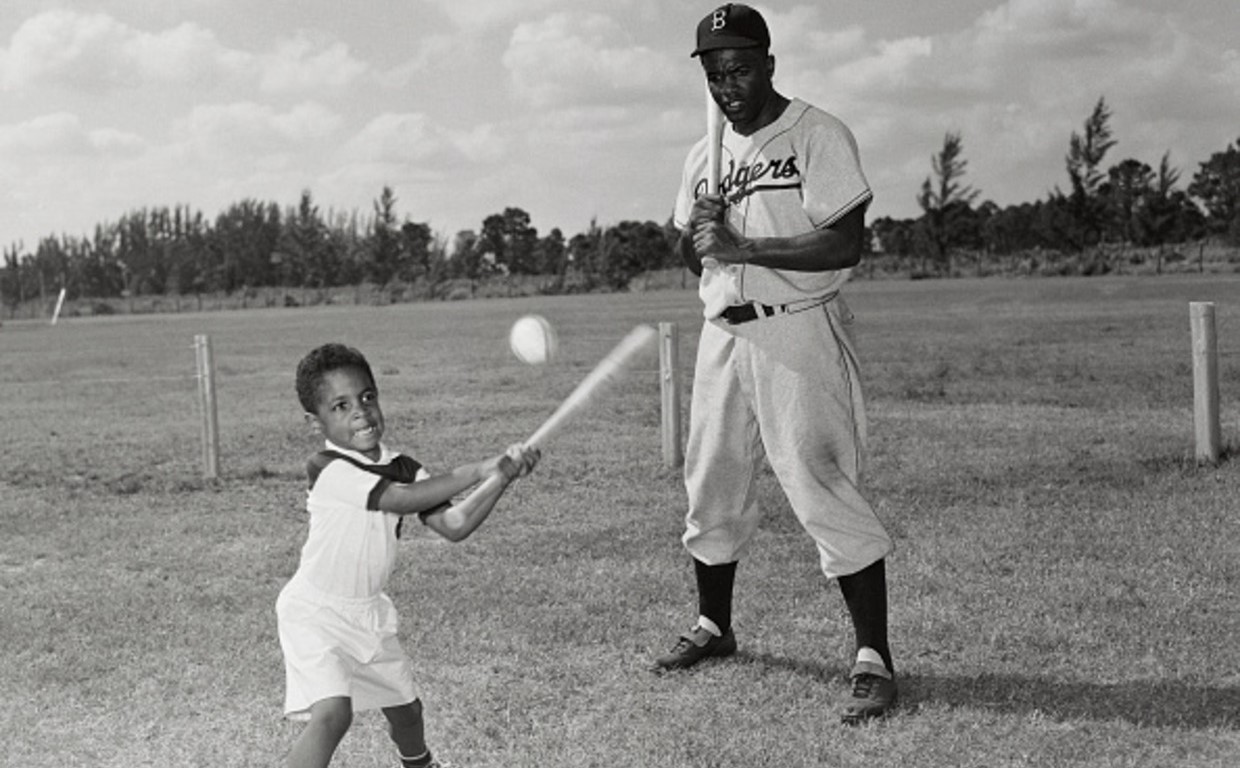

Compared to the difficulty of 1946, when Jackie Robinson and fellow Black player Johnny Wright stayed with a local family in Daytona, this was an improvement. Gone were the days of shuttling back and forth from distant neighborhoods to the ballpark. At Dodgertown, players and their families were able to eat in a well-appointed, integrated canteen on-site. Later, Dodgers ownership added a movie theater and a pitch-and-putt golf course as well, offering further opportunities for recreation for players. Jackie’s wife Rachel and toddler son Jackie Jr. were able to visit and spend time in the sun, away from both the cold northeastern winter and segregated Florida restaurants and hotels. Jackie Jr. would play on the fields, wave to fans in the stands, and drink fresh-squeezed orange juice.

Despite the care taken by the Dodgers to minimize the harm to their players from Florida’s Jim Crow laws, they were not protected when they left the base. In his autobiography, Jackie described how Rachel was unable to get her hair done in predominantly white Vero Beach. Not wanting to get lost on public transportation, she called a cab to take her and Jackie to a beauty shop in a Black neighborhood. The driver refused to serve her, telling her she needed to call a “colored cab.” Soon, she realized there was no such thing, and was forced to take a dilapidated bus across town.

Jackie Robinson and his son Jackie Jr. practice hitting at spring training at Dodgertown, 1949. Bettmann Archive, Getty Images.

Such humiliations were a part of the annual ritual of spring training in Vero Beach. After all, despite the improvements, Black players like Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and Jim Gilliam were limited to the amenities at Dodgertown or “Black only” venues offsite . Dodgers ownership even provided Gilliam with a car so that he could take other Black players to the nearby town of Gifford for off-base recreation.

(L to R) Unidentified, Roy Campanella, Herb Scharman, Barney Stein, Unidentified, and Joe Black after a day of fishing near Dodgertown, ca. 1952. Walter O’Malley Collection

The Dodgers remained in Vero Beach until 2008, when the team’s spring training headquarters moved to Arizona. For many team personnel, the move represented the end of a nostalgic era. Others, like Don Newcombe put it more bluntly. “I have no good memories of Vero,” he later said. For many Black players, Dodgertown represented both hope for the future of integration of baseball and despair at the realities of their segregated present.

After the 2008 move, the facility owned by the Indian River community was initially managed by minor league baseball, but in 2014 management was returned to former Dodgers’ owners Peter and Teri O’Malley and their partners Hideo Nomo and Chan Ho Park, both former Dodgers’ pitchers. In 2019, Major League Baseball took over operations and renamed the site the Jackie Robinson Training Complex, which plays host to a number of tournaments each year for young players looking for high levels of competition. The ball fields and batting cages have been put to new use –giving younger generations a chance to hone their skills on hallowed ground.

Resources:

Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York, Putnam, 1972)

Ross Newhan, “It Wasn’t the Happiest Camp for Everybody,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2008

Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Headed Way Off-Base,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2008

Ray McNulty, “Dodgertown Looks Great Worthy of Its Glorius Past,” Vero News, June 17, 2021

On June 16, 1964, Jackie Robinson visited St. Augustine, Florida at the urging of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). A crowd of 600 had gathered at St. Paul’s A.M.E. Church that evening to hear him deliver a speech that kicked off a month-long direct-action campaign targeting the city’s segregationist policies at local businesses, beaches, and swimming pools. He blasted his critics, especially those in the white press who admonished Black superstars for joining the movement. He told stories of how Willie Mays could not buy a home in San Francisco and how Nat King Cole was beaten in Birmingham for trying to perform in front of an integrated audience. “There is not one Negro, not one that I know of in this country, that has it made,” he declared, “until the most underprivileged Negro in St. Augustine, Florida has it made!” The crowd burst into applause.

Jackie Robinson Speaks at St. Paul's A.M.E. Church in St. Augustine, Florida. Courtesy of ABC News

Robinson understood that the sleepy tourist town of St. Augustine was of critical importance to national politics. Local leaders in St. Augustine had spearheaded a massive voter registration drive the year before, and with the November election looming, Robinson was keen on delivering those votes to the candidate that would provide the firmest support to future civil rights legislation, Democratic president Lyndon Johnson, in the upcoming November election.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was also working its way through Congress and St. Augustine was to host a celebration of the 400th anniversary of its founding a year later. With the spotlight already on the city, SCLC organizers and NAACP advisor Dr. Robert Hayling, the first African-American dentist to be elected to the local and national posts of the American Dental Association, were eager to use the media attention garnered by the upcoming celebration to their advantage as they led a month of rallies and marches. Robinson praised the protestors in his speech that evening, “You have taught me and I’m sure many people up north the kinds of accomplishments that can be made with the determination such as you have exhibited. I think the fact that people like this are willing to give up their freedom to go to jail is an indication exactly what they believe about America.”

The SCLC’s gambit worked: tourism in the summer of 1964 collapsed, forcing the hand of a remarkably conservative business community to endorse the creation of a biracial commission to combat racism in the city. The bravery of the marchers in Saint Augustine, combined with the national spotlight on the events unfolding there, helped keep civil rights at the forefront of American minds. The Civil Rights Act was signed into law less than three weeks later, banning segregation in public places.

While the protests in St. Augustine may have been a success in terms of publicizing civil rights pressure when it was most politically valuable, the on-the-ground results of the marches within the city itself were much less tangible. Businesses reluctantly integrated but found few Black customers after the sheer vitriol with which they had been previously refused. Establishments that were more public or reconciliatory about integration were met with pickets by an invigorated Ku Klux Klan. After Jackie and the SCLC left, local organizers felt abandoned by the national organization.

St. Augustine would not be Robinson’s last stop. His activism took him across the country where he spoke in churches, in auditoriums, and at protests. Just weeks after this speech, he wrote in his syndicated newspaper column “One wonders how we will ever be able to enforce the new Civil Rights Act when, so often, the fate of accused culprits is left in the hands of friends and neighbors who would rather uphold the doctrine of white supremacy than to discharge the demands of justice.” But Robinson remained undeterred, continuing to point to successful actions like St. Augustine and using his celebrity to bring the eyes of the world onto the Civil Rights Movement.

Resources

Civil Rights Library of St. Augustine, https://civilrights.flagler.edu/.

“Jackie Robinson Urges Action,” Daytona Beach News Journal, June 16, 1964

Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-65. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1998

David R. Colburn, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877-1980. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985

Robert W. Hartley, “A Long, Hot Summer: The St. Augustine Racial Disorders of 1964,” in St. Augustine, Florida, 1963-1964: Mass Protest and Racial Violence