News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREIn the early 1960s, Jackie Robinson aided Martin Luther King, Jr., and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement as they fought for desegregation and economic equality across the American South. Robinson—not a trained organizer, minister, or labor leader, but a renowned and outspoken athlete—added his voice to the struggle wherever and whenever he was asked. In May 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, was the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement. From May 2 to May 10, over 1000 children marched in the streets to end segregation, in what later became known as Birmingham’s Children’s Crusade. White supremacists responded to the protests by bombing two locations where movement leaders gathered on May 11.

As these events were unfolding, Robinson was spearheading the “Back Our Brothers,” fundraising campaign that sought to channel desperately needed resources from donors in the North to movement leaders on the ground in the South. He would host an organizing luncheon on May 7 in New York City that raised $8000 to directly support the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Birmingham. At the luncheon Robinson read a telegram he sent to President John F. Kennedy, advising, “The revolution that is taking place in this country cannot be squelched by police dogs or high-powered hoses.”

That week, as images of police violence were broadcast on televisions across the county, Robinson watched in horror. Close to eight hundred youth protestors were arrested by the Birmingham Police Department in an attempt to stop the marches. On the second day of the protest, the police blasted the children with fire hoses and attacked them with dogs, injuring many. This reinforced Robinson’s resolve to join the marchers in Birmingham and he began to plan his visit.

“Ex-Baseball Star to Join Big Protest,” May 8, 1963. The Associated Press Wire

On May 11, two days before Robinson went to Birmingham, white supremacists bombed the home of A.D. King, the brother of Martin Luther King, Jr., while the family sat in their living room. Like his brother, A.D. King was a politically active minister, which made him a target for the Ku Klux Klan and the local police. Later that night, another bomb was detonated at the A.G. Gaston Motel, where many civil rights leaders stayed when they visited Birmingham, causing widespread destruction.

In the midst of these aggressions, incremental progress was being made: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was nearing a desegregation agreement with Birmingham’s white civic leaders and businessmen, and the child protesters were being released from jail, where many had languished for over a week.

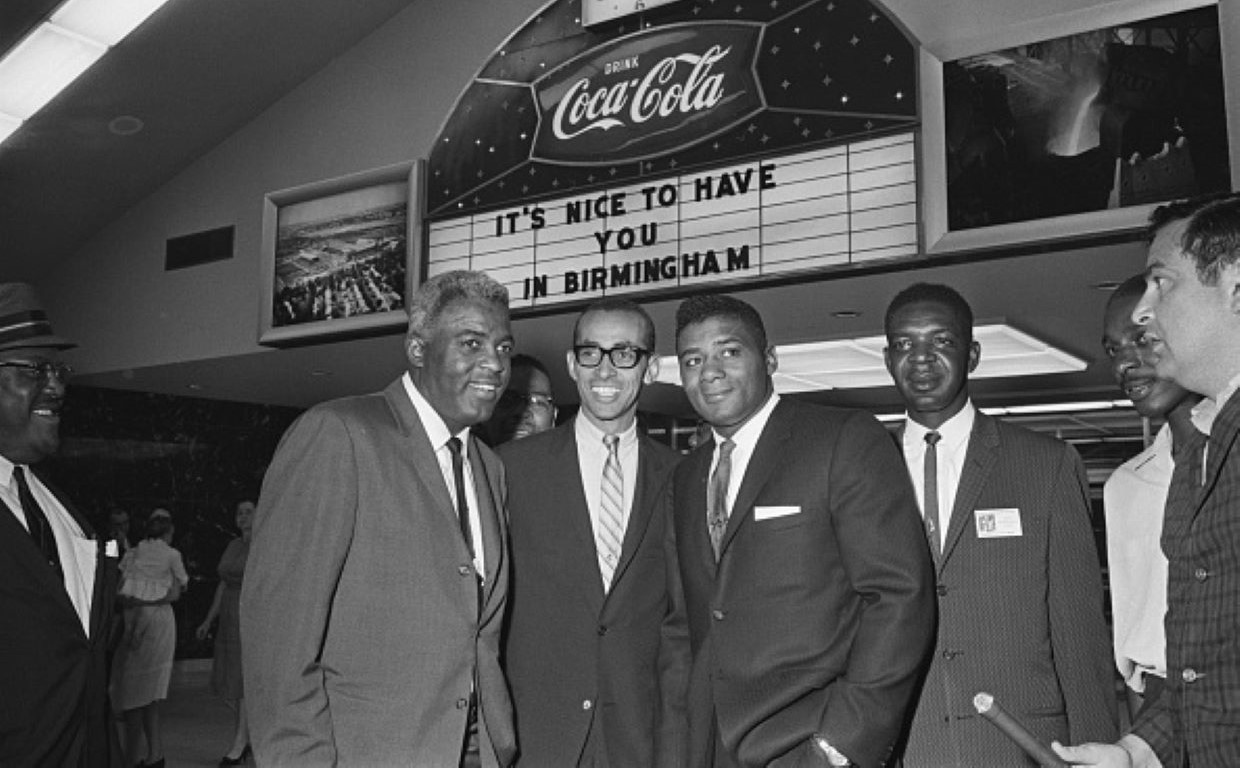

Jackie Robinson, Wyatt T. Walker, and Floyd Patterson at the Birmingham airport on their arrival late May 13, 1963. Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

On the evening of May 13, Robinson and boxer Floyd Patterson arrived in Birmingham to lend their assistance. They immediately drove to the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church where they were joined by Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and other Birmingham Civil Rights leaders and over 2000 people gathered to hear them speak. In his speech, Robinson condemned President Kennedy for not sending troops to quell the police violence and ensured the people of Birmingham, especially the youth, that the eyes of the world were on their city. He also spoke positively of the business leaders who had worked with Dr. King on the plan for desegregation. “The only thing we are asking,” he declared, “is that we be allowed to move ahead just like any other American.”

Jackie Robinson speaks at the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church, Birmingham, AL, May 13, 1963. Reuters

When the first rally was over, they departed to Pilgrim Baptist Church for a rally attended by hundreds of the youth protestors. Robinson focused his speech on how the children helped “awaken the conscience” of the United States as they marched and bravely took arrest. Patterson and Robinson would end the evening inspecting the damage to the Gaston Motel, where they would spend the night in an intact section of the motel.

Floyd Patterson and Jackie Robinson inspect bomb damage to the A. G. Gaston Motel, May 14, 1963. AP Images

Robinson and Patterson completed their trip to Birmingham with a visit to A.D. King’s home before returning to New York to participate in a rally held by the NAACP in Harlem.

For Robinson and the marchers, the Children’s Crusade was a major turning point in what many feared to be a stagnating Civil Rights Movement. In Birmingham, conditions began to improve. Jim Crow laws were repealed, albeit slowly, and Bull Connor, the police commissioner who led his department’s reign of terror, was swept out of office. Even so, the painful work of civil rights continued, both in Birmingham and around the country. For these children, many of whom are still alive and sharing their stories today, it was a moment of activation. They organized, stood together, and refused to back down, putting their own safety on the line to win desegregation in Alabama.

News

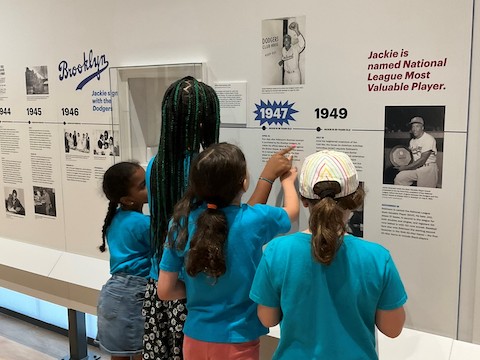

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE