News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Robinson’s Readers Story Time Kicks Off Dec 13!

At the beginning of the 1949 season, the Robinson family left their Flatbush apartment for a new home in the St. Albans neighborhood of Queens. In doing so, they joined a vibrant Black community in the Addisleigh Park section of the neighborhood. Throughout the forties and fifties, St. Albans was home to a wide range of Black musicians, actors, and athletes. Despite opposition from their white neighbors, and the neighborhood’s past as a segregated community, these entertainers and their families helped build a local legacy that still resonates today.

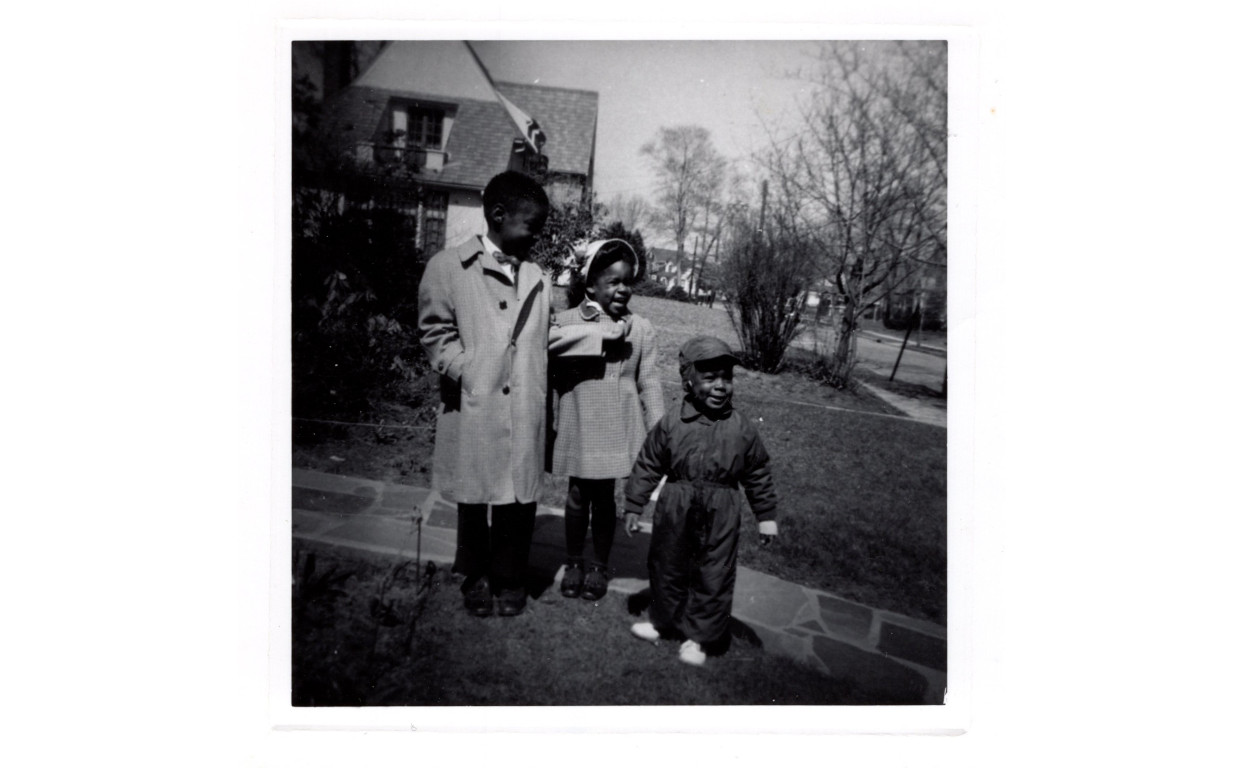

(l to r) Jackie Jr., Sharon, and David Robinson stand in front of the family home in St. Albans. Jackie Robinson Museum

By 1949, the Robinsons were realizing that their home, the second floor of a two-story house on Tilden Avenue in Flatbush, would soon be too small. Jackie Jr. was approaching his third birthday, and a second child, Sharon, was on the way. The family was looking for more space, which meant a move further from Ebbets Field than Jackie Robinson had lived since joining the Dodgers. In the middle of Jackie’s career-high 1949 season, Rachel found the family a new home, located at 112-40 177th street in the St. Albans neighborhood of eastern Queens.

112-40 117th Street, where the Robinsons lived from 1949 to 1954. Jackie Robinson Museum

Like many suburbs and neighborhoods in the Northeast, St. Albans carried a racist history. Planned as a railroad suburb in the early 1900s, the area quickly became home to hundreds of moderately well-off white families seeking to move outside of the city.1 While the area was not formally segregated when it was first developed, restrictive housing covenants were put in place in the 1930s and 40s, barring property owners from selling their home to anyone who wasn’t white.

A row of houses in Addisleigh Park in 2015. Wikimedia Commons

Covenants like these governed thousands of suburbs and neighborhoods throughout the early twentieth century. Crucially, these covenants were not formally laws: in 1917, the Supreme Court ruled in Buchanan v. Warley that zoning codes enforcing segregation were unconstitutional. Instead, these restrictions were written into the deeds of the properties themselves, declaring that they could not be sold or rented to Black people (or, in many cases, other racial and ethnic minorities). Generally, every property in a neighborhood or town would have such a clause written into the deed. In the 1930s, having such a covenant was often a requirement for receiving a mortgage backed by the Federal Housing Administration.

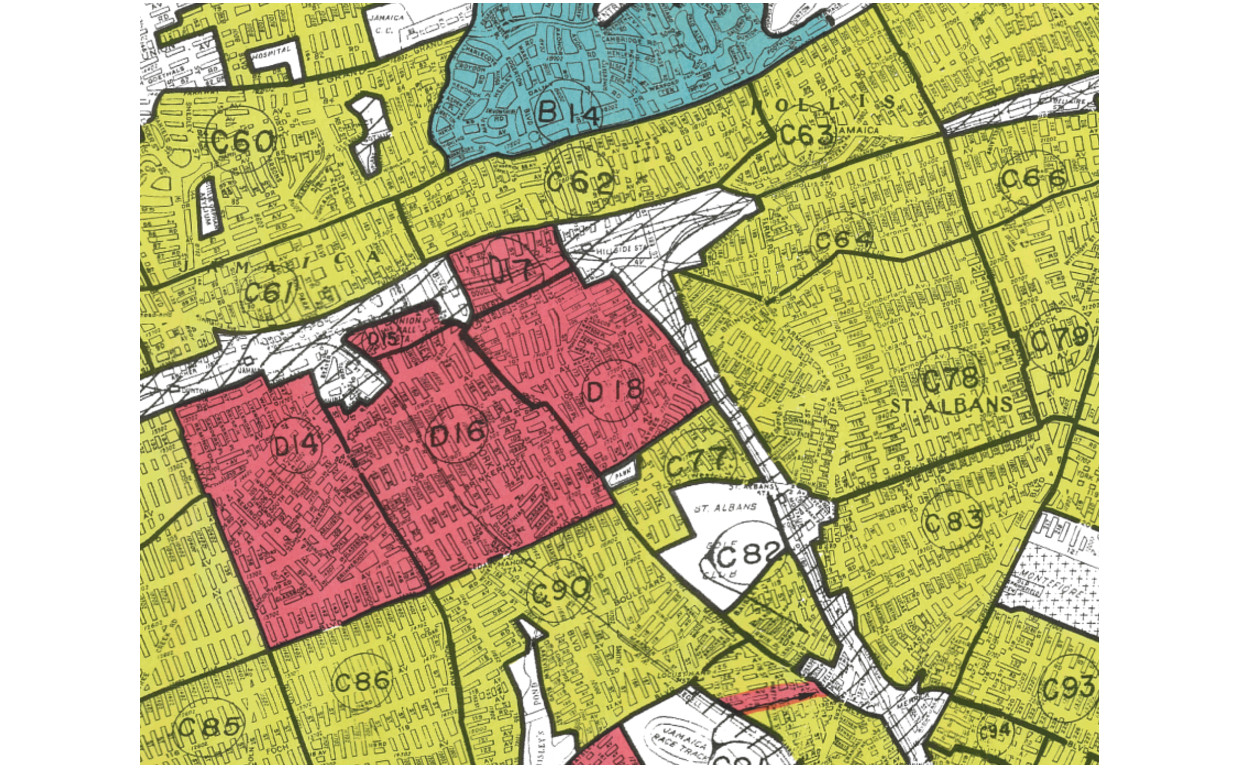

A redlining map of the St. Albans Area. Public Domain, courtesy of Mapping Inequality

Between 1935 and 1940, the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) produced a series of maps of every major American city, assigning labels to different neighborhoods based on how desirable they were to mortgage lenders. Areas with a sizeable Black population were given red labels, indicating that they were the least desirable for banks. This process came to be known as redlining. While these maps themselves were not necessarily used to determine whether an individual borrower would receive a loan, they reflect and codify racist practices that were already widely in use. Residents of red areas typically paid higher interest rates on mortgages—if banks were willing to lend to them at all.

The Robinsons moved into their home (located in the section labeled C77) in 1949, about a decade after HOLC produced these maps. According to the accompanying report, section C77 had a “gradual encroachment of Negroes from the north” (section D18), terminology suggesting that the creators of these maps regarded Black families both as economically undesirable and potentially dangerous to white homeowners. Further, the report noted that many other sections would have a downward “trend of desirability over the next 10-15 years,” reflecting the racial beliefs of both HOLC and other institutions who had designed similar maps in the twentieth century.2

In 1948, the Shelly v. Kraemer Supreme Court decision rendered racial covenants unenforceable, though redlining and other related practices continued. Even before then, a trickle of Black families had been moving to St. Albans as homeowners deliberately broke the covenants in their deeds. Other white residents fought back with lawsuits and racist leaflets.3 Refusing to welcome their new neighbors (and attempting to preserve their property values), many of them left. In their place, a larger wave of middle-class Black families began to arrive. Alongside them came a number of prominent entertainers. Beginning with jazz greats Count Basie and Fats Waller years earlier in 1940, musicians began to turn the area into a vibrant community. Other artists, athletes, and intellectuals followed soon after. Eventually, Ebony published an article (complete with the names and addresses of many famous residents!) boasting that St. Albans was “home for more celebrities than any other U.S. residential area.”4

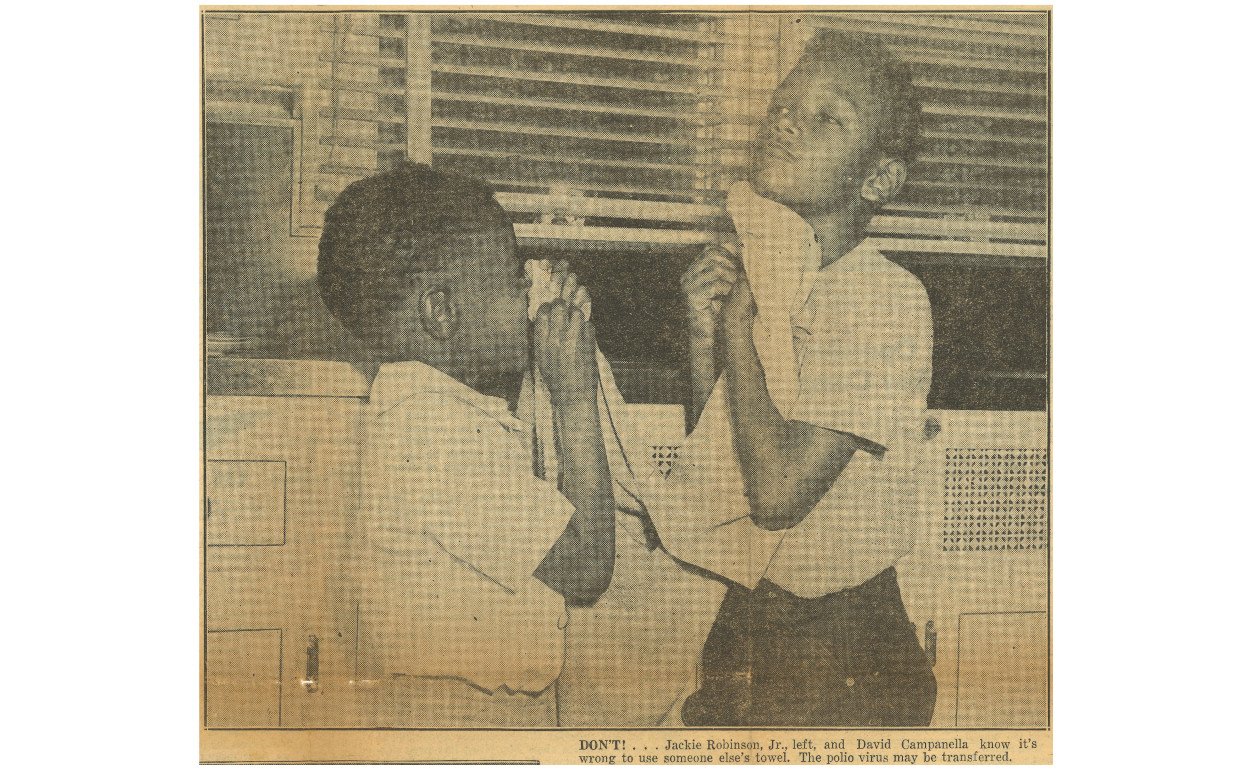

Friends Jackie Robinson Jr. and David Campanella demonstrate less-than-ideal towel use in a 1951 polio prevention public service announcement. New York Amsterdam News, Jackie Robinson Museum

Roy Campanella, Robinson’s Dodgers teammate, moved to St. Albans in 1948. After Jackie and the family arrived the next year, Jackie Jr. and David Campanella, Roy’s eldest son, became close friends, enjoying the community they shared in their new neighborhood. Though the family now lived miles away from Ebbets Field, privacy was still impossible. Jackie recounted how baseball fans would constantly swarm the house, taking pictures and demanding to see the children. “Usually, Rachel was diplomatic with the intruders,” Jackie later recounted. “But some of the liberties people took got on her nerves.”5

Between 1946 and 1955, the list of famous names grew. Actress Lena Horne was the next to arrive, and other jazz musicians such as Ella Fitzgerald and Illinois Jacquet followed shortly afterward. Later, saxophonist John Coltrane and funk rocker James Brown moved in the 1960s. Political theorist and activist W.E.B. DuBois also called St. Albans home, as did his wife, Shirley Graham DuBois, whose novels and musical works continue to shape our understanding of race in America today.

Rachel and Sharon Robinson pose for the camera on the sidewalk in front of their St. Albans home. Jackie Robinson Museum

Robinson and Campanella weren’t the only athletes in town, either. Heavyweight champ Joe Louis (who had collaborated with Robinson to desegregate the Army’s Officer Candidate School during World War II) moved in 1955. Floyd Patterson, also a heavyweight title holder, lived in St. Albans as well. Patterson and Robinson would work closely together in the 1960s, traveling together to speak at civil rights rallies and even attempting to start an ill-fated housing development.

The Robinsons left St. Albans in 1954. Searching for a retreat from their busy city life (and the too-friendly-by-half baseball fans that came along with it), the family moved again, this time to a new home in Stamford, Connecticut. The Robinsons’ St. Albans house still stands today, as do many of the original homes in Addisleigh Park. For Jackie Robinson and the family, the neighborhood was not just a symbol of a changing America, but a home in which they could share in the growing racial diversity that defines New York City. Though Jackie Robinson’s stay in the neighborhood was brief, he helped build its culture into a vibrant Black enclave at the edge of Queens.

[1] Theresa C. Noonan, “Addisleigh Park Historic District Designation Report” (New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, February 1, 2011). https://smedia.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/2405.pdf

[2] Nelson, Robert K., LaDale Winling, et al. “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.” Edited by Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers. American Panorama: An Atlas of United States History, 2023. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining.

[3] https://www.untappedcities.com/explore-queens-addisleigh-park-the-african-american-gold-coast-of-ny/

[4] “St. Alban’s,” Ebony, September 1951.

[5] Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 116

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE