News

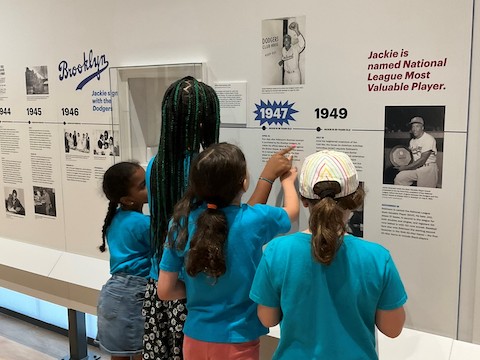

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Get your tickets for January Programs & Events!

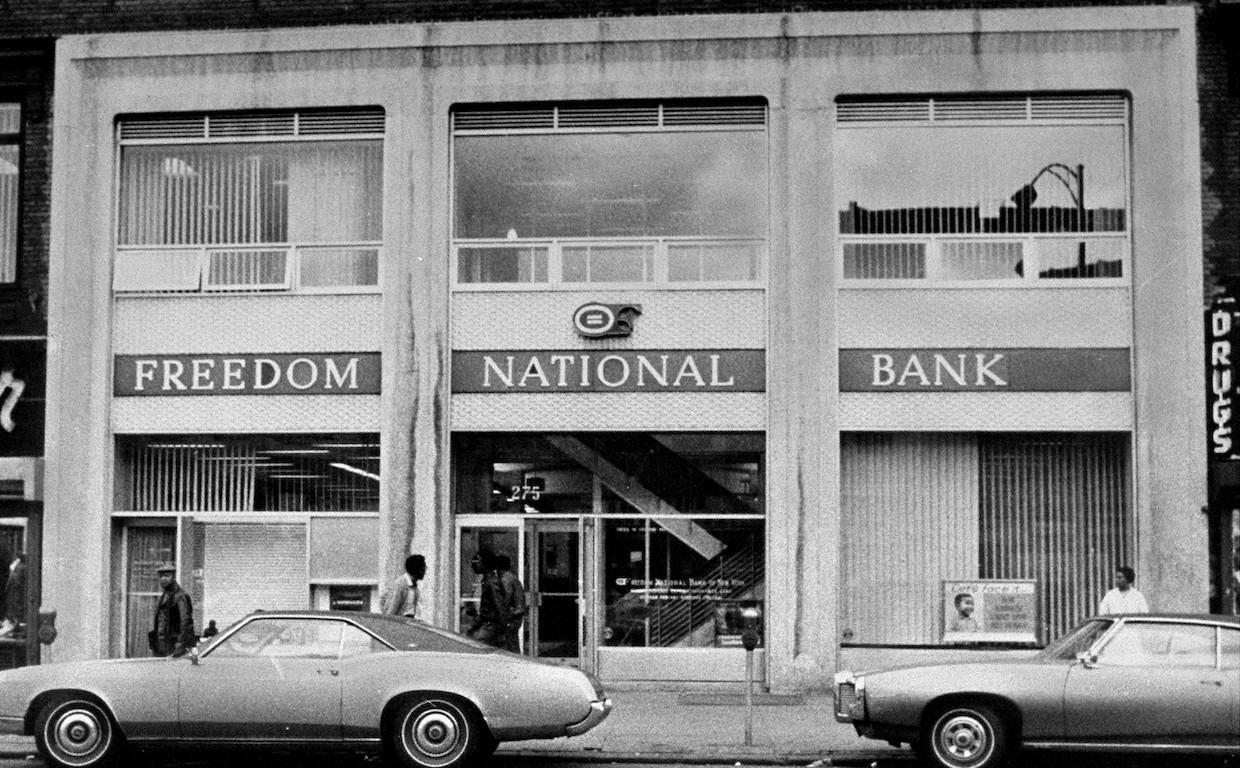

What can a bank mean to a neighborhood? To its depositors and borrowers, Freedom National Bank was a local financial institution not unlike thousands of others across the United States. But to many Black residents in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant, it was also a source of immense pride. From 1964 to its closure in 1990, Freedom National stood at the center of 125th Street in Harlem, providing access to banking services that many residents had previously been denied their entire lives. Jackie Robinson, who was the first chairman of its board of directors, worked tirelessly to ensure that its operations were not only a financial success, but that it was expanding access to loans and other services for Black communities across the city. Although the bank caused him incredible worry and many nights of lost sleep, it was a poignant example of his decades-long struggle for Black America’s economic progress and independence.

Main branch of Freedom National Bank on 125th Street in Harlem, 1970. Getty Images

In 1963, Dunbar McLaurin, a Black Harlem businessman, had begun to lay the groundwork for opening a bank in Harlem. He had dreamed of doing so for many years, but only by the peak of the Civil Rights Movement were his plans coming to fruition. It was a needed resource: African Americans had long struggled against banks refusing to loan to them due to economic dispossession as well as racist perceptions of Black borrowers as untrustworthy, inequities that continue to exist today. While means of discrimination have become more complex and technologized in the years since, McLaurin was confronting an issue that economists and activists are yet dealing with in the present: keeping money in New York’s Black communities.

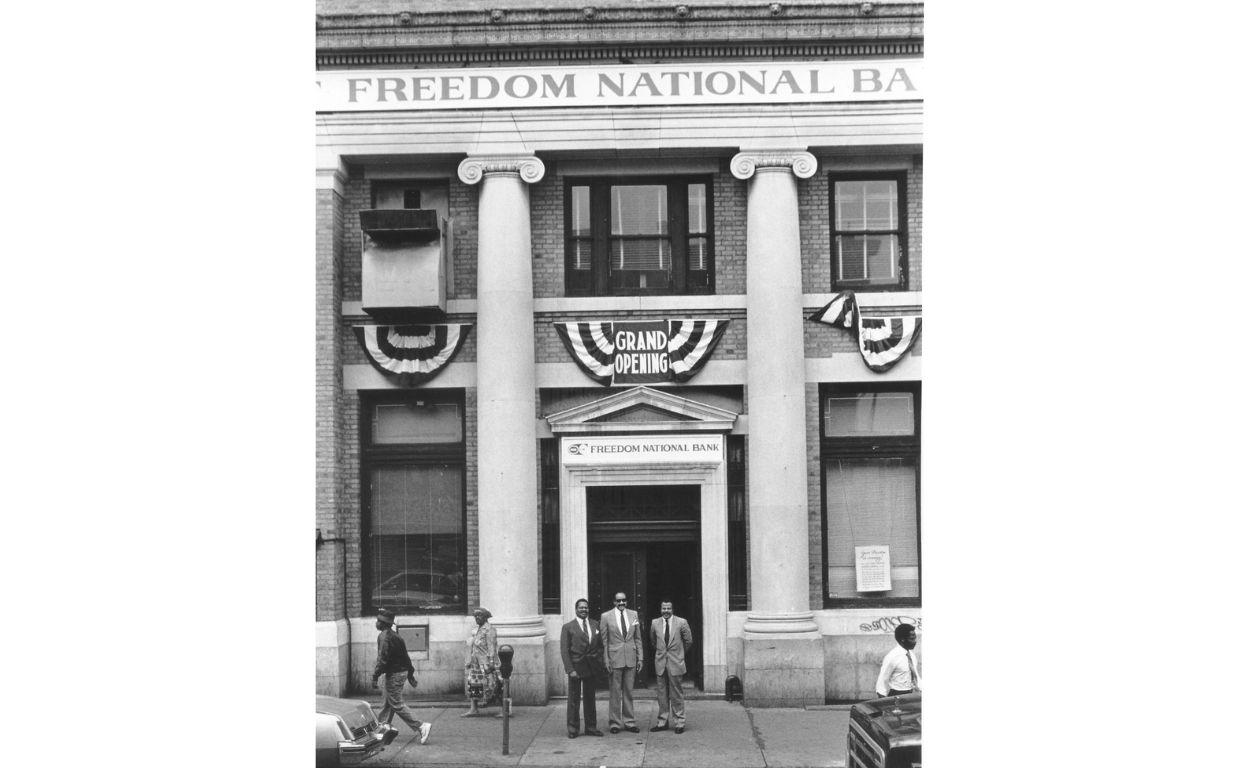

Jackie Robinson speaks to reporters at the grand opening of Freedom National Bank, WGBH.

Jackie Robinson was the ideal man to help McLaurin with the task. Robinson was a public figure with wide appeal and had developed significant business experience. Appreciating the importance of having a more equitable bank in Harlem, Robinson agreed to serve as chairman, if reluctantly. With regard to McLaurin’s role, Robinson and the other board members came to doubt his ability to run the bank and McLaurin’s bid to become the bank’s first president was rejected. McLaurin unsuccessfully sued the board, adding to delays in opening the bank.

Raising funds was likewise a challenge. When Robinson and his board made the first offering of 60,000 shares of stock available to the Harlem community, he was disappointed by the low level of interest, which he admitted was due to lack of trust. In search of a new president and dogged by the lawsuit, Freedom National Bank was not able to open until December 1964, with William Hudgins, an experienced banker from Carver Savings and Loan (another Black financial institution), as the new president.

The next January, Robinson celebrated the opening of the bank in his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News. “It is…the only bank in Harlem that is controlled mainly by Negroes,” he declared. At the grand opening, he noted how people coming and going from the ceremonies referred to it as “our bank,” reflecting residents’ recognition of its capabilities. Within a year, the bank had a capitalization of over $9 million. Hudgins took pride in his hands-on and meticulous approach to lending which allowed him and his staff to provide loans to businesses and homebuyers that might not even get in the door at other banks. Business boomed, and Freedom National was able to open a second branch on Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn in 1967, reflecting the growth of Black political and economic power there.

Freedom National Bank opened a branch office in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in 1967. Jackie Robinson Museum

Even so, the bank attracted criticism. Lack of financial stability and opportunities for employment for many of Harlem’s residents meant that many of the loans the bank made went to ventures outside of Harlem. Looking to attract more depositors, Hudgins often exaggerated the long-term impact of the bank on Harlem’s business environment. Despite these challenges, Robinson worked hard to make sure the bank could serve as many of its neighbors as possible. Rachel Robinson recalled how Freedom National occupied Robinson’s time and energy for years. “He agonized over that bank,” she noted in a later interview. “Anything that he thought was going wrong worried him because it was important for them to succeed.”

Rachel Robinson speaks on Jackie’s experiences at Freedom National Bank.

Indeed, the bank was an incredible source of stress for Jackie Robinson. Though he was in poor health for most of the late 1960s, he invested countless hours working to ensure its stability. When employees and regulators warned him about the possibility of the bank collapsing in 1971, he again stepped in to reorganize its leadership, replacing Hudgins as president while keeping him on the board. Eventually, the bank returned to stability and was able to continue its mission.

Mayor John Lindsay (right) speaks with Jackie Robinson at Freedom National Bank. Courtesy of the estate of Morris Warman

Robinson died in 1972, but the bank continued its operations for almost 18 years afterward. In 1982, booming business led Travers Bell, the leader of a Black-owned Wall Street brokerage, to purchase a large stake in Freedom. Despite Freedom National’s almost two decades of dutifully serving Black communities in Harlem and Brooklyn, Bell and his group pushed a strategy of rapid growth. The consequences were disastrous. Poorly collateralized loans made to larger and larger businesses, most of which were far afield of Harlem, led to massive losses as the tactics of the new leadership backfired. On November 9th, 1990, regulators shut Freedom down.

The loss of the bank hit Harlem hard. Residents bemoaned its demise and reflected on what it had meant to the community for years. Even more concerning than its closure, however, was the fact that many depositors were not compensated in full. In 1990, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, a New Deal-agency designed to protect consumers from bank failures, insured deposits of up to $100,000. While few individuals had accounts of this size at Freedom, a wide range of nonprofits and community organizations had large accounts there as a show of support for the bank’s mission. These depositors were only paid 50 cents on the dollar for money above the FDIC limit.

Ordinarily, this would not be unexpected. The limit, however, had rarely been observed in recent memory. Most failed banks were either taken over by nearby financial institutions or deemed “too big to fail” by regulators, who then bailed out all depositors regardless of the size of their accounts. For Freedom National, neither option was a possibility. Harlem residents were aghast at the FDIC’s inaction, and New York Congressional Representatives Chuck Schumer, Charles Rangel, and Major Owens held an emergency hearing decrying the unequal treatment of Freedom’s depositors. After the Representatives each delivered statements, community members echoed their condemnation of the FDIC’s capricious decision. Despite lengthy investigations into the matter, it does not appear that any of these organizations were made whole. A small bank in the middle of Harlem was not deemed important enough to receive the same treatment as a majority of other banks in that time period.

Jackie Robinson discusses Freedom National Bank in an interview with Dr. Lional Barrow and Tejumola Ologeboni, 1971, Courtesy of University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Libraries

Throughout its existence, Freedom National Bank brought services to Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant that had previously been denied to Black communities for decades. As Jackie Robinson often noted, “the ballot and the buck” were key to securing equality for Black America. Jackie had no experience in the world of finance but wanted to use his fame to support the fight for equality any way he could. He learned from others in the business, worked tirelessly to preserve the integrity of the bank, and collaborated with the employees to serve Harlem and Bed-Stuy. Though it lasted only a little over a quarter century, Freedom National Bank is still remembered today as a source of pride both during and after the years it stood on 125th street.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE