News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today!

Though Jackie Robinson traveled across the country to participate in the struggle for civil rights, one of his biggest contributions to the movement was close to home. So close, in fact, it was literally in his backyard. On the final Sunday in June 1963, Jackie, Rachel, and their children hosted their first “Afternoon of Jazz” concert on their lawn in Stamford, Connecticut, raising thousands of dollars for the cause. The concerts went on to become an annual tradition through which the Robinson family and their allies could express their love for great music and their commitment to equal opportunity.

The year 1963 was the culmination of a wave of changes that had been shaping the Civil Rights Movement since the Montgomery Bus Boycott almost a decade earlier. The battles were no longer being fought solely in courthouses and state legislatures; instead, people of all backgrounds were taking to the streets. These mass mobilizations across the South were drawing both international attention and violent repression, and leaders were growing fearful for the struggle’s continued growth. More critically, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s strategy of using mass civil disobedience to overwhelm local jails had created a new demand for bail money. The SCLC knew they needed cash, and they knew exactly who could help them get it.

Jackie, Rachel, Sharon, and David Robinson gather with musicians Herbie Mann (with flute) and Ben Tucker (with bass) at the family’s second Afternoon of Jazz in September 1963. Associated Press

Since his retirement from baseball, Jackie Robinson had emerged as one of the most effective fundraisers for civil rights organizations. He and Rachel were also great fans of jazz. With the help of longtime friend, activist, and singer Marian Logan, the Robinsons put together a star-studded lineup for a benefit concert.1 Dave Brubeck, Cannonball Adderley, Dizzy Gillespie, and others entertained a crowd of 500 assembled on the gently sloping hillside behind the Robinsons’ house. The performers contributed their time and talent for free, while the Robinson kids sold concessions and ushered guests. The $15,000 raised (about $150,000 in 2025 dollars) went directly to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

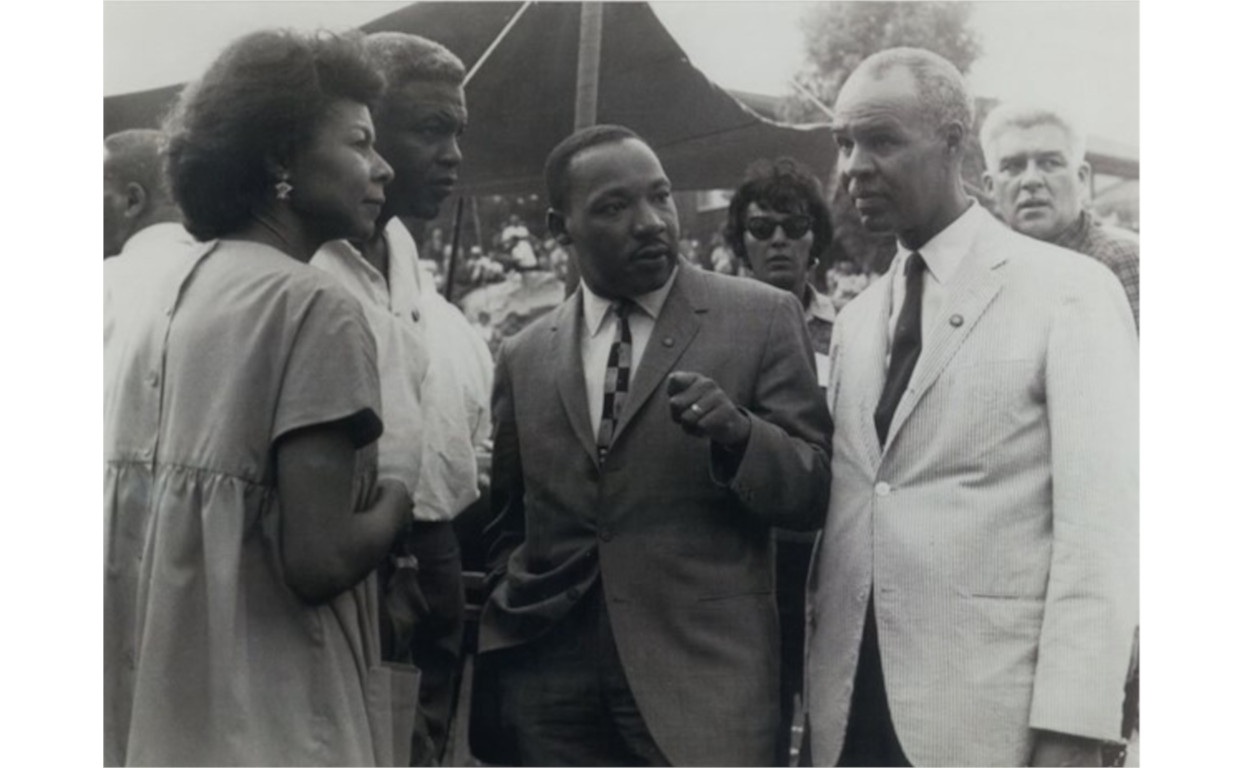

In 1963, soon after Jackie and the family returned from the March on Washington in the nation’s capital, the Robinsons held another concert on their lawn. Remarkably, the second iteration of the Afternoon of Jazz was even more successful than the first. This time, 1,300 turned out for a joint fundraiser for the SCLC and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. This time, Billy Taylor and Joe Williams headlined the show. Both Martin Luther King Jr., founder and president of the SCLC, and Roy Wilkins Jr., Executive Secretary of the NAACP, were able to attend.

Rachel and Jackie speak to Martin Luther King, Jr. (center right) and Roy Wilkins Jr. (right) at the second Afternoon of Jazz concert. Peter Simon, Jackie Robinson Museum

For Robinson, this was a unique triumph. These two civil rights organizations were vastly different in character: The NAACP, which has existed since 1909, had fought for progress in state legislatures and the courts for over five decades. The SCLC, on the other hand, dates back only to 1957. The group’s emphasis on nonviolent mass mobilizations had helped shape the popular character of the most recent phase of the movement, opening new terrains of struggle. While they shared some overlapping goals, the organizations used different tactics and often competed with each other for funds. Robinson’s concert created an opportunity for the two leaders (and their allies) to join together, allowing them to discuss strategy, rally supporters, and prepare for the battles ahead. The second concert captured the essence of the Robinson family’s emphasis on building the movement: To Jackie, it was not merely enough to be a famous voice that could write a big check. He wanted to bring people together using the tools at his disposal and encourage others, especially Black athletes and musicians, to show their support as well.

The first two Afternoons of Jazz passed with little fanfare. No live albums were recorded and no broadcasts were transmitted around the globe. No tell-all documentaries were filmed, and no jazz critics left prolix reviews of the concerts on the pages of national newspapers. The only major press that showed up was a LIFE photographer who contributed a short spread near the back of the next week’s issue.2 For Robinson and the performers, the money and the camaraderie were more than enough. Events like these helped build the movement when the demand for bail money couldn’t have been greater.

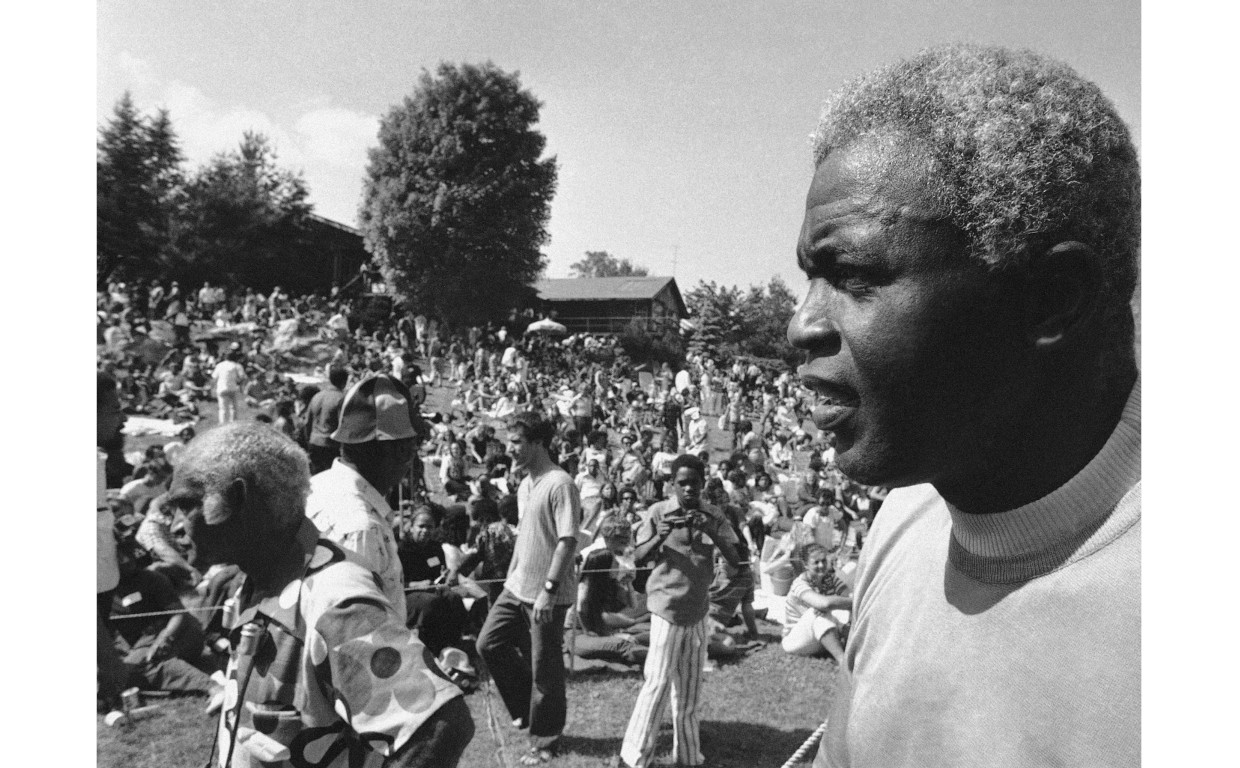

Jackie Robinson at the June 27, 1971 Afternoon of Jazz. This concert, largely organized by Jackie Jr., was a fundraiser for Daytop, a residential drug rehabilitation center where he served as a counselor. Tragically, Jackie Jr. was killed in a car accident ten days prior to the concert. The Robinson family decided that the concert would take place as planned to honor the memory of the man who worked tirelessly to put it together. Associated Press

As for the concerts themselves, they became an annual tradition for the Robinson family. The 1964 Afternoon of Jazz raised $27,000 to build a community center in Mississippi in honor of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three voting rights organizers murdered by white supremacists in June of that year.

Concertgoers gather for the 1980 edition of the Afternoon of Jazz. Jackie Robinson Foundation

For Robinson, the two 1963 concerts allowed him to continue to deepen his connections with the leaders that were building the ongoing Civil Rights Movement. They showed that his commitment to the cause went beyond public rallies and marches. Like his allies across the organizations with whom he collaborated, Robinson cared deeply about the inner workings of the movement and wanted desperately for it to succeed. Robinson’s contributions to the fight for civil rights cannot be fully measured in American dollars, nor would he wish them to be. Even so, as the jails began to fill and the future of the movement grew more dire, Jackie knew how much every cent could count.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

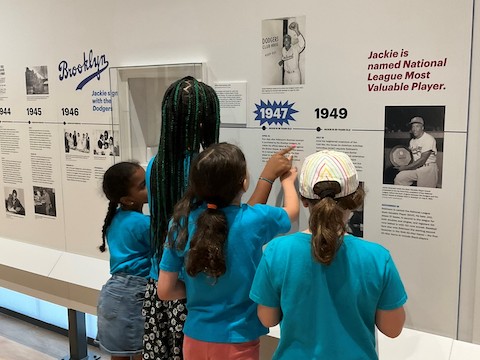

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE