Story Types: Jackie's Story

In the early 1960s, both Jackie Robinson and Malcolm X were towering figures in the struggle for racial justice in the United States. Though they were both active in Harlem during a time of tumult and political upheaval, they drew their support from different constituencies and often had sharply contrasting views on how the unfolding movement(s) should proceed. Though they met in person only briefly in 1962, they traded barbs and disagreements in newspaper columns, debating the stakes of the movement openly and in public. Robinson accused Malcolm of attention-seeking and poor leadership, while Malcolm criticized Robinson’s associations with white moderates who were often unresponsive or hostile to the demands of Black communities in cities across the country. Even so, the two were more aligned than either readily admitted. After Malcolm’s assassination in early 1965, Jackie wrote that the pair largely agreed on the severity of the issues facing Black Americans, even if their tactics diverged.

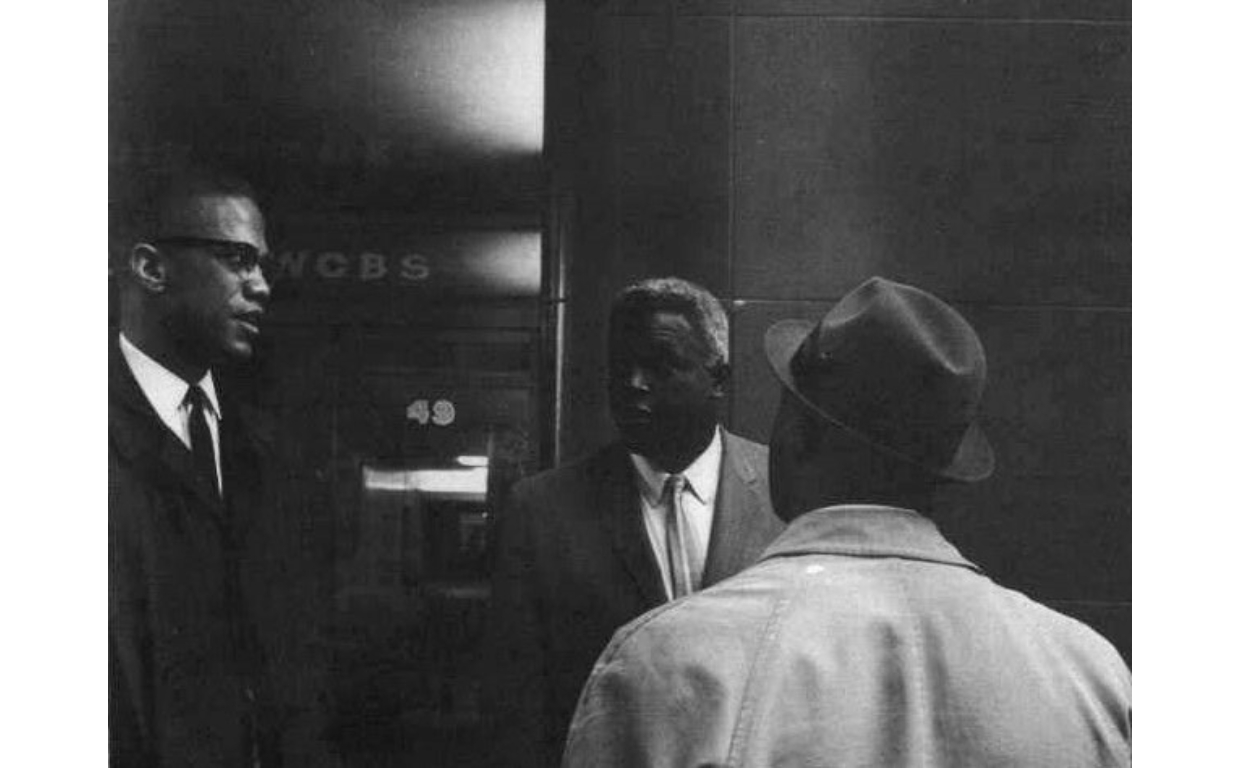

Malcolm X and Jackie Robinson at WWRL studios, July 1962. The New York Public Library

Malcolm, like Jackie, grew up far afield from the streets of Harlem. Born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1925, he moved with his family to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and then to Lansing, Michigan, while still a young boy. Malcolm’s parents, Earl and Louise Little, were hardworking and part of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). In 1930, after being forced out of the home they purchased in a white neighborhood in Lansing due to local segregation laws and sentiments, Malcolm’s parents bought a home outside of the city. Malcolm’s family continued to have frequent run-ins with local white supremacists, who deemed Malcolm’s father “uppity” and were believed to have been behind Earl Little’s early death in 1931, which was reported as a “streetcar accident.”

The challenges brought on by the death of Malcolm’s father likely led to Malcolm’s trouble with law enforcement. After being imprisoned in Boston on a burglary charge, Malcolm began his conversion to Islam. In 1952, he met Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, and began to establish new mosques across the United States, traveling thousands of miles to speak to congregations interested in the Nation of Islam’s teachings. As he did so, he brought a militant message to thousands of Black Americans who were growing cynical about desegregation and Christianity more broadly. As the Civil Rights Movement accelerated, especially in the South, Malcolm and his followers remained skeptical of the usefulness of working toward desegregation, instead developing a Black nationalist practice of self-reliance and self-defense tailored to the urban problems that many Nation of Islam members faced.

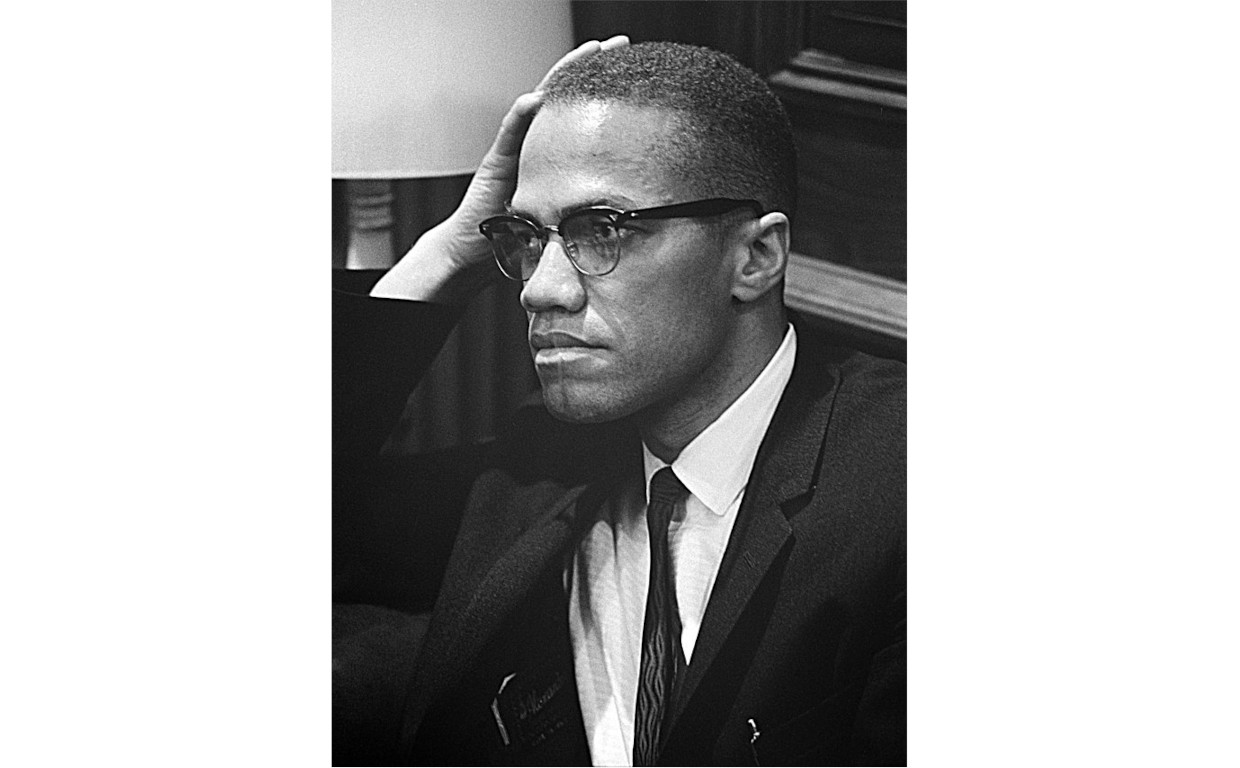

Malcolm X in 1964. Wikimedia Commons

In many ways, Robinson and Malcolm could not have been more different. Although both grew up in poverty, Robinson’s life and career in sports were marked by early successes in desegregation, through which Robinson was able to earn the acceptance (often begrudging) of at least some segments of white America. Malcolm, who was harassed by welfare officials, social workers, and the carceral state for much of his early life, acutely saw the limits of integration into a system that spared little dignity for Black people. As both influencers’ statures grew, they carved out different niches for themselves that were shaped by their personal experiences with race and injustice.

Malcolm X speaks in front of Harlem’s Hotel Theresa in 1963. United Press International

Robinson and Malcolm X first met in 1962, following a heated debate between Jackie and Lewis Michaux, a Black nationalist and bookstore owner in Harlem. What was ostensibly a protest against a new, white-owned steakhouse undercutting a nearby Black business had developed into an ugly series of pickets, with protesters chanting antisemitic slogans against the owners of the new restaurant. In his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News, Robinson excoriated the protestors, who were supporters of Michaux, advising them not to use bigoted language.1 Robinson engaged Michaux in a heated radio debate after which Michaux compelled the protestors to back off. Malcolm X, himself not a participant, was present at the studio where the debate was held, and spoke candidly with Robinson after.2

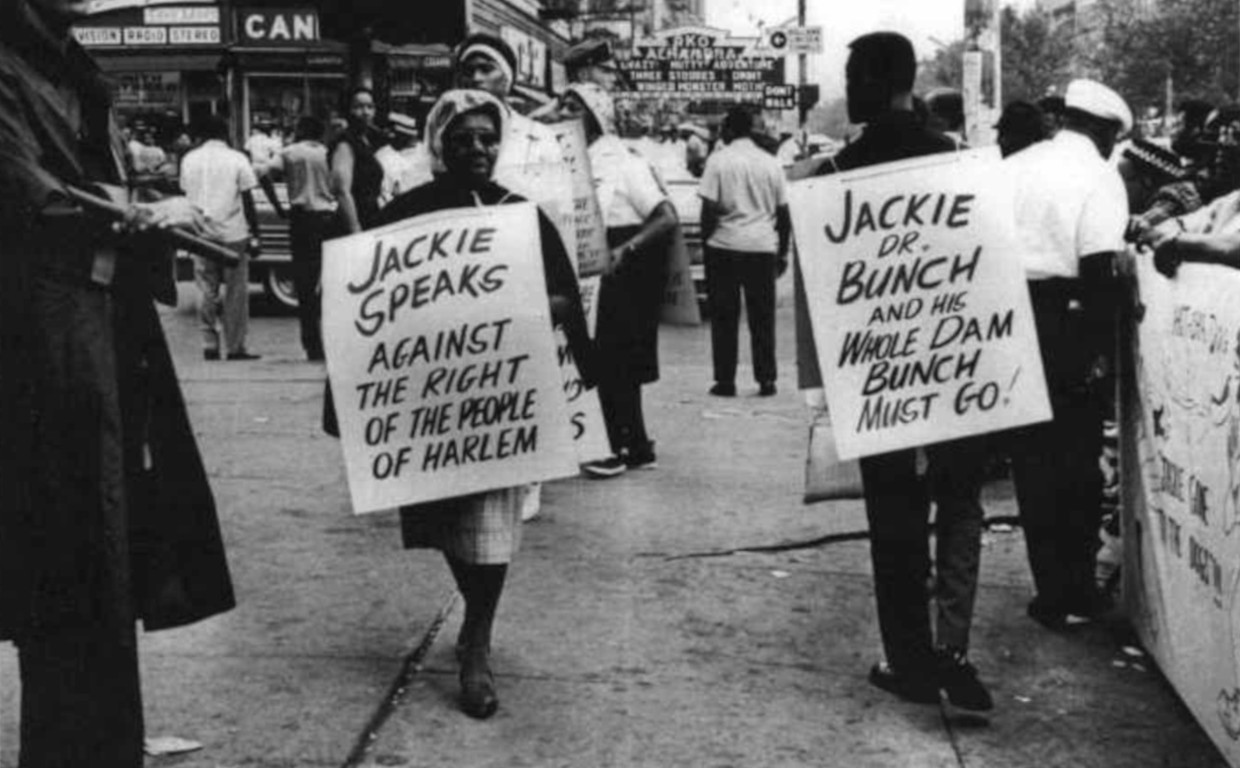

After Robinson denounced the protestors for using antisemitic slogans, Michaux’s group began to target the Chock full o’ Nuts in Harlem. Robinson, who was a vice president at Chock at the time, was specifically targeted. The New York Public Library

The next year, Robinson began to use his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News to establish a greater distinction between himself and the followers of Malcolm X. In July, after Martin Luther King’s car was targeted by Black nationalist egg-throwers in Harlem, Robinson accused Malcolm of leading the barrage, though Malcolm denied any involvement. “Malcolm has just as much right to be opposed to Dr. King as anyone else,” Robinson noted in the Amsterdam News.3 He even went a step further, suggesting that he himself didn’t agree with King’s philosophies: “I am not and don’t know how I could ever be non-violent. If anyone punches me…you can bet your bottom dollar that I will try to give him back as good as he sent.” Robinson, however, continued by noting that King and his integrationist allies represented the will of America’s Black population, rather than Malcolm X. He reiterated that it was “unfair” for King to be attacked this way, and even went as far as to suggest that Malcolm’s movement was being secretly funded by “important aid and sponsorship from outside the race.”4

Robinson continued his salvo that November, when he wrote in defense of Ralph Bunche, after Malcolm accused Bunche (then a well-known U.N. diplomat) of being a voiceless pawn of the American government.5 This column, though it focused primarily on similar attacks made by Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, resulted in a biting response from Malcolm, itself published in the pages of the News: “You became a great baseball player after your White Boss (Mr. Rickey) lifted you to the major leagues…bringing much money through the gates and into [Rickey’s] pockets,” Malcolm began.6 He then continued by outlining other points of disagreement with Robinson: Malcolm condemned Robinson’s 1949 testimony against Paul Robeson in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, as well as his close associations with Nelson Rockefeller and Richard Nixon, two Republican politicians who were not particularly well-liked by many Black New Yorkers. Finally, Malcolm cautioned Robinson that many of his white allies may someday turn on him and “be the first to put the bullet or the dagger in your back.”

Jackie Robinson poses with New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller in February 1966. When Rocky won re-election in November that year, he underperformed in Black neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Associated Press

Most of all, Malcolm X viewed many of Robinson’s actions as a betrayal. Writing in his autobiography in 1965, Malcolm recounted how closely he followed the early career of Jackie Robinson while he was in prison.7 A decade and a half later, however, he believed that Robinson had gone astray. Though the attacks were personal, Malcolm’s critique reflected the sentiment among some Black New Yorkers that Robinson had grown out of touch with the radical demands of the 1960s. Many Harlemites may have had the same questions about Robinson’s support for these politicians as Malcolm did, or had been hurt by Robinson’s testimony against Robeson years before. Robinson, already used to receiving hate mail of all sorts, received a deluge of letters criticizing his statements against Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell.8

In the broadest of senses, the conflict was a clash of politics and wills. Both sides drew new lines in the debate between integration and nationalism that has animated conversations around race since the arrival of the first slaves in the colonies that would become the United States. But it was also a conflict over strategy and tactics, shaped by the rapidly-crystalizing alliances that were forming in the movement. Robinson, for example, often merely accused Malcolm of being a figment of the white media, rather than a leader with a substantial following.9 Such a rhetorical flourish was almost certainly influenced by the politicking of some of his close allies: In 1961, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, on whose board of directors Robinson served, denounced the Nation of Islam as a hate group at its annual convention.10 Later, in 1966, NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins would go on to denounce Black Power more broadly, describing it as the “reverse” of Klan tactics in use in Mississippi.11

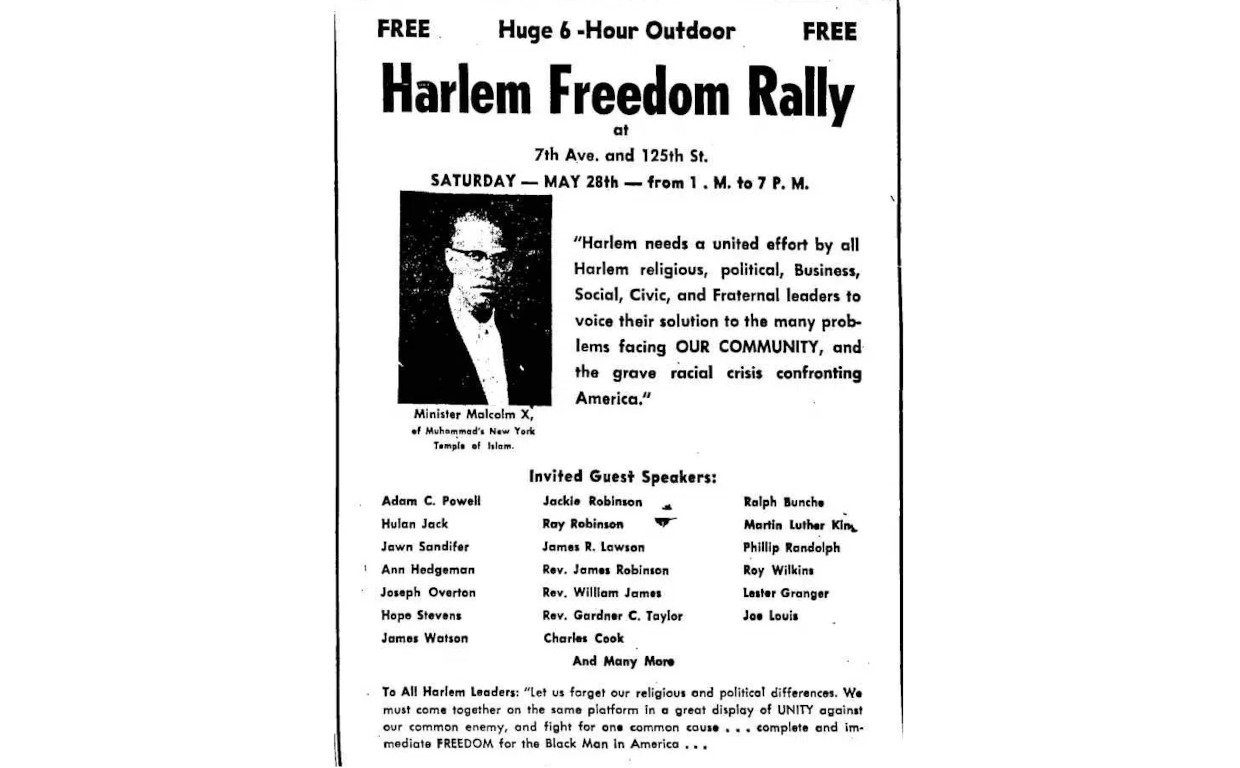

On May 28 1960, Malcolm X hosted a “freedom rally” in Harlem, to which a number of Black celebrities were invited. Robinson did not attend. New York Amsterdam News

Moreover, the conflict was borne out of the reality that neither fully understood how the other earned the support of everyday Black people across the country. Robinson did not yet at this time appreciate the importance of the work the Nation of Islam was able to accomplish around police brutality and accountability within major cities. Moreover, Robinson’s labeling of Malcolm as a firebrand devoid of ideology ignored the Nation’s attempts to ally with more “mainstream” organizations in the early part of the decade.12 Likewise, Malcolm X was generally unwilling to believe in Robinson’s ability to activate marchers and protestors in the cities and towns he visited across the South. By accusing Robinson of being a pawn of “white bosses,” he showed disinterest in the work Jackie had done to support the on-the-ground struggle, especially when it was stagnating locally or in need of money for bail. Both parties accused each other of leading the growing movement in the wrong direction, and said so sharply and openly.

It must be remembered, of course, that the conflict between Robinson and Malcolm X should not be interpreted as an intractable split between parts of the freedom struggle. As contemporary historians such as Timothy Tyson and Charles Cobb have noted, the line between “nonviolence” and “militancy” was often blurred, especially in the Southern states where the movement was being forged.13 Further, Robinson and Malcolm X had more than a few areas of agreement, including the need to fight for Black economic independence.

Robinson also shared Malcolm’s skepticism of Martin Luther King’s emphasis on nonviolence, though he was willing to put aside such tactical differences as he collaborated with King. An astute reader of the New York Amsterdam News would have had access to this debate in real time, and could use the words of the two thinkers to understand their own positionality within a rapidly-shifting political environment.

Jackie Robinson and Lewis Michaux shake hands following their 1962 debate. New York Public Library

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965 in the Audubon ballroom in Harlem. By then, he had distanced himself from the Nation of Islam and was increasingly being harassed by its members (as well as federal agents) prior to his murder. Upon his death, Robinson remarked that he rarely agreed with Malcolm’s prescriptions for the movement, though he affirmed that “many of the statements he made about the problems faced by the Negro people were nothing but the naked truth.”14 Mostly, Robinson admired Malcolm as someone who said what he believed, and did so plainly and forcefully, not unlike Robinson himself. The brief eulogy offered by Robinson in print was not one of reluctant acquiescence or false sentimentality. It was simply written out of respect for a man whose powerful voice would help define the struggle for racial equality for decades to come.

Robinson and Malcolm X had radically different visions for Black America in the 1960s. They operated within different channels of the movement and viewed each other with distrust, if not open contempt. Even so, the disagreement was productive: Their conflict, openly bared and syndicated on the pages of Black newspapers, allowed readers themselves to participate in the debates around integration and nationalism that were taking shape. The pair never got a chance to settle their differences. Both died at a fairly young age in the midst of an unfinished struggle for racial justice. Even so, the words they left behind continue to inform conversations about the Black American experience and the reality of disagreement within a mass movement.

To explore the relationship between Jackie Robinson, Malcolm X, and other prominent Harlem civil rights leaders, check out Jackie Robinson’s Harlem available for free online or as a walking tour.

References

- Jackie Robinson, “Strange Happenings On West 125th St.,” New York Amsterdam News, July 14, 1962.

- Lewis H. Michaux, “Cooperation And Unity: A Way Out: Peace, It’s Wonderful,” New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1962.

- Jackie Robinson, “Egg-Throwing And Dr. King,” New York Amsterdam News, July 13, 1963.

- Ibid.

- Jackie Robinson, “Malcolm X And Adam Powell,” New York Amsterdam News, November 16, 1963.

- Malcolm X, “Malcolm X’s Letter,” New York Amsterdam News, November 30, 1963.

- Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 126.

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1997), 381.

- Jackie Robinson, “Umpire Jackie Robinson Calls Errors He Sees–By Black and White,” New York Herald Tribune, April 26, 1964, Jackie Robinson Museum, see also: Jackie Robinson, “Mysterious Malcolm,” New York Amsterdam News, May 2, 1964.

- Garrett Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 93.

- Simon Hall, “The NAACP, Black Power, and the African American Freedom Struggle, 1966–1969,” The Historian 69, no. 1 (March 1, 2007): 58.

- Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say, Chapter 3

- See, for example Charles E. Cobb, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2015), and Timothy B. Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power, First Edition (Chapel Hill London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

- Jackie Robinson, “Some Warmth Is Gone,” The Chicago Defender, March 6, 1965.

On April 15, Jackie Robinson crossed the foul lines of Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field and took up his position at first base. As he did so, he became the first Black major league player since 1884, ending the secretive, league-wide “gentlemen’s agreement” among team owners to refrain from hiring Black ballplayers. It was Robinson’s first step in a ten-year major-league journey that would include a Most Valuable Player award, six National League pennants, and a World Series ring. But when Robinson stepped into the batter’s box and faced the dizzying curveballs of the Boston Braves’ Johnny Sain, he was just number 42, trying to make good on baseball’s biggest stage.

Robinson’s debut received a wide range of reactions in the press: The local white dailies in New York seemed largely indifferent, with some papers not even bothering to mention Robinson at all. In Black newspapers across the country, however, Robinson’s promotion to the Dodgers and first games in Brooklyn were front-page news as photographers and reporters celebrated his arrival and prognosticated about his future with the team. Robinson knew he was making history that day. He also understood that there would be a long road ahead.

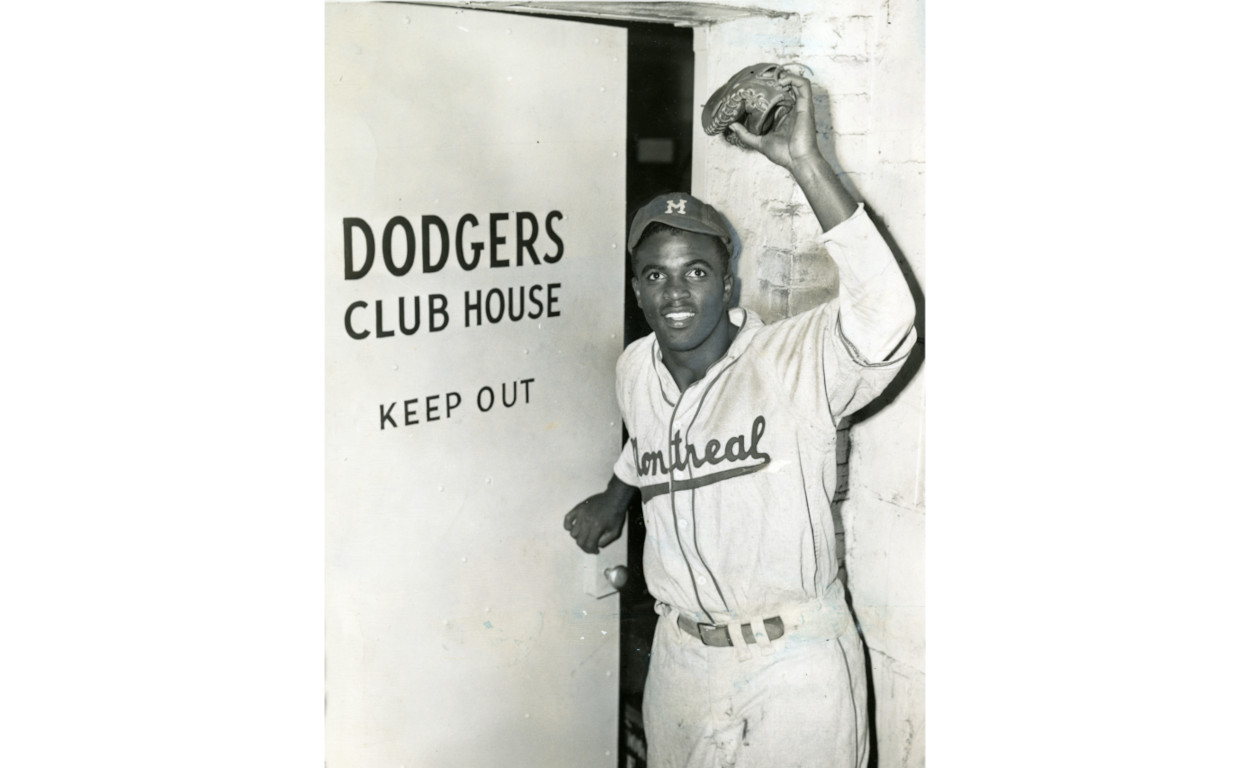

Jackie Robinson enters the Dodgers clubhouse on April 11, 1947 after the team purchased his contract from the Montreal Royals. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

By the final weeks of Spring Training in 1947, Jackie Robinson’s promotion from the Montreal Royals minor league squad to the Dodgers was not certain. Though he had a remarkable season in 1946, he had a difficult spring in Panama and Cuba, battling Jim Crow accommodations and stomach illnesses as he tried to make the team. As the teams headed north, Robinson still remained formally a member of the Montreal Royals.

Prior to Opening Day against Boston, the Dodgers played four exhibition games, one against their Royals farm club and three more against the Yankees. On April 10, the day of the first game, Robinson’s contract was formally purchased by the Dodgers, elevating him to the major league squad. The series drew almost 100,000 fans across the games, close to double the previous season’s exhibition total. “Robinson is the attraction,” declared Wendell Smith, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier and a close confidant of Jackie. “There is no doubt that Negro fans are showing their appreciation by digging down and coming up with money for tickets every day.”1 Even before the official start of the season, it was clear that Robinson would be a major draw.

Soon, it was time for Opening Day. As Jackie prepared for the game, his wife Rachel and infant son Jackie Jr. began their journey from their temporary home at the McAlpin Hotel in Herald Square to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Not wanting to get lost on the subway, Rachel tried in vain to hail a cab. Most turned her down. Whether it was because of the distance, Rachel and Jackie Jr.’s race, or some combination of both, she wasn’t sure. But eventually, she was able to get to the stadium in time to see Jackie play.

Rachel and Jackie Jr. join Ruth Campanella (left) at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947. Rachel enlisted the help of a hot dog vendor to warm Jackie Jr.’s bottle of milk. Jackie Robinson Museum

The Dodgers opened the 1947 season against the Boston Braves in front of a crowd of about 25,000 fans. Robinson batted second, between second baseman Eddie Stanky and center fielder Pete Reiser. Just as he did in the exhibition games, Robinson played first base that day, taking his position in the infield alongside Stanky, Dodger stalwart Pee Wee Reese at short, and fellow rookie Johnny “Spider” Jorgensen at third. First base was a new position for Robinson: He played primarily middle infield positions in college and with the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs, and spent most of the previous season in Montreal at second base. Even so, he performed exceptionally, going a perfect 11-for-11 in the field.

At the plate, though, Robinson was less successful. He was up against Boston’s Johnny Sain, a fiery curveballer who would go on to win 21 games that year. In his first trip, Robinson grounded to third for the second out of the first inning. In the bottom of the third inning, Robinson flew out to left, ending a 1-2-3 frame. In the fifth inning, with runners on the corners and one out, Robinson lashed a dribbler through the box that looked like it would be his first career hit and run batted in.2 Instead, Boston shortstop Dick Culler snagged the grounder, flipped it to the second baseman, who spun and threw to first, beating Robinson by a hair for an inning-ending double play.

Robinson faced Sain once more in the bottom of the seventh, with none out and the Dodgers down 2 to 3. After Eddie Stanky drew a walk, Robinson laid down a stellar sacrifice bunt, a scrappy move that would come to define Robinson’s style of play for a decade. A wild throw to first allowed Robinson to advance a base, and by the time the ball was returned to the infield, Stanky had checked in at third as well. Pete Reiser came to the plate next and immediately lashed a double to right, scoring both Robinson and Stanky and giving Dem Bums a 4–3 lead. Two batters later, Gene Hermanski scored Reiser with a sac fly, extending a lead that would be preserved for the rest of the game.

As far as debuts go, it was a far cry from Robinson’s four-hit, four-run performance in his first game in the minor leagues. Despite making history, Robinson barely made a splash in the white press: When New York’s sportswriter class sat down in front of their typewriters to summarize the game in the next morning’s dailies, Robinson was almost completely overshadowed by Reiser’s clutch hitting and the number of empty seats in the park that day. In Dick Young’s article in the April 16 New York Daily News, one of the city’s premier outlets for sports at the time, the historic import of Robinson’s debut wasn’t mentioned at all.3 Red Smith, of the New York Herald tribune, offered a summary of Robinson’s performance late in his article, but he, like Young, was far more interested in the suspension of Brooklyn’s popular manager, Leo Durocher, on account of his associations with known gamblers.4 In all, Robinson was mostly overlooked by these reporters, though given the immense pressure under which he was performing, he may not have paid it any heed.

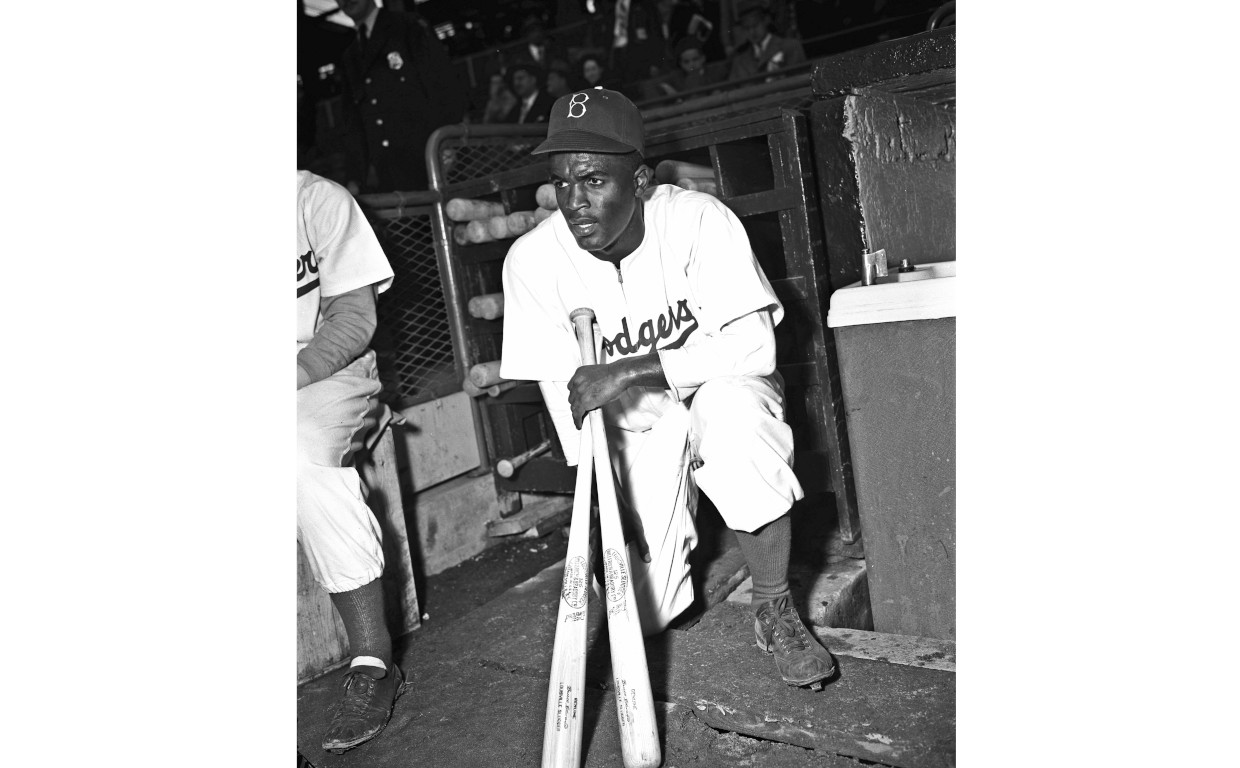

Jackie Robinson clutches a newspaper as he walks away from Ebbets Field after his April 15, 1947 debut. Getty Images

The response in the Black press was markedly different. Not only was Robinson covered extensively, his debut was front-page news in the Pittsburgh Courier, Baltimore Afro-American, and Chicago Defender. Because of the publication schedules of the Black weeklies (they typically published on Saturdays), Robinson’s debut was not covered until the April 26 editions of most papers, with the April 19 editions focusing primarily on the exhibition contests.

The delay didn’t dampen the effusive support. Large photo spreads highlighted Robinson’s actions before and after the game, and commentators offered predictions for the season and advice to fans. The Courier even ran a series of photos detailing the process of assembling the Robinson story for the newspapers’ readers.5 It is important to remember that Robinson’s debut itself was a triumph for the Black press: Wendell Smith of the Courier and Sam Lacy of the Afro-American played key roles in fighting for the desegregation of baseball. While the journalists and editors understood that Robinson’s (and Black America’s) fight against inequality and mistreatment in the twentieth century was still getting started, the pages of the weekly papers were a forum for communities to celebrate the progress that was being made.

Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier. Getty Images

The support wasn’t limited to the newspapers, either. Most sources reported that there were plenty of Black fans in the stands both during the exhibition series and the day of Jackie’s debut. The Sporting News estimated that 14,000 of the fans at the ballpark were Black.6 They made their voices heard too: Dixie Walker, a popular Dodger outfielder who had circulated a petition during the spring threatening to lead a strike if Robinson was promoted to the team, was greeted with a chorus of boos whenever he stepped to the plate. The support for Jackie persisted after the games as well. When Robinson left the stadium, he was mobbed by well-wishers, just as he was the year before as a breakout star in Montréal.

Back at home at the McAlpin in Manhattan, Robinson took his struggles at the plate that day in stride. “It was just another ballgame, and that’s the way they’re going to be,” he remarked to Ward Morehouse of the Sporting News.7 “I’m sticking to my style of playing ball…I like to meet the ball and hope a lot of them fall safe.” Robinson knew that Branch Rickey and the fans had faith in Robinson to make the grade as a major league ballplayer. There were 153 games left to play, and there was no point in dwelling on the first one.

Jackie Robinson observes the action on the field from the steps of the Dodgers’ dugout on April 15, 1947. Getty Images

Indeed, Robinson had a long way to go. Throughout his first season, he endured racist taunts, pitches thrown at his head, and opponents attempting to spike him on the basepaths. Despite the incredible adversity he faced, Robinson amassed a .297 batting average and lead the league in stolen bases and sacrifice hits. In September, he won the inaugural Rookie of the Year award, affirming his skill as a contact hitter and baserunner. Robinson could not have possibly imagined that his debut would be honored each year in ballparks across the country. Neither, it seems, did many of those who covered his first day in the major leagues. But for many of the fans in attendance, and the Black newspapers that followed his every move, history was being made that is still celebrated to this day.

References

- Wendell Smith, “Jackie Robinson Packing ’Em In: Dodgers Have Drawn 95,000 Fans in Four Exhibition Contests,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1947.

- “Robinson Swats First Home Run; Batting Average in Majors. 429,” New Journal and Guide, April 26, 1947,

- Dick Young, “Dodgers Nip Braves, 5-3, On Reiser’s One-Man Show,” New York Daily News, April 16, 1947.

- Red Smith, “VIEWS OF SPORT: All Was Quiet in Flatbush,” New York Herald Tribune, April 16, 1947.

- “How Courier Went to Press…With Jackie Robinson…On Opening Day,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 26, 1947.

- “New York Scribes’ View of Robinson’s Major Bow,” Sporting News, April 23, 1947, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Ward Morehouse, “Debut ‘Just Another Game’ to Jackie,” Sporting News, April 23, 1947, Jackie Robinson Museum.

Though Jackie Robinson traveled across the country to participate in the struggle for civil rights, one of his biggest contributions to the movement was close to home. So close, in fact, it was literally in his backyard. On the final Sunday in June 1963, Jackie, Rachel, and their children hosted their first “Afternoon of Jazz” concert on their lawn in Stamford, Connecticut, raising thousands of dollars for the cause. The concerts went on to become an annual tradition through which the Robinson family and their allies could express their love for great music and their commitment to equal opportunity.

The year 1963 was the culmination of a wave of changes that had been shaping the Civil Rights Movement since the Montgomery Bus Boycott almost a decade earlier. The battles were no longer being fought solely in courthouses and state legislatures; instead, people of all backgrounds were taking to the streets. These mass mobilizations across the South were drawing both international attention and violent repression, and leaders were growing fearful for the struggle’s continued growth. More critically, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s strategy of using mass civil disobedience to overwhelm local jails had created a new demand for bail money. The SCLC knew they needed cash, and they knew exactly who could help them get it.

Jackie, Rachel, Sharon, and David Robinson gather with musicians Herbie Mann (with flute) and Ben Tucker (with bass) at the family’s second Afternoon of Jazz in September 1963. Associated Press

Since his retirement from baseball, Jackie Robinson had emerged as one of the most effective fundraisers for civil rights organizations. He and Rachel were also great fans of jazz. With the help of longtime friend, activist, and singer Marian Logan, the Robinsons put together a star-studded lineup for a benefit concert.1 Dave Brubeck, Cannonball Adderley, Dizzy Gillespie, and others entertained a crowd of 500 assembled on the gently sloping hillside behind the Robinsons’ house. The performers contributed their time and talent for free, while the Robinson kids sold concessions and ushered guests. The $15,000 raised (about $150,000 in 2025 dollars) went directly to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

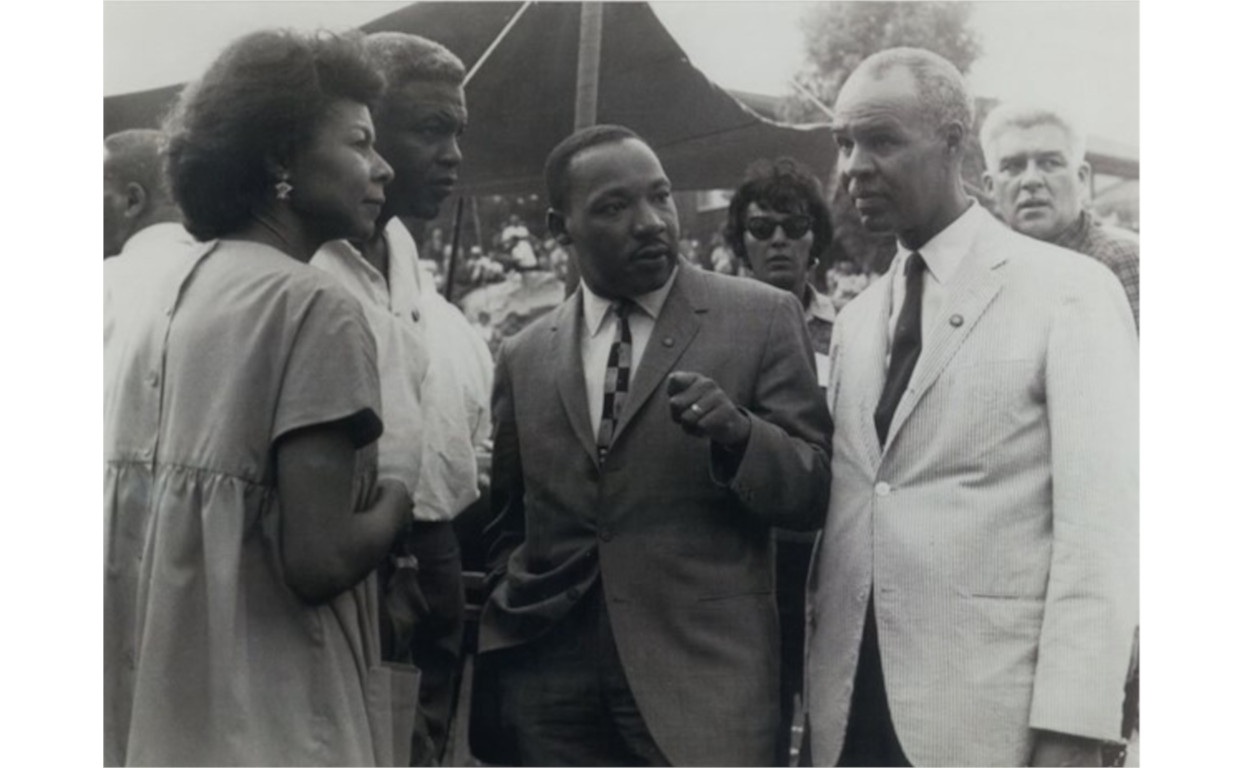

In 1963, soon after Jackie and the family returned from the March on Washington in the nation’s capital, the Robinsons held another concert on their lawn. Remarkably, the second iteration of the Afternoon of Jazz was even more successful than the first. This time, 1,300 turned out for a joint fundraiser for the SCLC and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. This time, Billy Taylor and Joe Williams headlined the show. Both Martin Luther King Jr., founder and president of the SCLC, and Roy Wilkins Jr., Executive Secretary of the NAACP, were able to attend.

Rachel and Jackie speak to Martin Luther King, Jr. (center right) and Roy Wilkins Jr. (right) at the second Afternoon of Jazz concert. Peter Simon, Jackie Robinson Museum

For Robinson, this was a unique triumph. These two civil rights organizations were vastly different in character: The NAACP, which has existed since 1909, had fought for progress in state legislatures and the courts for over five decades. The SCLC, on the other hand, dates back only to 1957. The group’s emphasis on nonviolent mass mobilizations had helped shape the popular character of the most recent phase of the movement, opening new terrains of struggle. While they shared some overlapping goals, the organizations used different tactics and often competed with each other for funds. Robinson’s concert created an opportunity for the two leaders (and their allies) to join together, allowing them to discuss strategy, rally supporters, and prepare for the battles ahead. The second concert captured the essence of the Robinson family’s emphasis on building the movement: To Jackie, it was not merely enough to be a famous voice that could write a big check. He wanted to bring people together using the tools at his disposal and encourage others, especially Black athletes and musicians, to show their support as well.

The first two Afternoons of Jazz passed with little fanfare. No live albums were recorded and no broadcasts were transmitted around the globe. No tell-all documentaries were filmed, and no jazz critics left prolix reviews of the concerts on the pages of national newspapers. The only major press that showed up was a LIFE photographer who contributed a short spread near the back of the next week’s issue.2 For Robinson and the performers, the money and the camaraderie were more than enough. Events like these helped build the movement when the demand for bail money couldn’t have been greater.

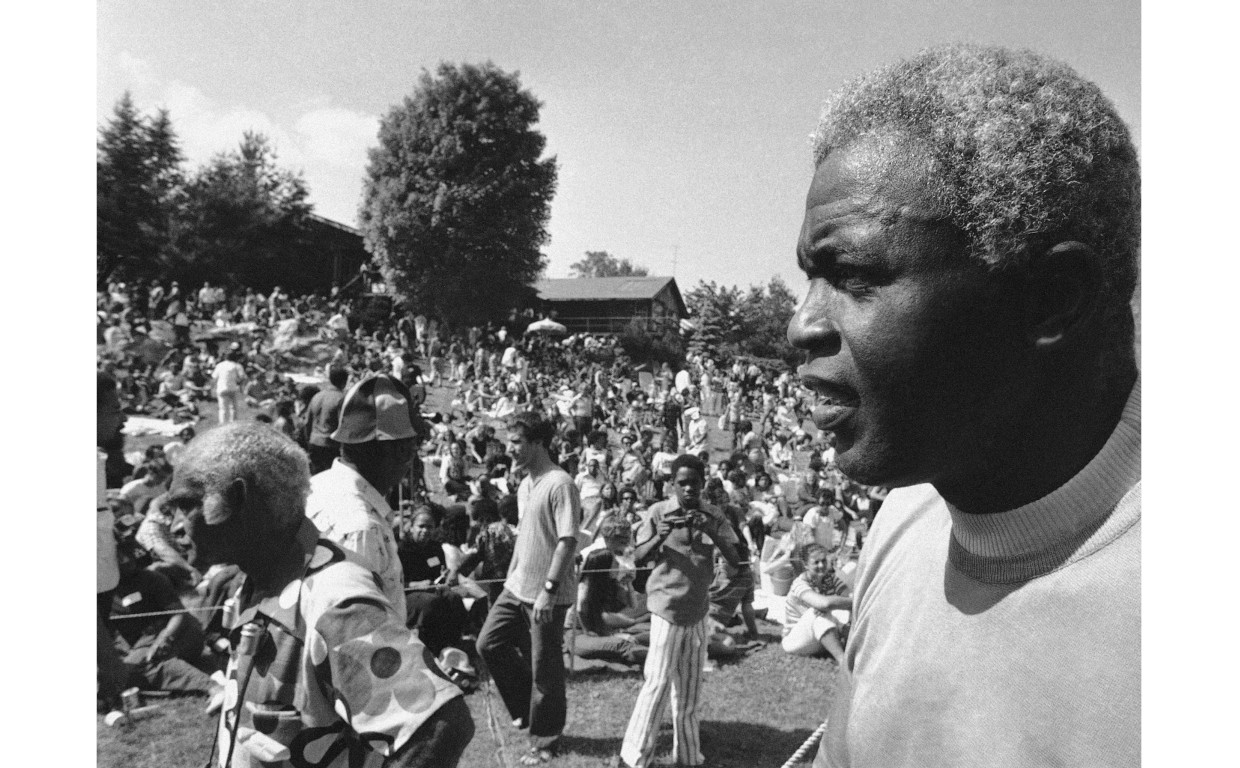

Jackie Robinson at the June 27, 1971 Afternoon of Jazz. This concert, largely organized by Jackie Jr., was a fundraiser for Daytop, a residential drug rehabilitation center where he served as a counselor. Tragically, Jackie Jr. was killed in a car accident ten days prior to the concert. The Robinson family decided that the concert would take place as planned to honor the memory of the man who worked tirelessly to put it together. Associated Press

As for the concerts themselves, they became an annual tradition for the Robinson family. The 1964 Afternoon of Jazz raised $27,000 to build a community center in Mississippi in honor of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three voting rights organizers murdered by white supremacists in June of that year.

Concertgoers gather for the 1980 edition of the Afternoon of Jazz. Jackie Robinson Foundation

For Robinson, the two 1963 concerts allowed him to continue to deepen his connections with the leaders that were building the ongoing Civil Rights Movement. They showed that his commitment to the cause went beyond public rallies and marches. Like his allies across the organizations with whom he collaborated, Robinson cared deeply about the inner workings of the movement and wanted desperately for it to succeed. Robinson’s contributions to the fight for civil rights cannot be fully measured in American dollars, nor would he wish them to be. Even so, as the jails began to fill and the future of the movement grew more dire, Jackie knew how much every cent could count.

References

- Jackie Robinson, “Two Soldiers Take A Rest,” New York Amsterdam News, September 21, 1963.

- “$15,000 for Civil Rights,” LIFE, July 5, 1963.

On January 22, 1957, copies of Look magazine flew off the shelves at newsstands around the United States. The reason for the excitement was no mystery: Look had scored a huge sports scoop. After ten years with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Jackie Robinson was announcing his retirement from baseball. The brief story—only two pages long—appeared at the end of the magazine with little fanfare beyond a small press conference. The story touched off a wave of furor, as team executives and journalists accused Robinson of disloyalty to the game and the press. However, by leaving baseball on his own terms, Robinson used his retirement to secure financial stability for his family in the years to come.

Jackie Robinson waves to photographers and journalists as he exists the Dodgers clubhouse for the final time. Getty Images

By the end of 1956, Jackie knew that his journey in baseball was coming to a close. Even so, he had performed effectively during the Dodgers’ ‘56 campaign and suggested that he was ready to return the next year. His .275 batting average was 21 points better than the year before, and his clutch hitting in the World Series that year kept the Dodgers in contention until their Game 7 blowout loss. Though his competitive spirit still burned, Robinson, now 38 years old, knew it would soon be time to hang up his spikes. His financial advisor, Martin Stone, had been searching for career opportunities for Robinson for a few years. By the beginning of December 1956, Robinson was in talks with Chock full o’ Nuts, a New York coffeeshop chain, to serve as vice president of personnel. Having secured a contract with William Black, the owner of Chock, Robinson’s exit from baseball was all but assured.

Jackie greets workers at a Chock full o’Nuts restaurant in March 1957. Getty Images

Robinson’s retirement, however, needed to be kept a secret. Years earlier, he had signed a contract with Look magazine for $50,000 over two years, offering the Iowa-based publication the exclusive rights to the story. The job at Chock (an executive position placing him in charge of the chain’s foodservice personnel) would pay $30,000 a year—a number comparable to the salary he expected to make with the Dodgers in 1957. Though the contract was inked, the plan was to not announce the position until Look went to print.

While Robinson was getting his affairs in order, the Dodgers threw him a curveball in the middle of December: Robinson was traded to the New York Giants. Robinson was dealt to the Dodgers’ crosstown rival for $35,000 and Dick Littlefield, a journeyman pitcher of middling talent. The blockbuster deal (and the suggestion that Robinson stood to make over $50,000 from the Giants in 1957)1 indicated that even at 38, Jackie still had big league talent. As Robinson finalized his plans, he begged the two baseball organizations to keep the deal a secret.2 They refused.

Rachel, David, and Jackie hold Giants ephemera at their Stamford, Connecticut home, December 1956. Associated Press

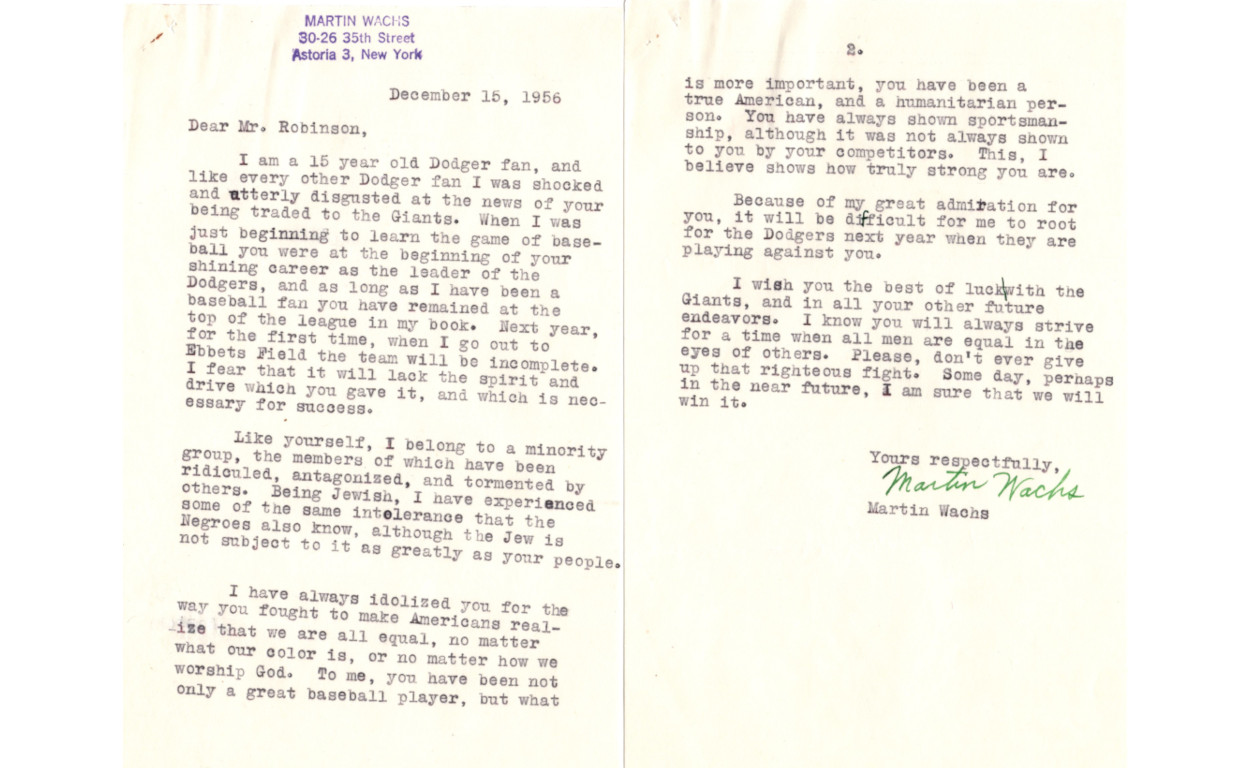

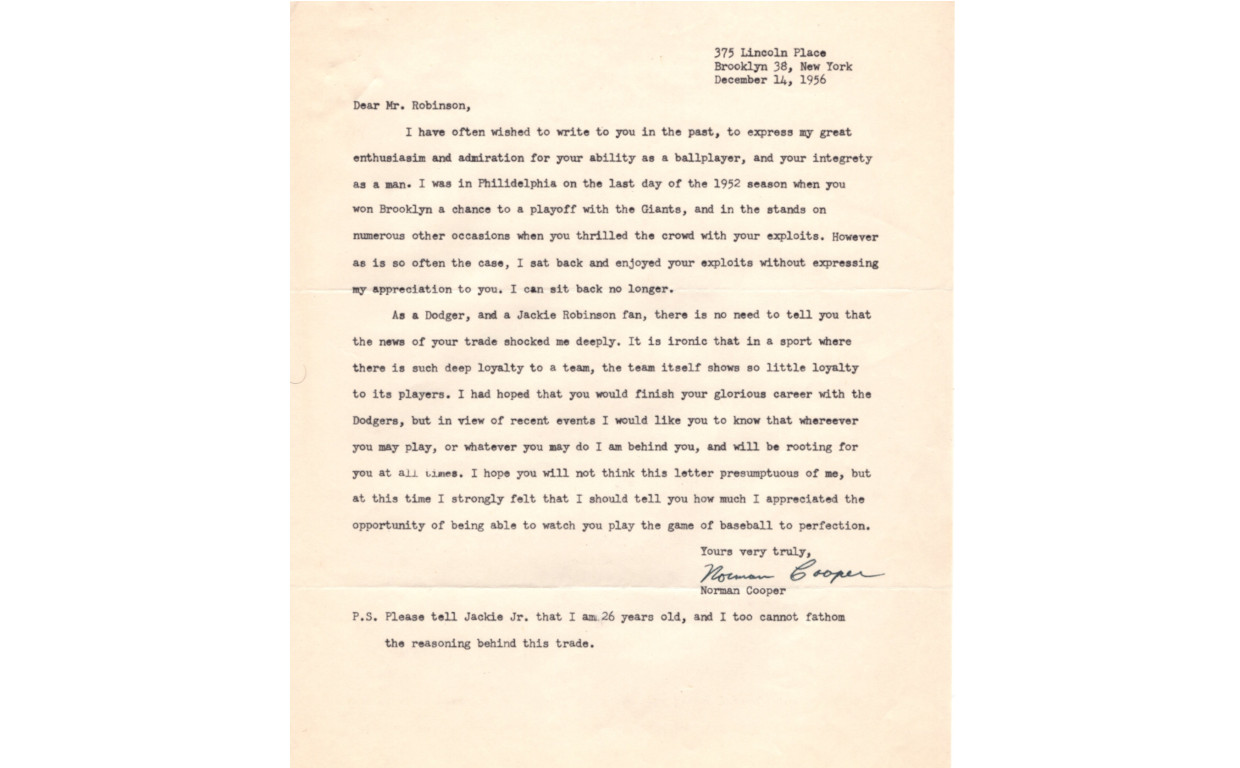

Immediately, the Dodger office on Montague Street was deluged with hate mail. For ten years, Robinson had been the face of the Dodgers. A trade (to a hated rival no less!) was unimaginable. “Sometimes I suspect that all of you in the organization” an anonymous letter-writer offered, “would sell your grandmothers to the Green Bay Packers if you could turn an honest dollar doing so…I suggest that you also trade all your other standbys…[T]hink of all the money you could make.”3 Robinson got letters of support from Brooklynites as well: “It is ironic,” said a local Brooklyn fan, “that in a sport where there is such deep loyalty to a team, the team itself shows so little loyalty to its players.”4 Other letter writers expressed hope that Robinson would simply retire rather than play for the Giants.5 Those fans would get their wish.

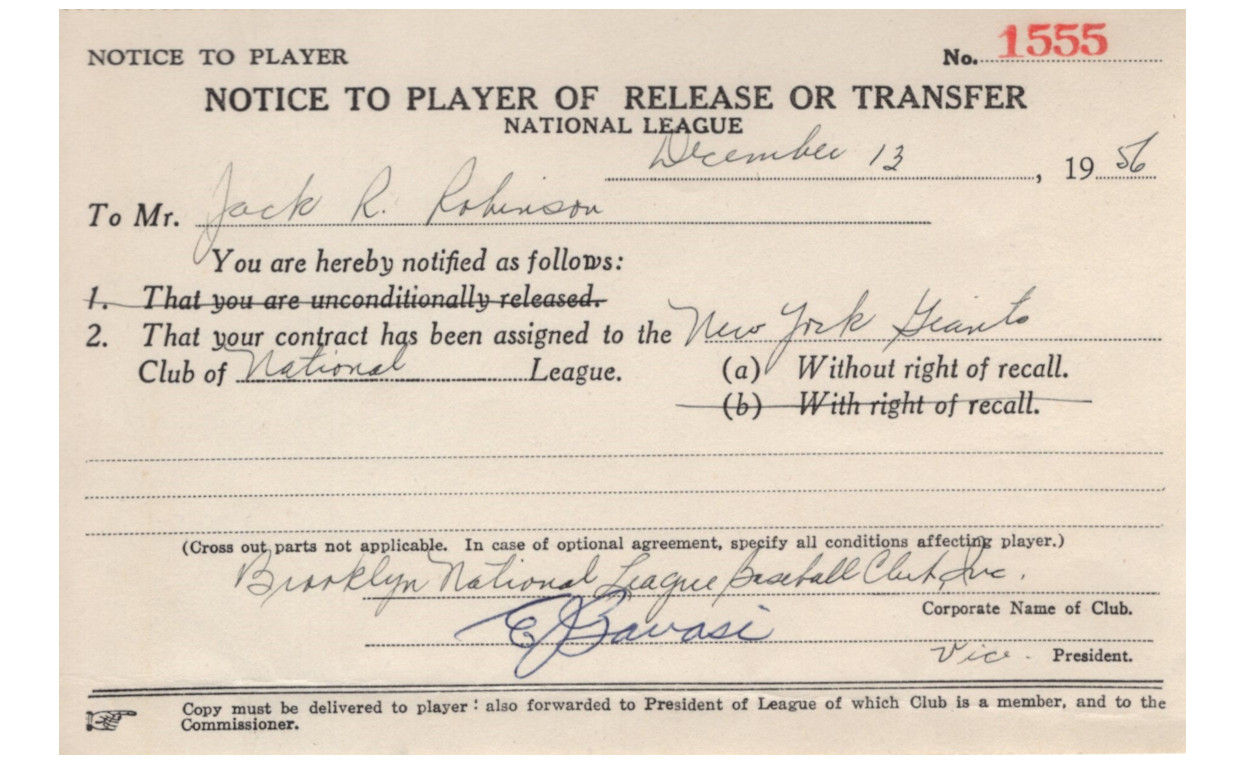

Notice of Transfer given to Jackie Robinson informing him of his trade to the New York Giants. Buzzie Bavasi’s signature appears at the bottom. Jackie Robinson Museum

By the first week of January, Robinson’s secret was out. Even before Lookwent to print, the story leaked, setting off a new wave of vitriol. This time, however, much of it was directed at Jackie, and it came from an expected source: Dodgers management itself. Soon after it became apparent that Robinson had sold the story to a newsmagazine, Buzzie Bavasi, the team’s general manager, took a swipe at Robinson in the press. “That’s typical of Jackie,” he scoffed. “Now he’ll write a letter of apology. He’s been writing letters of apology all his life.”6 Bavasi went on to accuse Jackie of betraying the New York sportswriters who had been covering him for the previous ten years.

A letter from Martin Wachs, a young Dodger fan bemoaning the trade to the Giants. Jackie Robinson Foundation

Letter from Norman Cooper decrying the Dodgers’ disloyalty to Robinson. Jackie Robinson Museum

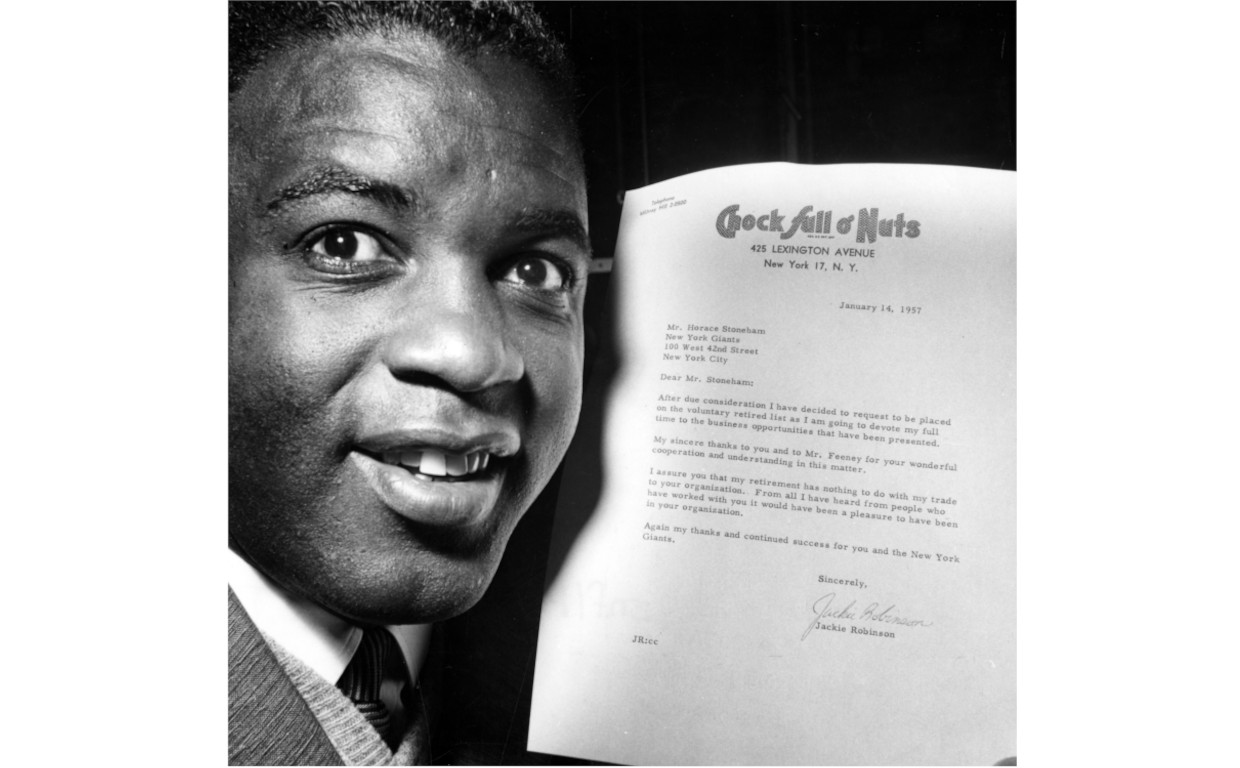

Robinson was taken aback. While his relationship with Bavasi had been at times stormy over the previous half-decade, Robinson was particularly incensed by Bavasi’s comments. “After I read what Buzzie Bavasi said, I wouldn’t ever play again,” he declared.7 The trade was null and void. Littlefield and the $35,000 returned to the Giants and Robinson began to settle into his life as a business executive.

Jackie Robinson holds up a letter informing Giants owner Horace Stoneham of his retirement. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

His retirement was hotly debated in the press: Though many New York writers assailed Robinson’s decision to sell his retirement story, it earned him plenty of defenders across the country as well. “Perhaps it is small townish of this writer to take such a stand,” wrote Marvin E. Miller of the Lancaster, Pennsylvania Daily Journal-Intelligencer.8 “But we cannot…understand how any sportswriter can figure an athlete owes him anything.” John Hanlon, writing in a Providence, Rhode Island newspaper, went so far as to say that the sportswriters owed him: “His story always sold,” Hanlon said, referencing Robinson’s willingness to opine to the press over ten years with the Dodgers.9 “He was not only bread and butter to the reporters’ daily menu, but frequently their steak and wine, too.” Across the country, weekly columns and letters to the editor praised Robinson for leaving the game. Rachel Robinson saved many of these positive responses in the family scrapbooks.

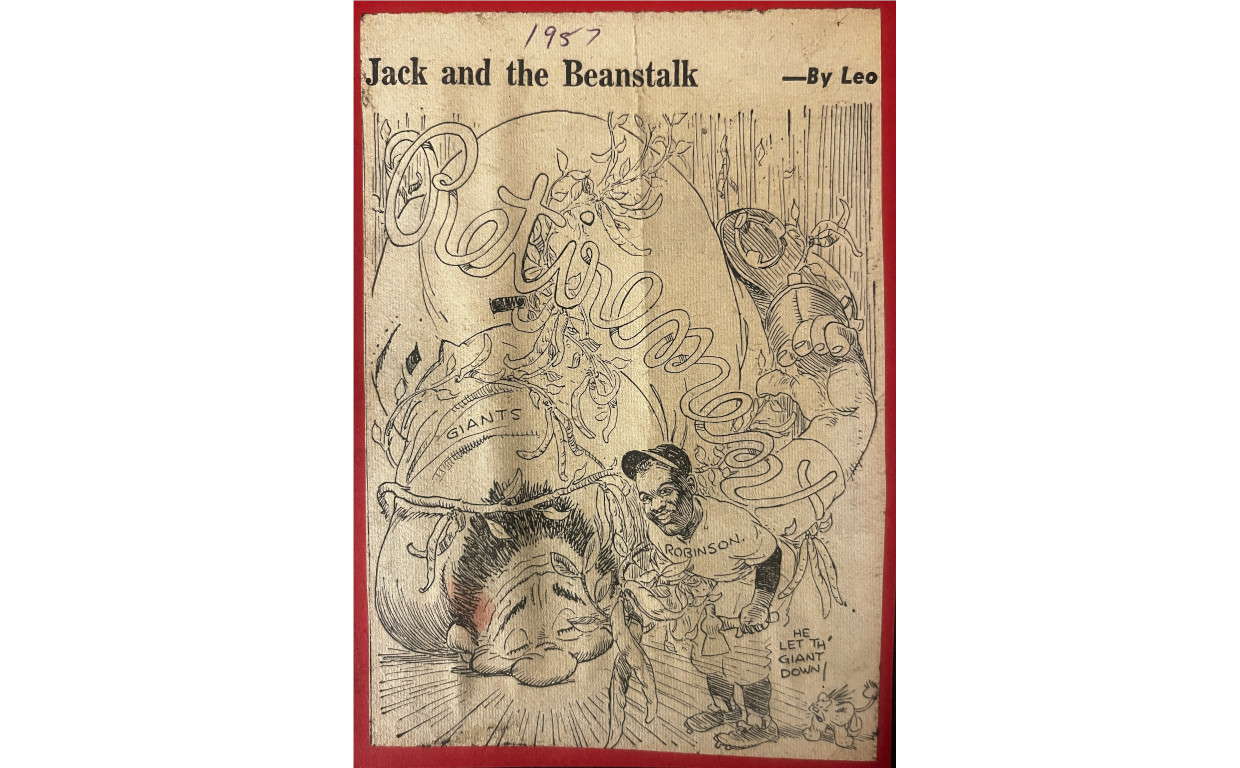

A cartoon by Leo O’Mealia in an early 1957 edition of the New York Daily News. A smiling Jack(ie) Robinson, holding a hatchet, has cut down the beanstalk, causing the New York Giant to crash to the earth. Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum

Jackie, for his part, was pleased with his decision. “Personally,” Robinson later wrote in his autobiography in 1972, “I felt that Bavasi and some of the writers resented the fact that I outsmarted baseball before it outsmarted me.”10 Robinson was able to leave baseball by his own choice and start a lucrative career outside of it. In his era, few players were able to say the same.

Building a career outside of baseball was always important to Robinson. When he was promoted to the Dodgers at age 28, he knew that his career in baseball might not be long. As early as his rookie season, he would often say that he only expected to be in baseball for three years.11 Keen to realize financial security outside of the game, Robinson sought out a diverse range of business opportunities during his post-baseball career. The business knowledge he was able to gain during the winter months between seasons allowed him to transition smoothly into his job at Chock, which he held until 1964.

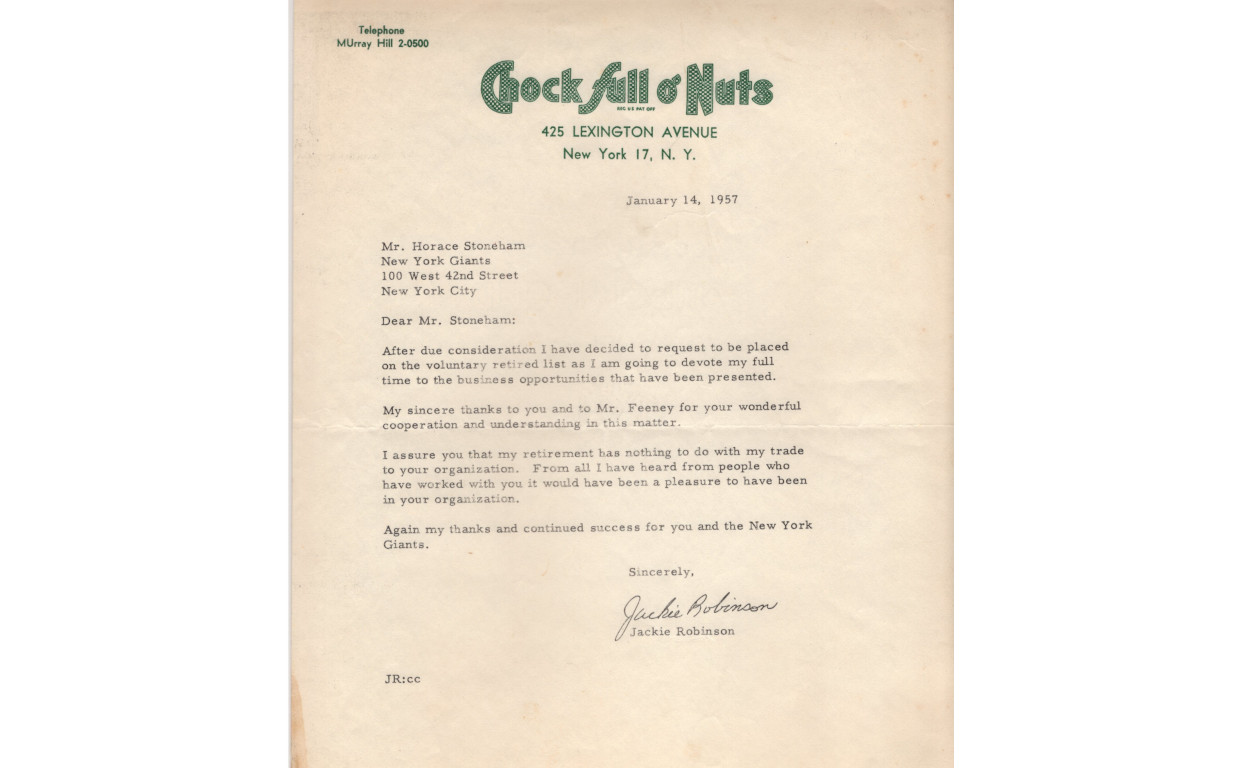

Letter from Jackie Robinson to Giants owner Horace Stoneham. Robinson, writing on Chock stationery, requested to be placed on the voluntary retired list, confirming his exit from baseball. Jackie Robinson Museum

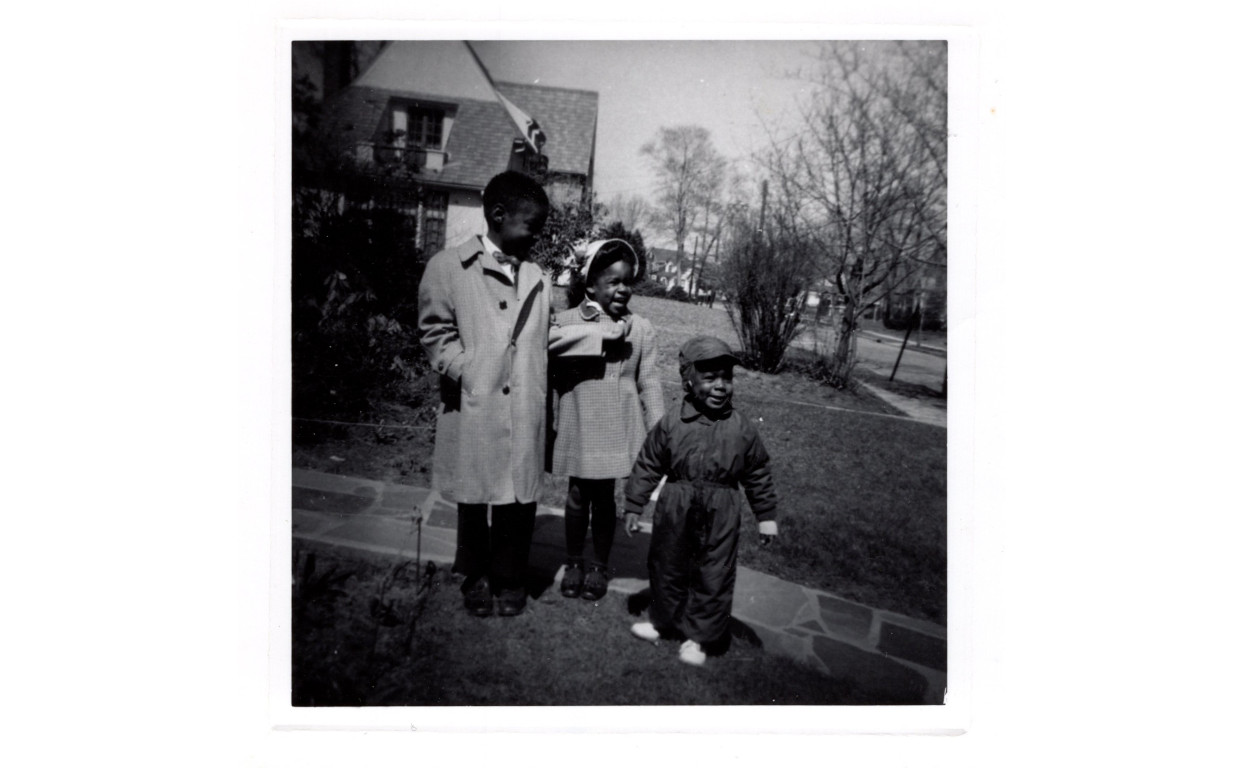

As for the Look story itself, it was brief and to the point. Robinson confirmed to his readers that his trade to the Giants did not influence his decision to retire.12 He continued by recounting the things he would miss about baseball: his teammates, the fans, and even the umpires with whom he often feuded. He apologized to the reporters who had hounded him over his decision to honor his contract with Look. Finally, he ended on a personal note, describing how his sons Jackie Jr. and David burst into tears over his retirement from baseball; his daughter Sharon, for her part, was excited that her father would be home more often. “It’s tough for a 10-year-old to have his dad suddenly turn from a ballplayer into a commuter,” Robinson concluded. “But someday Jackie [Jr.] will realize that the old man quit baseball just in time.” Indeed, Robinson left baseball on his own terms. His exit from the game opened doors for him both in business and the growing struggle for civil rights. As he moved through life beyond the confines of Ebbets Field, he was finally able to do so as his own man.

References

- New York World Telegram. “Jackie Adamant, Rejects 50G Plus.” Early 1957. Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Jimmy Cannon, “We Came out of the Theater…,” January 1957, Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- “1957 Unsigned Camden Drive Letter to E.J. Bavasi on Robinson Trade,” December 20, 1956, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Norman Cooper, “1965 Norman Cooper Letter to Jackie Robinson,” December 14, 1956, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Ethel Stiles, “1956 Ethel Stiles Letter to Jackie Robinson,” December 13, 1956, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Gordon S. White, “Wavering Ended, Player Contends,” New York Times, Early 1957, Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum

- White, “Wavering Ended, Player Contends.”

- Miller, Marvin E. “Robinson Beats Baseball Brass At Own Game.” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer Journal, January 10, 1957. Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- John Hanlon, “One Man’s Opinion On Robinson Case,” Providence Evening Bulletin, January 8, 1957, Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 134

- Morehouse, Ward. “Debut ‘Just Another Game’ to Jackie.” Sporting News, April 23, 1947.

- Robinson, Jackie. “Why I’m Quitting Baseball.” Look, January 22, 1957. Jackie Robinson Museum.

At the beginning of the 1949 season, the Robinson family left their Flatbush apartment for a new home in the St. Albans neighborhood of Queens. In doing so, they joined a vibrant Black community in the Addisleigh Park section of the neighborhood. Throughout the forties and fifties, St. Albans was home to a wide range of Black musicians, actors, and athletes. Despite opposition from their white neighbors, and the neighborhood’s past as a segregated community, these entertainers and their families helped build a local legacy that still resonates today.

(l to r) Jackie Jr., Sharon, and David Robinson stand in front of the family home in St. Albans. Jackie Robinson Museum

By 1949, the Robinsons were realizing that their home, the second floor of a two-story house on Tilden Avenue in Flatbush, would soon be too small. Jackie Jr. was approaching his third birthday, and a second child, Sharon, was on the way. The family was looking for more space, which meant a move further from Ebbets Field than Jackie Robinson had lived since joining the Dodgers. In the middle of Jackie’s career-high 1949 season, Rachel found the family a new home, located at 112-40 177th street in the St. Albans neighborhood of eastern Queens.

112-40 117th Street, where the Robinsons lived from 1949 to 1954. Jackie Robinson Museum

Like many suburbs and neighborhoods in the Northeast, St. Albans carried a racist history. Planned as a railroad suburb in the early 1900s, the area quickly became home to hundreds of moderately well-off white families seeking to move outside of the city.1 While the area was not formally segregated when it was first developed, restrictive housing covenants were put in place in the 1930s and 40s, barring property owners from selling their home to anyone who wasn’t white.

A row of houses in Addisleigh Park in 2015. Wikimedia Commons

Covenants like these governed thousands of suburbs and neighborhoods throughout the early twentieth century. Crucially, these covenants were not formally laws: in 1917, the Supreme Court ruled in Buchanan v. Warley that zoning codes enforcing segregation were unconstitutional. Instead, these restrictions were written into the deeds of the properties themselves, declaring that they could not be sold or rented to Black people (or, in many cases, other racial and ethnic minorities). Generally, every property in a neighborhood or town would have such a clause written into the deed. In the 1930s, having such a covenant was often a requirement for receiving a mortgage backed by the Federal Housing Administration.

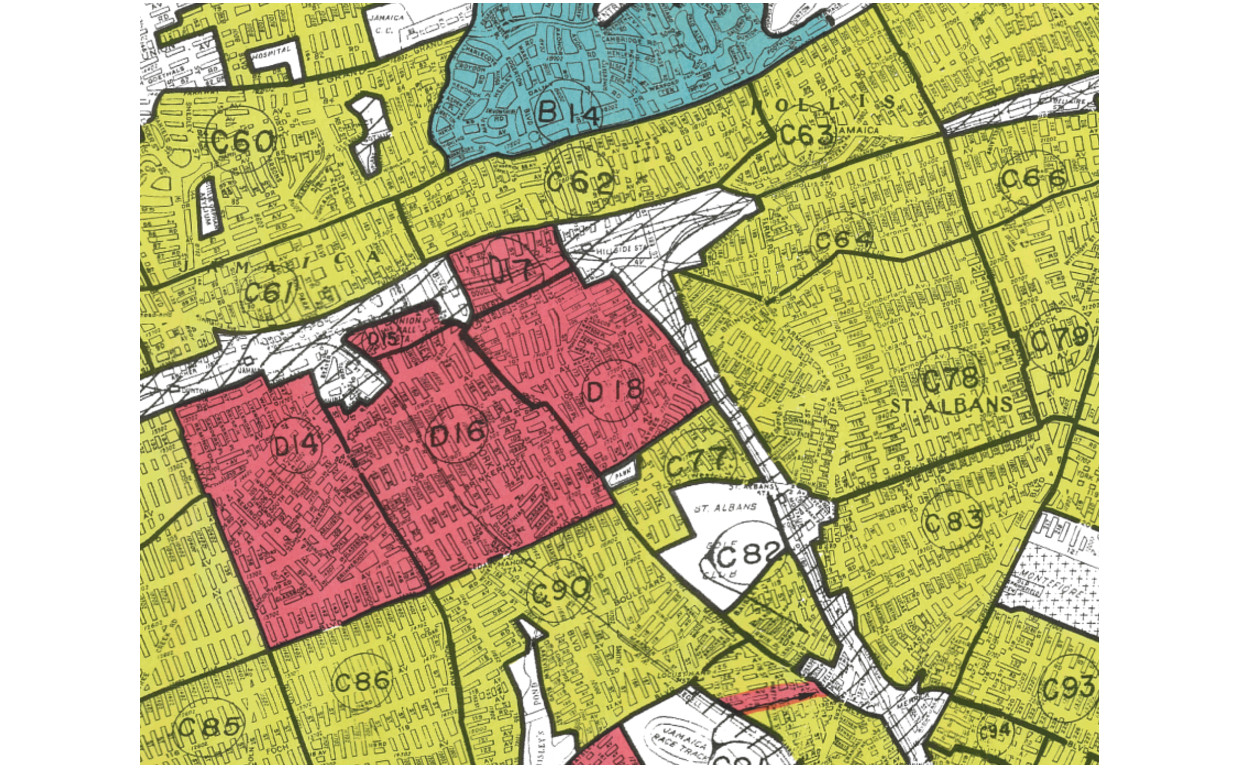

A redlining map of the St. Albans Area. Public Domain, courtesy of Mapping Inequality

Between 1935 and 1940, the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) produced a series of maps of every major American city, assigning labels to different neighborhoods based on how desirable they were to mortgage lenders. Areas with a sizeable Black population were given red labels, indicating that they were the least desirable for banks. This process came to be known as redlining. While these maps themselves were not necessarily used to determine whether an individual borrower would receive a loan, they reflect and codify racist practices that were already widely in use. Residents of red areas typically paid higher interest rates on mortgages—if banks were willing to lend to them at all.

The Robinsons moved into their home (located in the section labeled C77) in 1949, about a decade after HOLC produced these maps. According to the accompanying report, section C77 had a “gradual encroachment of Negroes from the north” (section D18), terminology suggesting that the creators of these maps regarded Black families both as economically undesirable and potentially dangerous to white homeowners. Further, the report noted that many other sections would have a downward “trend of desirability over the next 10-15 years,” reflecting the racial beliefs of both HOLC and other institutions who had designed similar maps in the twentieth century.2

In 1948, the Shelly v. Kraemer Supreme Court decision rendered racial covenants unenforceable, though redlining and other related practices continued. Even before then, a trickle of Black families had been moving to St. Albans as homeowners deliberately broke the covenants in their deeds. Other white residents fought back with lawsuits and racist leaflets.3 Refusing to welcome their new neighbors (and attempting to preserve their property values), many of them left. In their place, a larger wave of middle-class Black families began to arrive. Alongside them came a number of prominent entertainers. Beginning with jazz greats Count Basie and Fats Waller years earlier in 1940, musicians began to turn the area into a vibrant community. Other artists, athletes, and intellectuals followed soon after. Eventually, Ebony published an article (complete with the names and addresses of many famous residents!) boasting that St. Albans was “home for more celebrities than any other U.S. residential area.”4

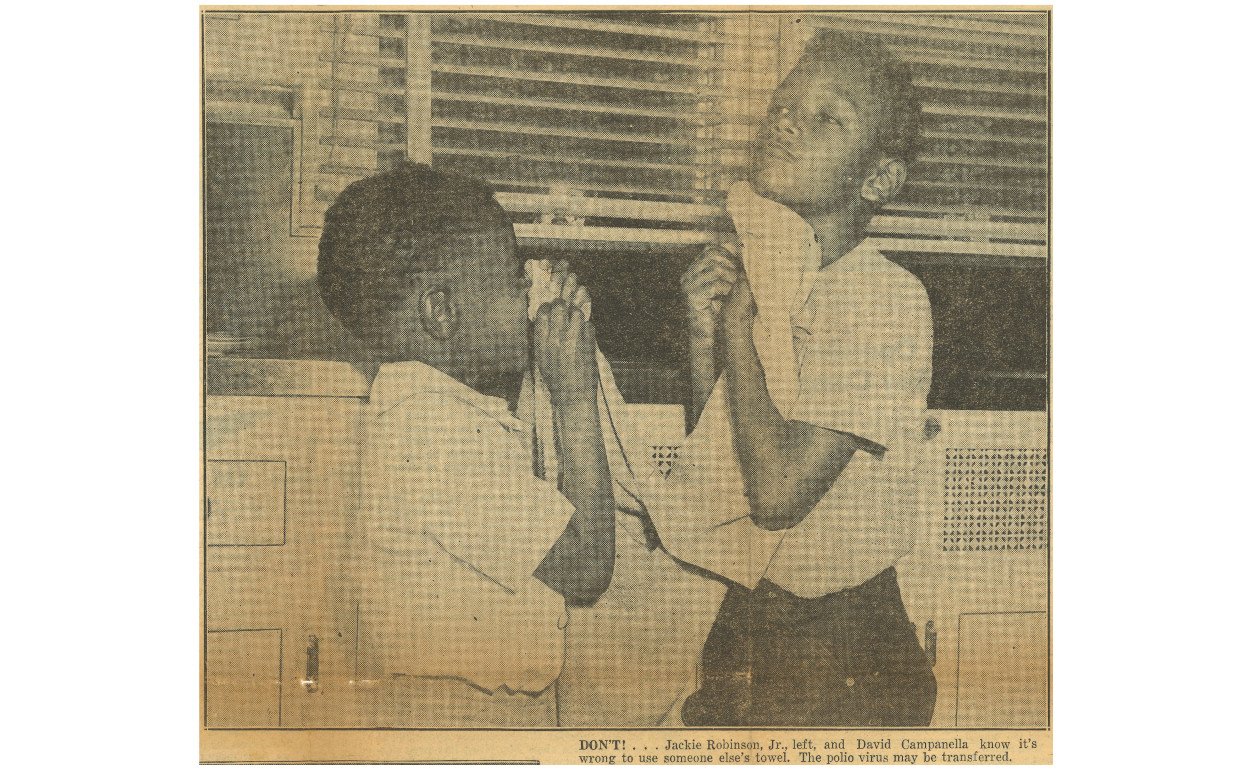

Friends Jackie Robinson Jr. and David Campanella demonstrate less-than-ideal towel use in a 1951 polio prevention public service announcement. New York Amsterdam News, Jackie Robinson Museum

Roy Campanella, Robinson’s Dodgers teammate, moved to St. Albans in 1948. After Jackie and the family arrived the next year, Jackie Jr. and David Campanella, Roy’s eldest son, became close friends, enjoying the community they shared in their new neighborhood. Though the family now lived miles away from Ebbets Field, privacy was still impossible. Jackie recounted how baseball fans would constantly swarm the house, taking pictures and demanding to see the children. “Usually, Rachel was diplomatic with the intruders,” Jackie later recounted. “But some of the liberties people took got on her nerves.”5

Between 1946 and 1955, the list of famous names grew. Actress Lena Horne was the next to arrive, and other jazz musicians such as Ella Fitzgerald and Illinois Jacquet followed shortly afterward. Later, saxophonist John Coltrane and funk rocker James Brown moved in the 1960s. Political theorist and activist W.E.B. DuBois also called St. Albans home, as did his wife, Shirley Graham DuBois, whose novels and musical works continue to shape our understanding of race in America today.

Rachel and Sharon Robinson pose for the camera on the sidewalk in front of their St. Albans home. Jackie Robinson Museum

Robinson and Campanella weren’t the only athletes in town, either. Heavyweight champ Joe Louis (who had collaborated with Robinson to desegregate the Army’s Officer Candidate School during World War II) moved in 1955. Floyd Patterson, also a heavyweight title holder, lived in St. Albans as well. Patterson and Robinson would work closely together in the 1960s, traveling together to speak at civil rights rallies and even attempting to start an ill-fated housing development.

The Robinsons left St. Albans in 1954. Searching for a retreat from their busy city life (and the too-friendly-by-half baseball fans that came along with it), the family moved again, this time to a new home in Stamford, Connecticut. The Robinsons’ St. Albans house still stands today, as do many of the original homes in Addisleigh Park. For Jackie Robinson and the family, the neighborhood was not just a symbol of a changing America, but a home in which they could share in the growing racial diversity that defines New York City. Though Jackie Robinson’s stay in the neighborhood was brief, he helped build its culture into a vibrant Black enclave at the edge of Queens.

References

[1] Theresa C. Noonan, “Addisleigh Park Historic District Designation Report” (New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, February 1, 2011). https://smedia.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/2405.pdf

[2] Nelson, Robert K., LaDale Winling, et al. “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.” Edited by Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers. American Panorama: An Atlas of United States History, 2023. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining.

[3] https://www.untappedcities.com/explore-queens-addisleigh-park-the-african-american-gold-coast-of-ny/

[4] “St. Alban’s,” Ebony, September 1951.

[5] Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 116

Last week, we explored Jackie’s performance in the 1947, 1949, and 1952 World Series, as well as a “phantom” program from the never-played 1951 Dodgers-Yankees matchup. As the series returns to New York, we will look at Robinson’s four other World Series against the Yankees between 1953 and 1956. In celebration of the historic Dodgers-Yankees rivalry, the Jackie Robinson Museum will be open for special hours on Tuesday, October 29 and Wednesday, October 30 from 11AM to 6PM!

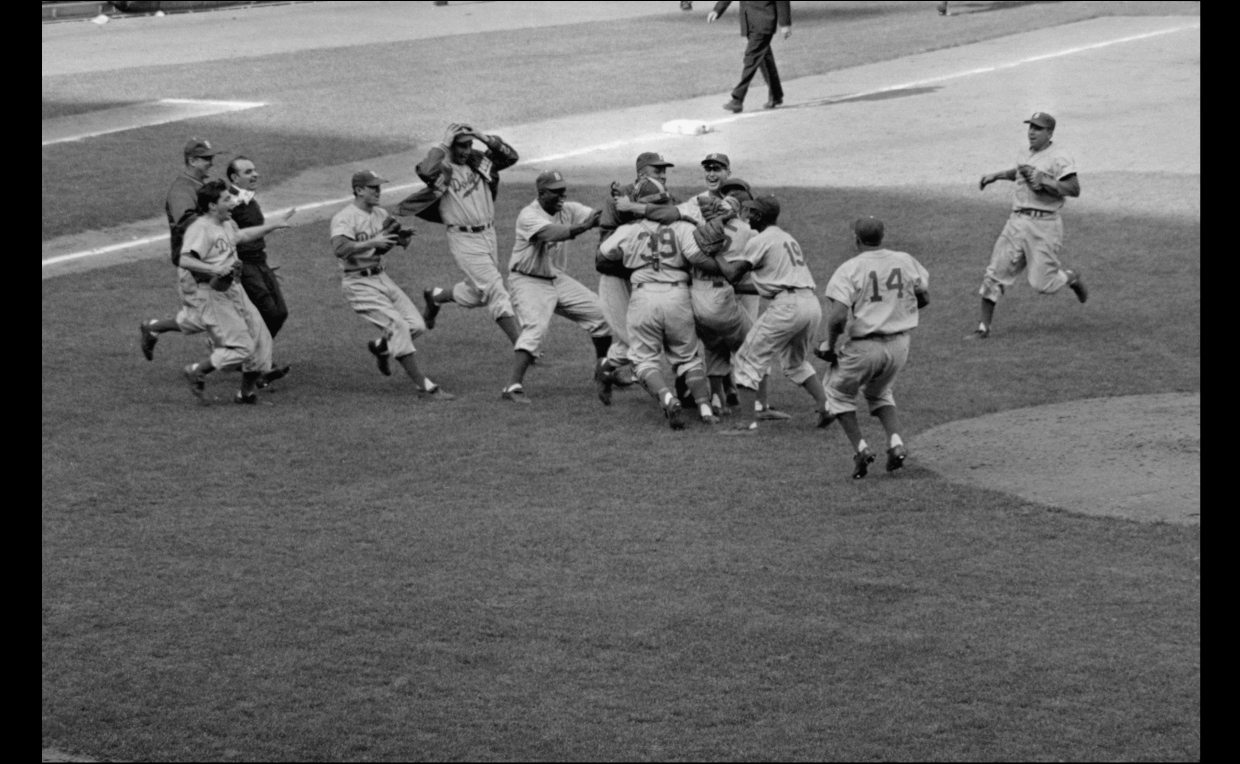

Dodgers players mob pitcher Johnny Podres after he pitches a complete game shutout in the 1955 World Series. Getty Images

1953

After their crushing defeat in 1952, the Dodgers returned to the World Series the next year. Winning an impressive 105 games, the Dodgers cruised to the National League pennant, coming in thirteen games ahead of Milwaukee. Again, they were pitted against the New York Yankees, who were looking to add to their streak of World Series victories. The 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers are considered one of the best teams of all time. Expectations were high, even though the Yankees were considered 6-to-5 favorites. Even Jackie didn’t want to seem overconfident: “I don’t want to bat 1.000,” he said before the series started. “I just want to get a hit at the right time.”

Robinson, of course, did not bat 1.000, but he had his most successful World Series to date. After getting only a single hit across the Dodgers’ losses in Games 1 and 2, Robinson’s bat jumped to life as he went 4-for-8 in Brooklyn’s victories at home in Games 3 and 4. In Game 5, the Yankees won an 11-7 slugfest backed by a grand slam from Mickey Mantle, sending the series back to the Bronx.

In Game 6, the Yankees jumped to an early 3-0 lead against the Dodgers Carl Erskine. In the bottom of the sixth, however, Robinson doubled with one out. Realizing that his team needed a spark, Jackie provided it the way he knew best: by taking the next base. With MVP catcher Roy Campanella at the plate, he broke for third base and made it easily. Campanella then scored him on a groundout, making it 3 to 1. The Dodgers would rally again in the top of the ninth, tying the game on a Carl Furillo home run. In the bottom of the frame, however, Billy Martin poked a single up the middle to score the Yankees’ winning run, giving them their fifth World Series victory in a row.

1955

Robinson lashes a triple in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series.

The 1955 Dodgers entered the World Series as 98-game winners as they headed to Yankee Stadium once more. Across the first five innings of Game 1, the two teams traded blows as starting pitchers Don Newcombe and Whitey Ford struggled to retire the side. Robinson was an important factor in the early phases of the game, hitting a triple to center in the top of the second and scoring on Don Zimmer’s single. By the top of the eighth, however, the Yankees had pulled ahead, 6 to 3. Carl Furillo singled and Robinson had dashed to second on an error. After a sacrifice fly scored Furillo, Robinson waited at third with his team down by two.

After timing the tiring Ford’s delivery, Robinson dashed for home and barely slid beneath the tag of Yogi Berra, completing the steal of home. Berra was furious, immediately leaping to his feet to argue Larry Summers’s safe call. Even though the Dodgers were down two runs (and indeed, would go on to lose 6 to 5), Robinson was proud of his choice. “When they give me a run, I’m going to take it,” he later quipped, as the Dodgers prepared for Game 2. To Robinson, this steal was the jolt that the Dodgers needed. 36 years old and nearing the end of his career, Jackie was still terrifying opposing pitchers with his speed and daring.

Jackie Robinson steals home in the eighth inning of Game 1.

The Dodgers dropped the next game as well. The next day, they returned to the friendly confines of Ebbets Field for Game 3. With the home crowd at their backs, the Bums’ fortunes began to change. Roy Campanella went 3-for-5 with a double and a home run. Robinson continued his reign of terror as well: When he doubled in the bottom of the seventh, he goaded Yankees’ left fielder Elston Howard into throwing to the base behind him, allowing Jackie to run to third as well. All in all, the Dodgers combined for eight runs, securing victory in the third game.

Robinson reaches third after Elston Howard throws behind the runner.

Victories in Games 4 and 5 brought the Dodgers within one game of victory as the series returned to the Bronx. Again, it was Snider and Campanella who anchored the lineup as they prepared for the showdown in the Bronx. A 5-1 defeat in Game 6 set up the decisive final game.

The next day, over 62,000 fans filled Yankee Stadium to see the matchup between the Yankees’ Tommy Byrne and the Dodgers’ Johnny Podres, a 22-year-old lefthander who had earned the win in Game 3. After three scoreless innings, Gil Hodges knocked in Dodger runs in the fourth and sixth, giving the Brooks a 2-0 lead. It would be defense and pitching that ruled the day, however. In the bottom half of the sixth inning, the Dodgers’ Sandy Amorós tracked down Yogi Berra’s well-struck fly to left field and then doubled off Gil McDougald at first base, ending the Yankees’ threat. Podres would go on to complete the shutout, giving Brooklyn its first ever World Series victory and netting the young pitcher World Series MVP honors.

The Brooklyn Dodgers run to embrace Johnny Podres after recording the final out.

The victory sent Brooklyn into delirious joy. Parades were held, confetti was thrown, and a local pizza parlor even held a mock funeral for the defeated Yankee dynasty. The Dodgers had never won a World Series before 1955, and celebrations lasted for days. Jackie, for his part, didn’t even play in the final game. Even so, his steal of home in Game 1 and his leadership throughout the series cemented his legacy as a dauntless competitor on baseball’s biggest stage.

This 1955 World Series ring, belonging to Commissioner Ford C. Frick, can be found in the lobby of the Jackie Robinson Museum.

1956

The Dodgers and Yankees would meet once more during Jackie Robinson’s career, in 1956. By the end of the season, Jackie was preparing to leave baseball. No longer the everyday second baseman, Robinson played most of the 1956 campaign at third, with some games at second and in the outfield as well. Still, he was an effective hitter, rebounding from a somewhat lackluster 1955.

In the second inning of Game 1, Robinson homered off of Whitey Ford. With none on and the Dodgers down 2-0 after yet another Mickey Mantle blast in the first, Robinson laced a line drive just inside of the left field foul pole, cutting the Yankee lead in half. Hodges and Furillo followed with a single and a double, tying the game at 2 apiece. The Dodgers would go on to win, 6 to 3, and would go on to win the next day in a 13-8 romp as well.

Robinson’s home run in Game 1 would be his last as a Brooklyn Dodger.

The Dodgers’ fortunes turned for the worse when the Series traveled north to the Bronx. Whitey Ford and Tom Sturdivant held the Dodger bats in check over the first two games at Yankee Stadium, surrendering only five runs between them. In the third game, the Dodgers fell victim to a perfect game thrown by Don Larsen, the only one in the history of the playoffs. Twenty-seven Dodgers came to the plate, none of whom ever reached first base.

Don Larsen’s perfect game was recorded by a fan in the official program from the 1956 World Series; 1956 World Series Ticket; and Stadium Club pass for Game 5. Jackie Robinson Museum

Humiliated in Game 5, the Dodgers returned to Brooklyn determined to fight back. For the first nine innings, Yankee hurler Bob Turley was almost as effective as Larsen the day before, giving up only three hits and no runs. Luckily for the Dodgers, Clem Labine was equally brilliant, scattering seven hits across ten innings of shutout ball. In the bottom of the tenth inning, with the series on the line, Robinson came to the plate with Jim Gilliam on second. On a 1-1 count, Robinson lined a base hit off the left field wall, just out of reach of a leaping Enos Slaughter. As Gilliam raced around to score the winning run, Robinson’s danced around the bases celebrating his walk off knock.

Robinson’s base hit (scored as a single) barely cleared the glove of Enos Slaughter. Slaughter had generated headlines nine years earlier when he deliberately spiked Robinson on a close play at first base in St. Louis.

In many ways, it was a fitting end to a brilliant career. Though he didn’t know it at the time Robinson’s walk off was his final hit in the majors. The Dodgers lost the next day, 9-0, with Robinson going without a hit. Yogi Berra hit two home runs as Don Newcombe was shelled over the first three innings of a blowout loss. Jackie was disappointed by the margin of defeat. “I didn’t mind so much that they beat us,” he said to New York Times reporter Roscoe McGowan after the drubbing. “But I hated to be beaten that way.” For Robinson, whose indefatigable competitive spirit had burned brightly for a decade, this World Series was the end of a storied career. At the beginning of 1957, he took a job as vice president of personnel at Chock full o’ Nuts, a local coffee chain, and began devoting himself to the growing civil rights struggle.

Over his career, Jackie Robinson played in over half of the World Series matchups between the Dodgers and the Yankees. His blazing speed and surehandedness in the field left an indelible mark on this historic rivalry, the legacy of which continues today. Now, a new chapter is unfolding in New York and Los Angeles. As the series returns to the Bronx, we hope you will join us at the Jackie Robinson Museum during the historic World Series this October and beyond to learn more about the triumphs and struggles of baseball’s first Black player in the modern era.

On Friday, October 25, 2024 the New York Yankees will head to Los Angeles for their twelfth World Series matchup against the Dodgers. It’s a historic rivalry—one that stretches back to the Dodgers rollicking days as “Dem Bums” in Brooklyn. No two teams have met in the World Series more often. From 1947 to 1956, Jackie Robinson played a key part in six of the eleven contests so far, terrifying Yankees pitching with his speed on the basepaths and dazzling fans with his superb fielding. This week, the Jackie Robinson Museum is celebrating the 2024 world series as these two franchises add a new chapter to their rivalry. Our galleries will be open on Tuesday, October 29 and Wednesday, October 30 as the Dodgers come to New York for Games 3, 4, and 5. Join us in person or online as we explore some video highlights and artifacts from the Dodgers-Yankees World Series in which Jackie played.

1947

Jackie Robinson steals second base in Game 1 of the 1947 World Series.

Jackie’s first World Series against the Yankees was in 1947, in his rookie year. Across the regular season, Jackie had shown he was a top-notch player. He hit .297 and led the league in stolen bases, earning first-ever the Rookie of the Year award. As a result, National League opponents were already quite familiar with Jackie Robinson’s daring on the basepaths and his superb contact hitting. The Yankees, however, still needed an introduction. In the first inning of Game 1, Jackie Robinson drew a walk against Spec Shea. On the second pitch of the next at-bat, he broke for second, sliding into the bag just ahead of catcher Yogi Berra’s throw. Two innings later, Robinson drew another base on balls and unnerved Shea into balking him to second base.

Robinson advances on a balk in Game 1 of the 1947 World Series.

Despite Robinson’s adventures on the basepaths, the Dodgers lost the first game, 5 to 3. The series was best remembered for the heroics of Dodger pinch-hitter Cookie Lavagetto in Game 4. For eight and two-thirds innings, Yankee starter Bill Levens had no-hit the Dodgers, surrendering only a single run in the bottom of the fifth. With two out and two runners on, Lavagetto lashed a double to right that scored both runners for a walk off win, evening the series at two games apiece. They would go on to lose the series in seven games. Robinson could not replicate his excellent hitting from the season, hitting only .259 with a pair of doubles.

1949

Manager Burt Shotton and the Dodgers are feted with a ticker-tape parade after winning the 1949 National League pennant.

The Dodgers next faced the Yankees in 1949, after celebrating their National League pennant victory with a ticker-tape parade in Brooklyn a few days before. Unfortunately for the Bums, this contest was significantly more mismatched than the one two years before. Despite an MVP season from Robinson, as well as the addition of the All-Star battery of catcher Roy Campanella and right-hander Don Newcombe, the Dodgers lost four games to one.

In the second game, Robinson scored the only run of the contest after doubling off of the Yanks’ Vic Raschi. Over the course of the remaining four games, Jackie recorded only two other hits. Even though Yankee stars like Berra, Joe DiMaggio, and Phil Rizzuto also struggled, the strength of the Bombers’ rotation allowed them to outlast Brooklyn over the five-game set. “They beat us,” Robinson glumly declared at the end of the series. “They really knocked us down and stepped on us. But I still think we had the better team before the series started.”

Robinson, ever the fiery competitor, was disappointed by the loss, but ready to keep up the fight.

This program from the 1949 World Series can be found on the back wall of the Sports Gallery at the Jackie Robinson Museum. Courtesy of Stephen Wong

Bonus: 1951

Wait, what? You might be thinking: “Didn’t the Dodgers lose the 1951 National League pennant to the New York Giants in a heartbreaking three-game playoff ended by Bobby Thomson’s ‘Shot Heard ‘Round the World’ at the Polo Grounds?” If you are, you would be correct. But the hypothetical 1951 Dodgers-Yankees World Series still exists in our hearts…and on the pages of this never-issued program on display at the Jackie Robinson Museum.

1951 “shadow program” from a World Series that was never played. Courtesy of walteromalley.com

In 1951, Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers held a thirteen-game lead over the New York Giants in the middle of August as the teams were chasing the National League pennant. Then, the Giants began to surge. Led by Bobby Thomson, former Negro Leagues great Monte Irvin, and a largely unknown rookie by the name of Willie Mays, the crosstown rivals won 33 out of their last 40 games and worked themselves into a tie with the Dodgers. In the pre-expansion era, ties for the pennant were resolved in a three-game playoff, which the Giants won. The printer responsible for the programs made two sets: this one, and one for the actual Giants-Yankees series that was played. The unused programs that can be found are popular collector’s items from a past that never was.

1952

The Dodgers returned to the World Series in 1952, this time with home-field advantage. In the first game, they faced off against Yankees ace Allie Reynolds, a 20-game winner that year and runner-up in the American League MVP voting. In the bottom of the second inning, Jackie Robinson smacked a home run to left field, scoring the Dodgers’ first run in a 4-2 victory.

Jackie Robinson hits a home run in the first game of the 1952 World Series.

Their luck didn’t last. Despite a thrilling four-homer performance from Duke Snider and great contact hitting from Pee Wee Reese, the Dodgers eventually fell to the Yankees in seven games. Robinson was befuddled at the plate, striking out looking multiple times (later on, he asked Yankee backstop Yogi Berra if a strike he took in Game 6 was truly in the zone, to which Berra solemnly replied that it was). Indeed, Reynolds and Raschi again stymied the Dodger hitters, while Mickey Mantle recorded ten hits and two home runs against the Don Newcombe-less Dodger pitching staff, including the game-winning shot in the final game.

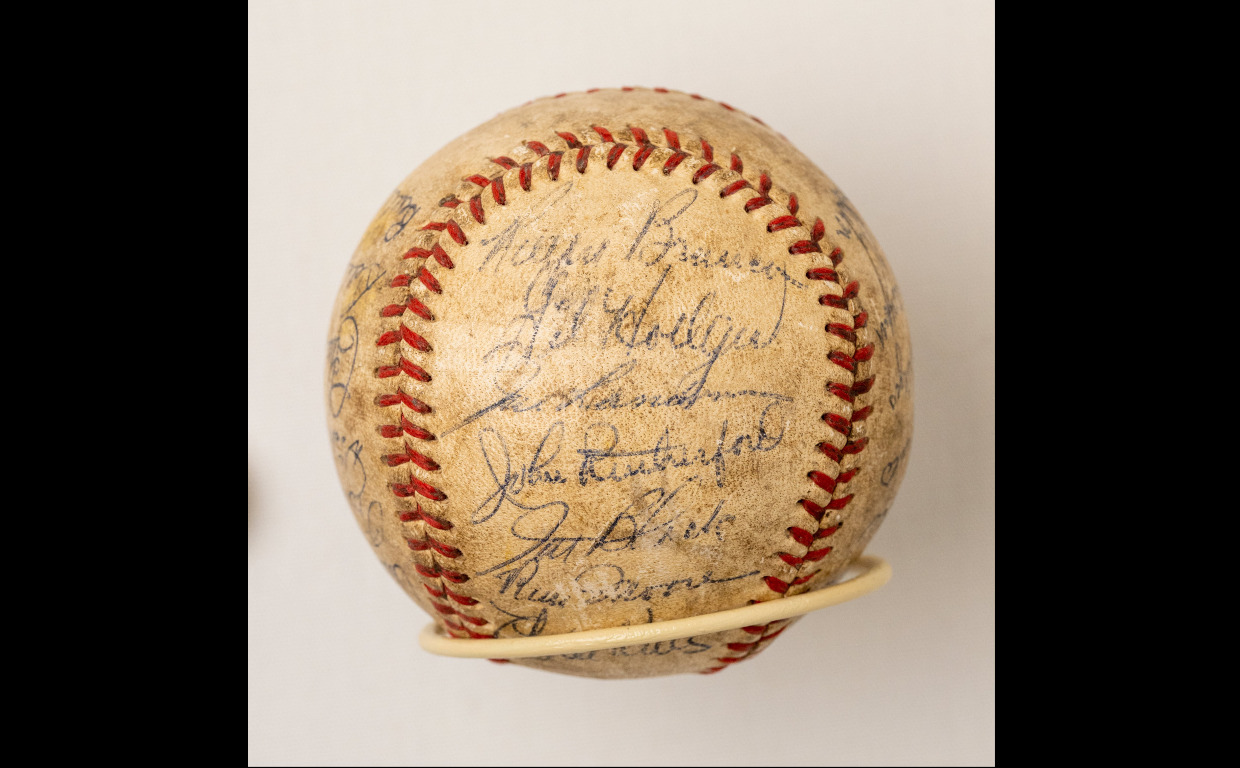

See if you can spot this baseball with signatures from the 1952 Dodgers—it’s located to the left of Pee Wee Reese’s jersey at the Jackie Robinson Museum!

Stay tuned for the second installment of Jackie’s World Series heroics as the present-day Yankees-Dodgers rivalry heads to the Bronx for Games 3, 4, and 5. The Jackie Robinson Museum will be open to the public on Tuesday, October 29 and Wednesday, October 30 as the Dodgers come to town for the Fall Classic!

Although Barry Goldwater’s wide margin of victory didn’t show it, the 1964 Republican National Convention was one of the most contentious and influential moments in modern American politics. It heralded the rise of the modern conservative movement, almost fully marginalized the liberal wing of the Republican Party and severed the last vestiges of Black support for the GOP. Jackie Robinson, a liberal and a special delegate of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, got a firsthand look at the changing face of the party from the convention floor. What he saw and experienced would change his political outlook for the remainder of his life.

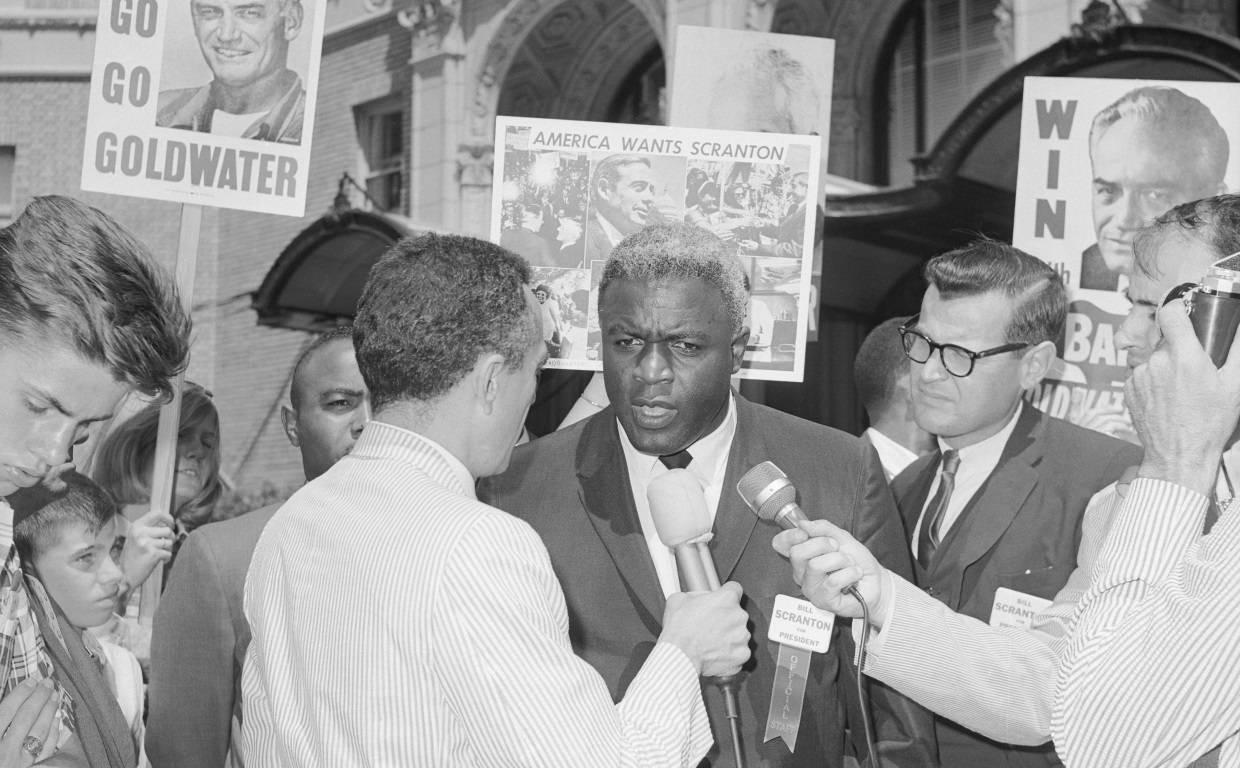

Jackie Robinson speaks to reporters before the convention on July 10, 1964. Getty Images

By the time the party gathered in the sweltering heat of the Cow Palace, an arena near San Francisco, Jackie Robinson had been sounding alarm bells about Barry Goldwater, the presumptive nominee, for months. As far back as August 1963, Robinson warned of Goldwater’s ascendence within the party.1 The Arizona senator was by all accounts a segregationist. He voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act and quickly became the choice of voters who wished to roll back gains on school integration and voting rights.2 Certainly, this was by design. Goldwater and his supporters were fond of declaring that the Republican Party should “go hunting where the ducks are,” courting the votes of those who had opposed the civil rights advancements made under the Kennedy administration.3 For delegates like Robinson, the nomination of Goldwater was unconscionable. It had to be averted at all costs, lest the GOP become, as Robinson bluntly put it in a 1963 Saturday Evening Post article, “for white men only.”4

In 1964, Nelson Rockefeller hired Robinson as a special assistant for community affairs. Here, Robinson joins him at an election night party in 1966, at which Rockefeller was elected to a third term as Governor of New York. Getty Images

Robinson’s ardent opposition to Goldwater had pushed him towards Nelson Rockefeller’s camp over the course of the campaign cycle. Rockefeller, midway through his second term as New York governor, represented the liberal wing of the Republican Party, and had earned Robinson’s favor early in the race. Throughout most of his life, Robinson had identified as a Republican. This in itself was not unusual. For most of the previous three decades, both major U.S. parties had been held together by unusual coalitions, often with wide ideological gulfs between them. The Democrats comprised an alliance between New Deal populists and Southern segregationists, while the Republicans were supported by a diverse range of northern liberals and pro-business conservatives. As a result, Black voters were often torn between two poles, neither of which could be fully trusted to push for racial and economic equality.

In 1960, this ground was shifting. Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy commanded a decisive majority of Black voters, even as Robinson himself supported Republican Richard Nixon, whom he deemed more trustworthy on the issue of civil rights. While many organizers often bemoaned the slow pace of change even after Kennedy was elected, he proved to be more receptive to the demands of the movement than his predecessor had been. By the time he was assassinated at the end of 1963, Kennedy had earned the support and sympathy of much of the Black electorate. A poll conducted shortly after the assassination revealed that eighty percent of Black voters surveyed compared the president’s death to the passing of a close relative. Others feared the assassination would derail civil rights progress.5

Robinson shakes hands with Richard Nixon at a campaign event in 1960. Even by 1963, Robinson had grown wary of Nixon’s changing stances on civil rights.6 “I began to suspect,” Robinson later lamented, “that personal ambition was the dominant drive behind this man.”7 Associated Press

As Robinson entered the Cow Palace in 1964, he remained hopeful that the Republican Party would avoid nominating Goldwater and preserve at least some of its commitments to the still-growing movement. On the floor of the convention, however, his fears quickly materialized. On the second day, Robinson and the other Rockefeller supporters attempted to add a plank to the party platform condemning the extremism of the Ku Klux Klan and the John Birch Society.8 The motion failed, to the raucous applause of a majority of the delegates. As Rockefeller’s bid for the nomination likewise went down in flames, Robinson and his other supporters rallied around the candidacy of Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton. This attempt quickly collapsed as well. Goldwater won the nomination handily on the first ballot.

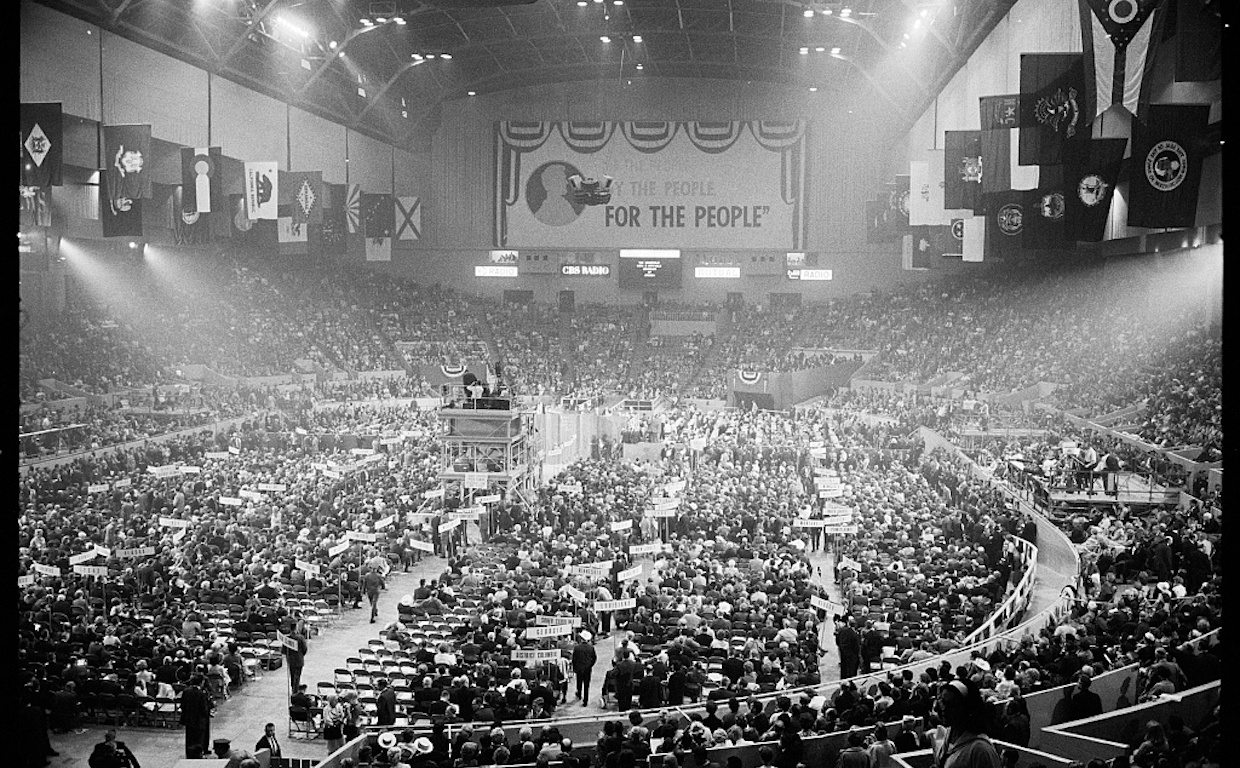

Delegates fill the Cow Palace on July 13, 1964. Wikimedia Commons

Late in the evening, Nelson Rockefeller was finally given a chance to speak. He again denounced the extremism of Goldwater and was drowned out by boos from an agitated crowd.9 Robinson, almost entirely alone in his support, shouted his praise of Rockefeller from the floor. When he did, a nearby delegate rose to confront him. Had it not been for the delegate’s wife holding him back, Robinson later said, they might have come to blows. The other Black delegates, who amounted to just fifteen out of well over a thousand, were similarly mistreated.10

During the convention, churches and labor groups sponsored a civil rights march through San Francisco. Marchers, many carrying anti-Goldwater signs, protested the reactionary politics of the nominee. Library of Congress

Goldwater would go on to lose to Democrat Lyndon Johnson in a landslide that November. For Robinson, the disaster of the convention essentially marked the end of his association with the Republican Party at the national level. Robinson thought he and Black voters had a seat at the table, but they were quickly silenced by a tide of reaction that swept through the convention in 1964. Robinson believed that the Goldwater nomination would signal the permanent demise of the Republicans. Four years later, he would be proven wrong: Richard Nixon, hardened in his opposition to the growing militancy of the Civil Rights Movement, won the presidency four years later with a strategy similar to Goldwater’s.

It was a crushing defeat for Robinson’s political worldview. In the early 1960s, Robinson believed that civil rights victories could be won at the administrative level by ensuring that both major parties would need to compete with each other for Black voters.11 But by the middle of the decade, it became clear that the Republican Party had no interest in winning back the groups whose support had shifted.12 Though Robinson’s belief in the functionality of the two-party system was shaken, he continued to be civically engaged for the rest of his life, fighting to support the candidates he believed would join him in demanding racial and economic justice in the United States.

Click to view this July 10, 1964 interview with CBS 8 reporter Harold Keen.

Robinson strove to be a part of the political process through whatever means were available to him. Whether he was operating inside the system as a convention delegate or campaign surrogate, or outside of it as a protestor or columnist, Robinson understood that the fight didn’t end after the first Tuesday in November. Even so, he never failed to stress the importance of voting rights and political participation to his allies and supporters across the country. As he left San Francisco in 1964, Robinson understood that his defeat at the convention was the beginning of a new era. Robinson’s beliefs had not changed—rather, the shifting alliances of electoral politics were pushing him in new and unexpected directions. As the tumult of the sixties produced both victories and defeats, Jackie continued to rise to the challenge to demand first-class citizenship for all.

The Jackie Robinson Museum remains committed to voting rights across the United States. If you aren’t registered to vote, please visit vote.gov to register prior to Election Day on November 5, 2024 (deadlines vary by state). Visitors to the Museum can access this site from a kiosk located near the lobby, immediately behind the elevator.

References

[1] Jackie Robinson, “Jackie Robinson Says: Has Goldwater Taken Over For the GOP?,” Michigan Chronicle, August 10, 1963, sec. Editorial Page.

[2] Leah M. Wright, “Conscience of a Black Conservative: The 1964 Election and the Rise of the National Negro Republican Assembly,” Federal History 1 (2009): 32.

[3] Stewart Alsop, “Can Goldwater Win in 64?,” Saturday Evening Post, August 8, 1963.

[4] Jackie Robinson, “The G.O.P.: For White Men Only?” Saturday Evening Post, August 10-August 17, 1963

[5] Sharron Wilkins Conrad, “More Upset Than Most: Measuring and Understanding African American Responses to the Kennedy Assassination,” American Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2023): 279–307.

[6] Jackie Robinson, “An Open Letter To Dick Nixon,” New York Amsterdam News, May 4, 1963.

[7] Jackie Robinson, “Did Goldwater Promise Nixon?,” New York Amsterdam News, November 21, 1964.

[8] “In The High Drama Of Its 1964 Convention, GOP Hung A Right Turn,” All Things Considered (NPR, July 10, 2014), https://www.npr.org/2014/07/10/330496199/in-the-high-drama-of-its-1964-convention-gop-hung-a-right-turn.

[9] Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York, Putnam, 1972),

http://archive.org/details/ineverhaditmade00robi.

[10] Wright 2009, 35

[11] Jackie Robinson, “Negroes Know Their Enemies,” New York Amsterdam News, February 24, 1962, see also “Baseball Great Jackie Robinson Talks about Politics in San Diego in the 1960s” (CBS, July 10, 1964), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WaRk0-OEUKg.

[12] Alsop, “Can Goldwater Win in 64?”

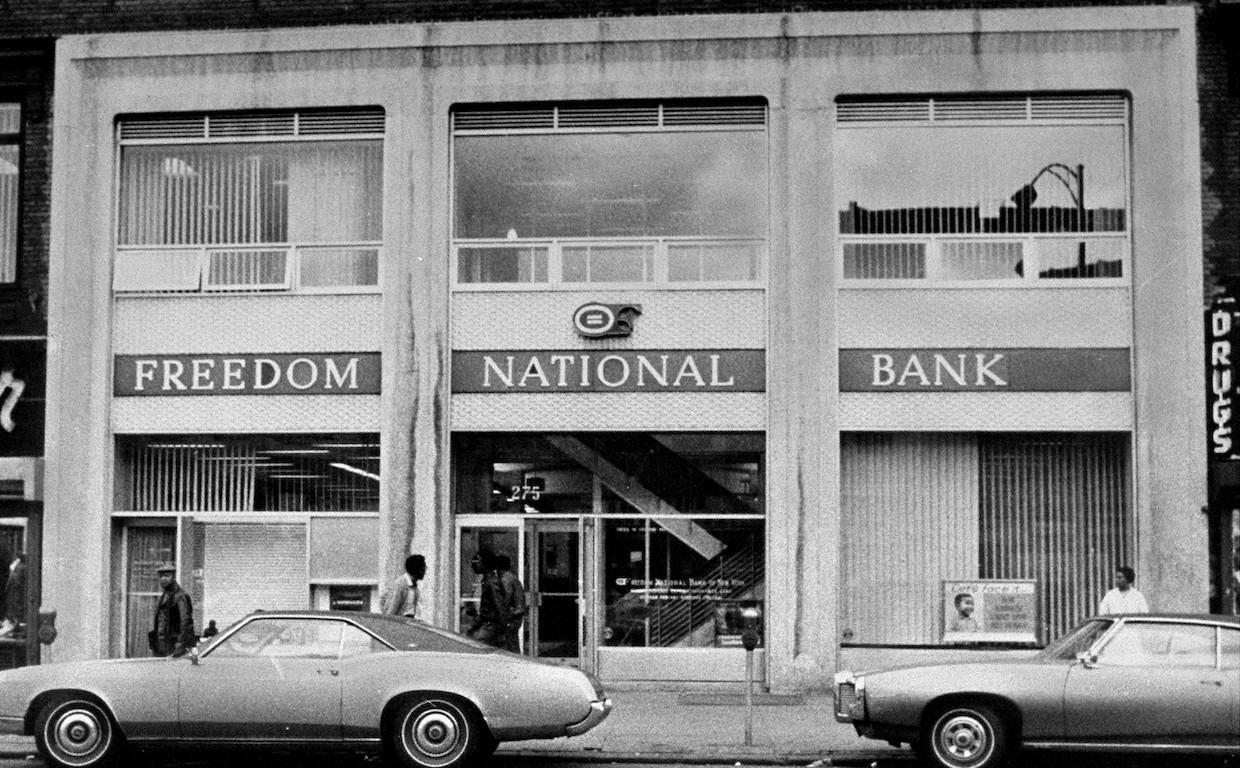

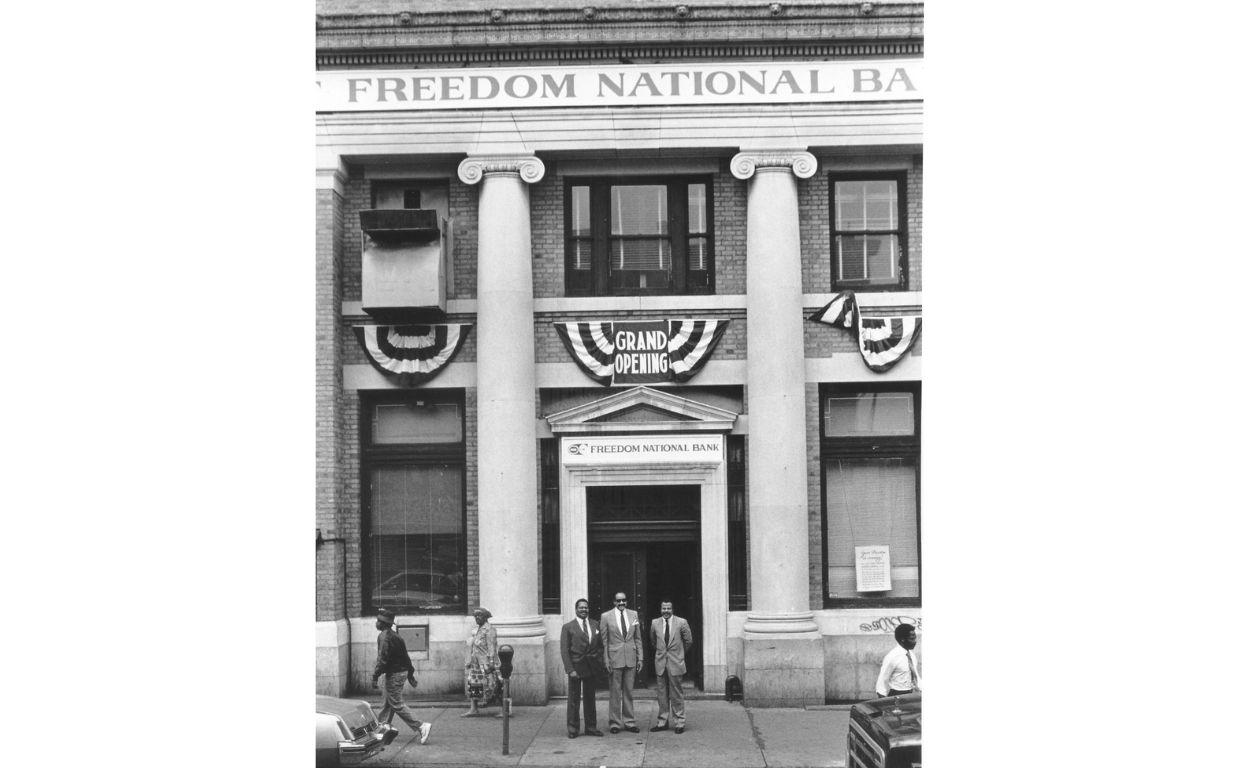

What can a bank mean to a neighborhood? To its depositors and borrowers, Freedom National Bank was a local financial institution not unlike thousands of others across the United States. But to many Black residents in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant, it was also a source of immense pride. From 1964 to its closure in 1990, Freedom National stood at the center of 125th Street in Harlem, providing access to banking services that many residents had previously been denied their entire lives. Jackie Robinson, who was the first chairman of its board of directors, worked tirelessly to ensure that its operations were not only a financial success, but that it was expanding access to loans and other services for Black communities across the city. Although the bank caused him incredible worry and many nights of lost sleep, it was a poignant example of his decades-long struggle for Black America’s economic progress and independence.

Main branch of Freedom National Bank on 125th Street in Harlem, 1970. Getty Images

In 1963, Dunbar McLaurin, a Black Harlem businessman, had begun to lay the groundwork for opening a bank in Harlem. He had dreamed of doing so for many years, but only by the peak of the Civil Rights Movement were his plans coming to fruition. It was a needed resource: African Americans had long struggled against banks refusing to loan to them due to economic dispossession as well as racist perceptions of Black borrowers as untrustworthy, inequities that continue to exist today. While means of discrimination have become more complex and technologized in the years since, McLaurin was confronting an issue that economists and activists are yet dealing with in the present: keeping money in New York’s Black communities.

Jackie Robinson speaks to reporters at the grand opening of Freedom National Bank, WGBH.