News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Admission is free on April 15 for Jackie Robinson Day.

On April 15, Jackie Robinson crossed the foul lines of Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field and took up his position at first base. As he did so, he became the first Black major league player since 1884, ending the secretive, league-wide “gentlemen’s agreement” among team owners to refrain from hiring Black ballplayers. It was Robinson’s first step in a ten-year major-league journey that would include a Most Valuable Player award, six National League pennants, and a World Series ring. But when Robinson stepped into the batter’s box and faced the dizzying curveballs of the Boston Braves’ Johnny Sain, he was just number 42, trying to make good on baseball’s biggest stage.

Robinson’s debut received a wide range of reactions in the press: The local white dailies in New York seemed largely indifferent, with some papers not even bothering to mention Robinson at all. In Black newspapers across the country, however, Robinson’s promotion to the Dodgers and first games in Brooklyn were front-page news as photographers and reporters celebrated his arrival and prognosticated about his future with the team. Robinson knew he was making history that day. He also understood that there would be a long road ahead.

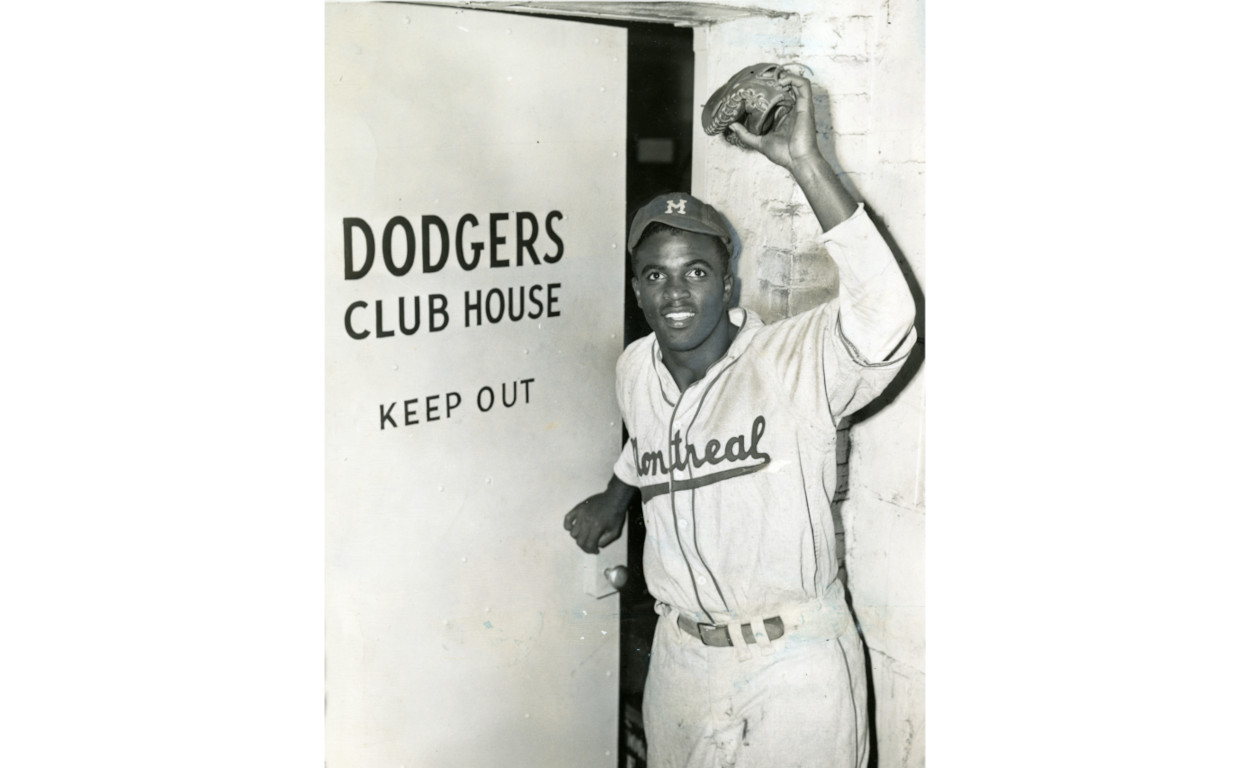

Jackie Robinson enters the Dodgers clubhouse on April 11, 1947 after the team purchased his contract from the Montreal Royals. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

By the final weeks of Spring Training in 1947, Jackie Robinson’s promotion from the Montreal Royals minor league squad to the Dodgers was not certain. Though he had a remarkable season in 1946, he had a difficult spring in Panama and Cuba, battling Jim Crow accommodations and stomach illnesses as he tried to make the team. As the teams headed north, Robinson still remained formally a member of the Montreal Royals.

Prior to Opening Day against Boston, the Dodgers played four exhibition games, one against their Royals farm club and three more against the Yankees. On April 10, the day of the first game, Robinson’s contract was formally purchased by the Dodgers, elevating him to the major league squad. The series drew almost 100,000 fans across the games, close to double the previous season’s exhibition total. “Robinson is the attraction,” declared Wendell Smith, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier and a close confidant of Jackie. “There is no doubt that Negro fans are showing their appreciation by digging down and coming up with money for tickets every day.”1 Even before the official start of the season, it was clear that Robinson would be a major draw.

Soon, it was time for Opening Day. As Jackie prepared for the game, his wife Rachel and infant son Jackie Jr. began their journey from their temporary home at the McAlpin Hotel in Herald Square to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Not wanting to get lost on the subway, Rachel tried in vain to hail a cab. Most turned her down. Whether it was because of the distance, Rachel and Jackie Jr.’s race, or some combination of both, she wasn’t sure. But eventually, she was able to get to the stadium in time to see Jackie play.

Rachel and Jackie Jr. join Ruth Campanella (left) at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947. Rachel enlisted the help of a hot dog vendor to warm Jackie Jr.’s bottle of milk. Jackie Robinson Museum

The Dodgers opened the 1947 season against the Boston Braves in front of a crowd of about 25,000 fans. Robinson batted second, between second baseman Eddie Stanky and center fielder Pete Reiser. Just as he did in the exhibition games, Robinson played first base that day, taking his position in the infield alongside Stanky, Dodger stalwart Pee Wee Reese at short, and fellow rookie Johnny “Spider” Jorgensen at third. First base was a new position for Robinson: He played primarily middle infield positions in college and with the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs, and spent most of the previous season in Montreal at second base. Even so, he performed exceptionally, going a perfect 11-for-11 in the field.

At the plate, though, Robinson was less successful. He was up against Boston’s Johnny Sain, a fiery curveballer who would go on to win 21 games that year. In his first trip, Robinson grounded to third for the second out of the first inning. In the bottom of the third inning, Robinson flew out to left, ending a 1-2-3 frame. In the fifth inning, with runners on the corners and one out, Robinson lashed a dribbler through the box that looked like it would be his first career hit and run batted in.2 Instead, Boston shortstop Dick Culler snagged the grounder, flipped it to the second baseman, who spun and threw to first, beating Robinson by a hair for an inning-ending double play.

Robinson faced Sain once more in the bottom of the seventh, with none out and the Dodgers down 2 to 3. After Eddie Stanky drew a walk, Robinson laid down a stellar sacrifice bunt, a scrappy move that would come to define Robinson’s style of play for a decade. A wild throw to first allowed Robinson to advance a base, and by the time the ball was returned to the infield, Stanky had checked in at third as well. Pete Reiser came to the plate next and immediately lashed a double to right, scoring both Robinson and Stanky and giving Dem Bums a 4–3 lead. Two batters later, Gene Hermanski scored Reiser with a sac fly, extending a lead that would be preserved for the rest of the game.

As far as debuts go, it was a far cry from Robinson’s four-hit, four-run performance in his first game in the minor leagues. Despite making history, Robinson barely made a splash in the white press: When New York’s sportswriter class sat down in front of their typewriters to summarize the game in the next morning’s dailies, Robinson was almost completely overshadowed by Reiser’s clutch hitting and the number of empty seats in the park that day. In Dick Young’s article in the April 16 New York Daily News, one of the city’s premier outlets for sports at the time, the historic import of Robinson’s debut wasn’t mentioned at all.3 Red Smith, of the New York Herald tribune, offered a summary of Robinson’s performance late in his article, but he, like Young, was far more interested in the suspension of Brooklyn’s popular manager, Leo Durocher, on account of his associations with known gamblers.4 In all, Robinson was mostly overlooked by these reporters, though given the immense pressure under which he was performing, he may not have paid it any heed.

Jackie Robinson clutches a newspaper as he walks away from Ebbets Field after his April 15, 1947 debut. Getty Images

The response in the Black press was markedly different. Not only was Robinson covered extensively, his debut was front-page news in the Pittsburgh Courier, Baltimore Afro-American, and Chicago Defender. Because of the publication schedules of the Black weeklies (they typically published on Saturdays), Robinson’s debut was not covered until the April 26 editions of most papers, with the April 19 editions focusing primarily on the exhibition contests.

The delay didn’t dampen the effusive support. Large photo spreads highlighted Robinson’s actions before and after the game, and commentators offered predictions for the season and advice to fans. The Courier even ran a series of photos detailing the process of assembling the Robinson story for the newspapers’ readers.5 It is important to remember that Robinson’s debut itself was a triumph for the Black press: Wendell Smith of the Courier and Sam Lacy of the Afro-American played key roles in fighting for the desegregation of baseball. While the journalists and editors understood that Robinson’s (and Black America’s) fight against inequality and mistreatment in the twentieth century was still getting started, the pages of the weekly papers were a forum for communities to celebrate the progress that was being made.

Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier. Getty Images

The support wasn’t limited to the newspapers, either. Most sources reported that there were plenty of Black fans in the stands both during the exhibition series and the day of Jackie’s debut. The Sporting News estimated that 14,000 of the fans at the ballpark were Black.6 They made their voices heard too: Dixie Walker, a popular Dodger outfielder who had circulated a petition during the spring threatening to lead a strike if Robinson was promoted to the team, was greeted with a chorus of boos whenever he stepped to the plate. The support for Jackie persisted after the games as well. When Robinson left the stadium, he was mobbed by well-wishers, just as he was the year before as a breakout star in Montréal.

Back at home at the McAlpin in Manhattan, Robinson took his struggles at the plate that day in stride. “It was just another ballgame, and that’s the way they’re going to be,” he remarked to Ward Morehouse of the Sporting News.7 “I’m sticking to my style of playing ball…I like to meet the ball and hope a lot of them fall safe.” Robinson knew that Branch Rickey and the fans had faith in Robinson to make the grade as a major league ballplayer. There were 153 games left to play, and there was no point in dwelling on the first one.

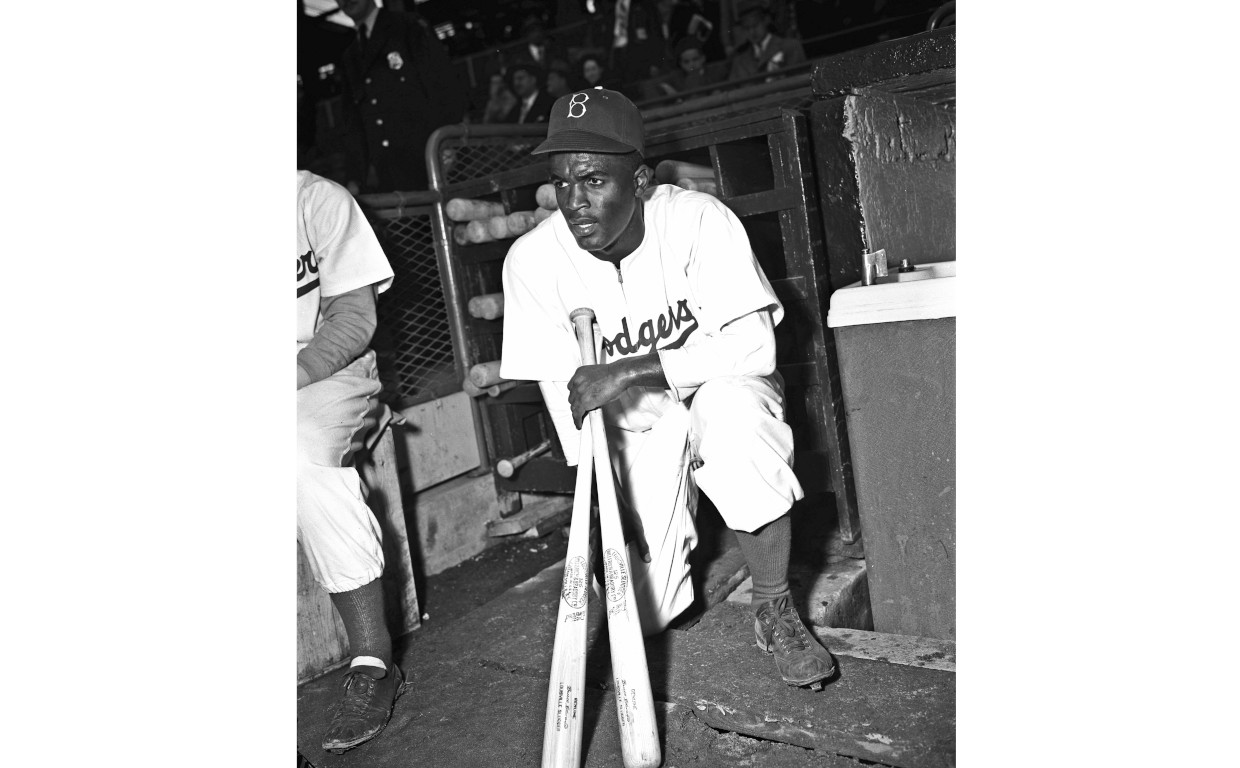

Jackie Robinson observes the action on the field from the steps of the Dodgers’ dugout on April 15, 1947. Getty Images

Indeed, Robinson had a long way to go. Throughout his first season, he endured racist taunts, pitches thrown at his head, and opponents attempting to spike him on the basepaths. Despite the incredible adversity he faced, Robinson amassed a .297 batting average and lead the league in stolen bases and sacrifice hits. In September, he won the inaugural Rookie of the Year award, affirming his skill as a contact hitter and baserunner. Robinson could not have possibly imagined that his debut would be honored each year in ballparks across the country. Neither, it seems, did many of those who covered his first day in the major leagues. But for many of the fans in attendance, and the Black newspapers that followed his every move, history was being made that is still celebrated to this day.

News

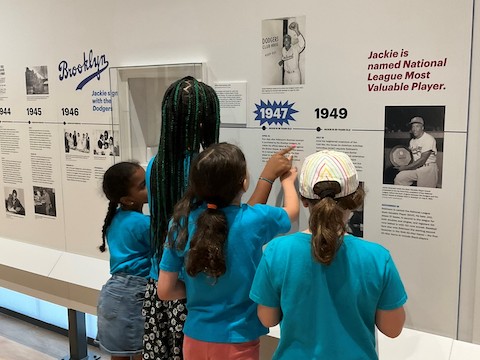

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE