News

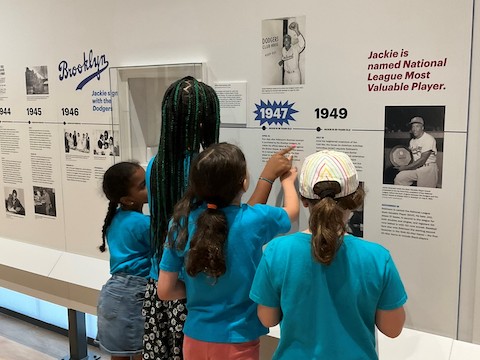

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today!

On January 22, 1957, copies of Look magazine flew off the shelves at newsstands around the United States. The reason for the excitement was no mystery: Look had scored a huge sports scoop. After ten years with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Jackie Robinson was announcing his retirement from baseball. The brief story—only two pages long—appeared at the end of the magazine with little fanfare beyond a small press conference. The story touched off a wave of furor, as team executives and journalists accused Robinson of disloyalty to the game and the press. However, by leaving baseball on his own terms, Robinson used his retirement to secure financial stability for his family in the years to come.

Jackie Robinson waves to photographers and journalists as he exists the Dodgers clubhouse for the final time. Getty Images

By the end of 1956, Jackie knew that his journey in baseball was coming to a close. Even so, he had performed effectively during the Dodgers’ ‘56 campaign and suggested that he was ready to return the next year. His .275 batting average was 21 points better than the year before, and his clutch hitting in the World Series that year kept the Dodgers in contention until their Game 7 blowout loss. Though his competitive spirit still burned, Robinson, now 38 years old, knew it would soon be time to hang up his spikes. His financial advisor, Martin Stone, had been searching for career opportunities for Robinson for a few years. By the beginning of December 1956, Robinson was in talks with Chock full o’ Nuts, a New York coffeeshop chain, to serve as vice president of personnel. Having secured a contract with William Black, the owner of Chock, Robinson’s exit from baseball was all but assured.

Jackie greets workers at a Chock full o’Nuts restaurant in March 1957. Getty Images

Robinson’s retirement, however, needed to be kept a secret. Years earlier, he had signed a contract with Look magazine for $50,000 over two years, offering the Iowa-based publication the exclusive rights to the story. The job at Chock (an executive position placing him in charge of the chain’s foodservice personnel) would pay $30,000 a year—a number comparable to the salary he expected to make with the Dodgers in 1957. Though the contract was inked, the plan was to not announce the position until Look went to print.

While Robinson was getting his affairs in order, the Dodgers threw him a curveball in the middle of December: Robinson was traded to the New York Giants. Robinson was dealt to the Dodgers’ crosstown rival for $35,000 and Dick Littlefield, a journeyman pitcher of middling talent. The blockbuster deal (and the suggestion that Robinson stood to make over $50,000 from the Giants in 1957)1 indicated that even at 38, Jackie still had big league talent. As Robinson finalized his plans, he begged the two baseball organizations to keep the deal a secret.2 They refused.

Rachel, David, and Jackie hold Giants ephemera at their Stamford, Connecticut home, December 1956. Associated Press

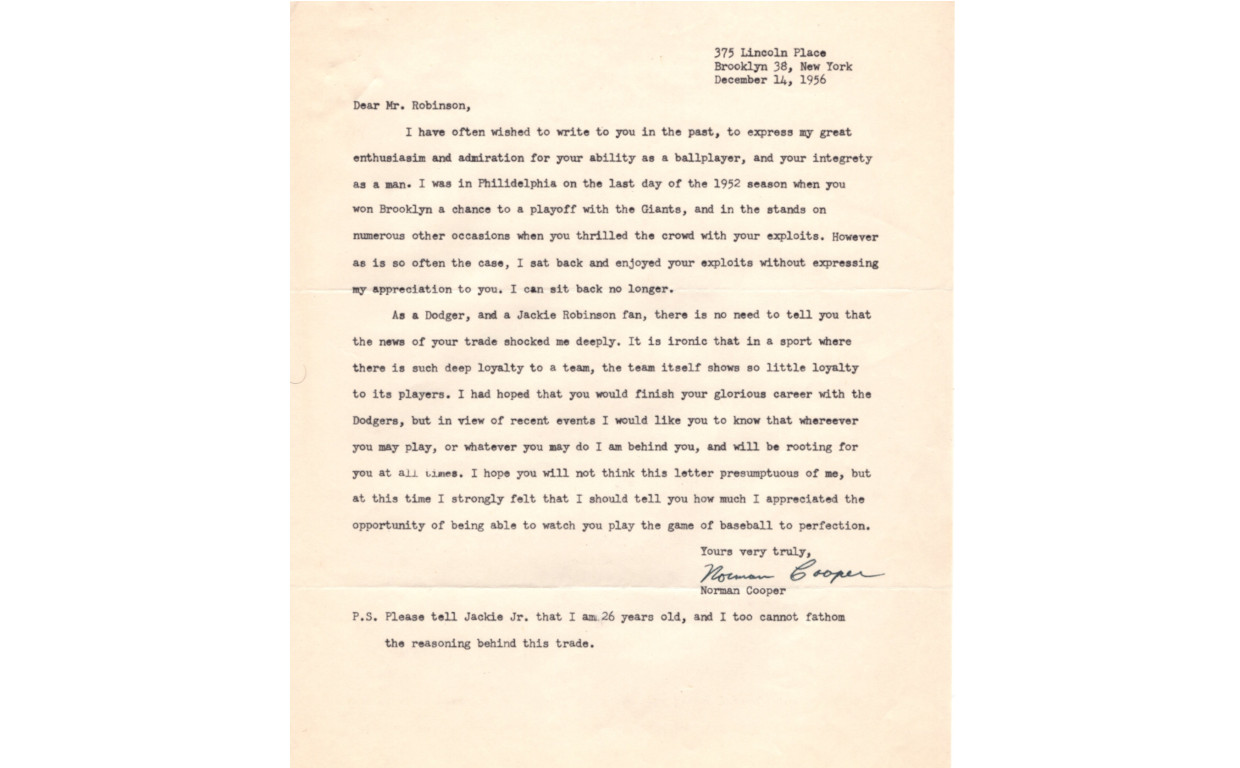

Immediately, the Dodger office on Montague Street was deluged with hate mail. For ten years, Robinson had been the face of the Dodgers. A trade (to a hated rival no less!) was unimaginable. “Sometimes I suspect that all of you in the organization” an anonymous letter-writer offered, “would sell your grandmothers to the Green Bay Packers if you could turn an honest dollar doing so…I suggest that you also trade all your other standbys…[T]hink of all the money you could make.”3 Robinson got letters of support from Brooklynites as well: “It is ironic,” said a local Brooklyn fan, “that in a sport where there is such deep loyalty to a team, the team itself shows so little loyalty to its players.”4 Other letter writers expressed hope that Robinson would simply retire rather than play for the Giants.5 Those fans would get their wish.

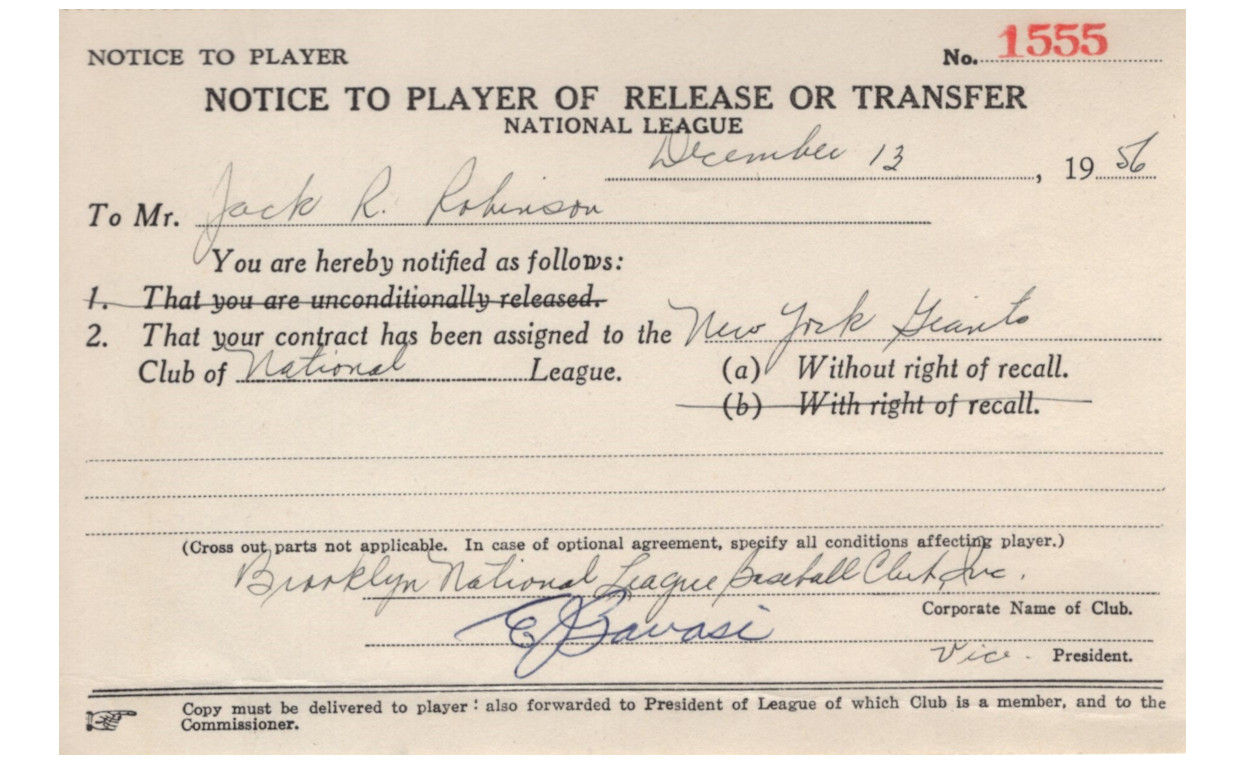

Notice of Transfer given to Jackie Robinson informing him of his trade to the New York Giants. Buzzie Bavasi’s signature appears at the bottom. Jackie Robinson Museum

By the first week of January, Robinson’s secret was out. Even before Lookwent to print, the story leaked, setting off a new wave of vitriol. This time, however, much of it was directed at Jackie, and it came from an expected source: Dodgers management itself. Soon after it became apparent that Robinson had sold the story to a newsmagazine, Buzzie Bavasi, the team’s general manager, took a swipe at Robinson in the press. “That’s typical of Jackie,” he scoffed. “Now he’ll write a letter of apology. He’s been writing letters of apology all his life.”6 Bavasi went on to accuse Jackie of betraying the New York sportswriters who had been covering him for the previous ten years.

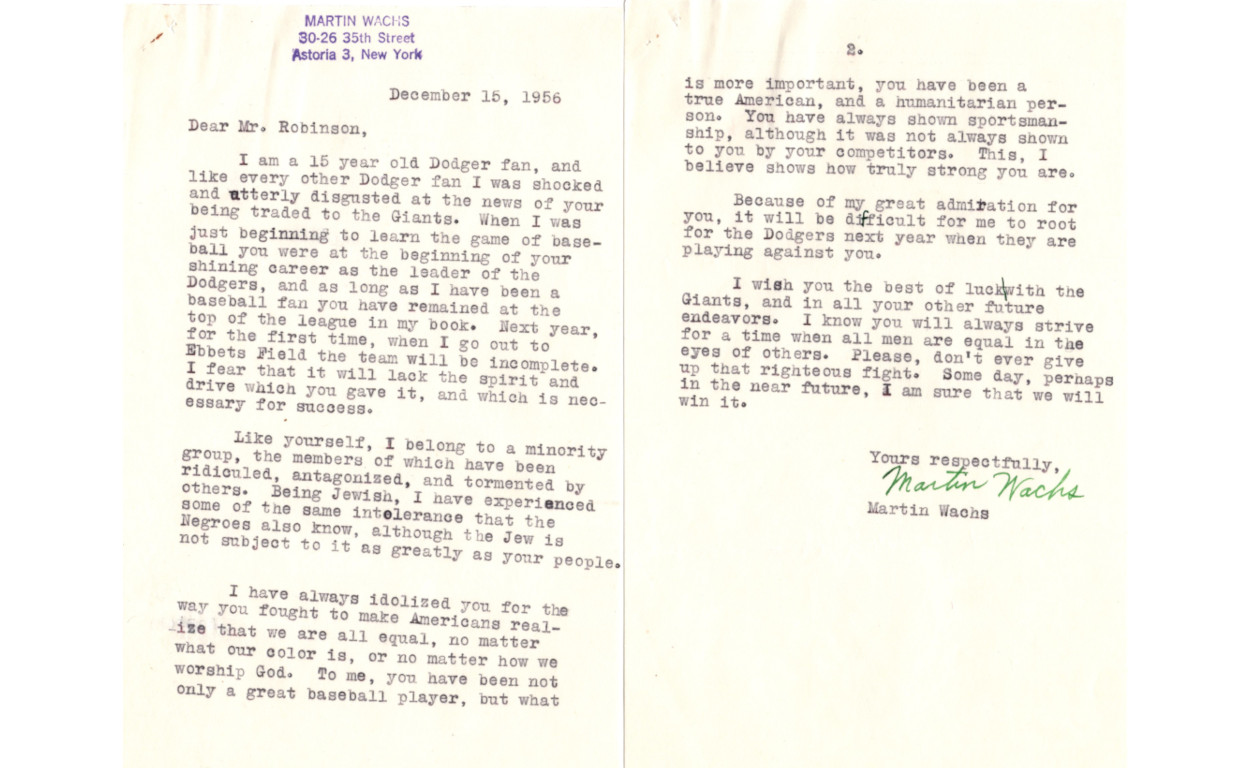

A letter from Martin Wachs, a young Dodger fan bemoaning the trade to the Giants. Jackie Robinson Foundation

Letter from Norman Cooper decrying the Dodgers’ disloyalty to Robinson. Jackie Robinson Museum

Robinson was taken aback. While his relationship with Bavasi had been at times stormy over the previous half-decade, Robinson was particularly incensed by Bavasi’s comments. “After I read what Buzzie Bavasi said, I wouldn’t ever play again,” he declared.7 The trade was null and void. Littlefield and the $35,000 returned to the Giants and Robinson began to settle into his life as a business executive.

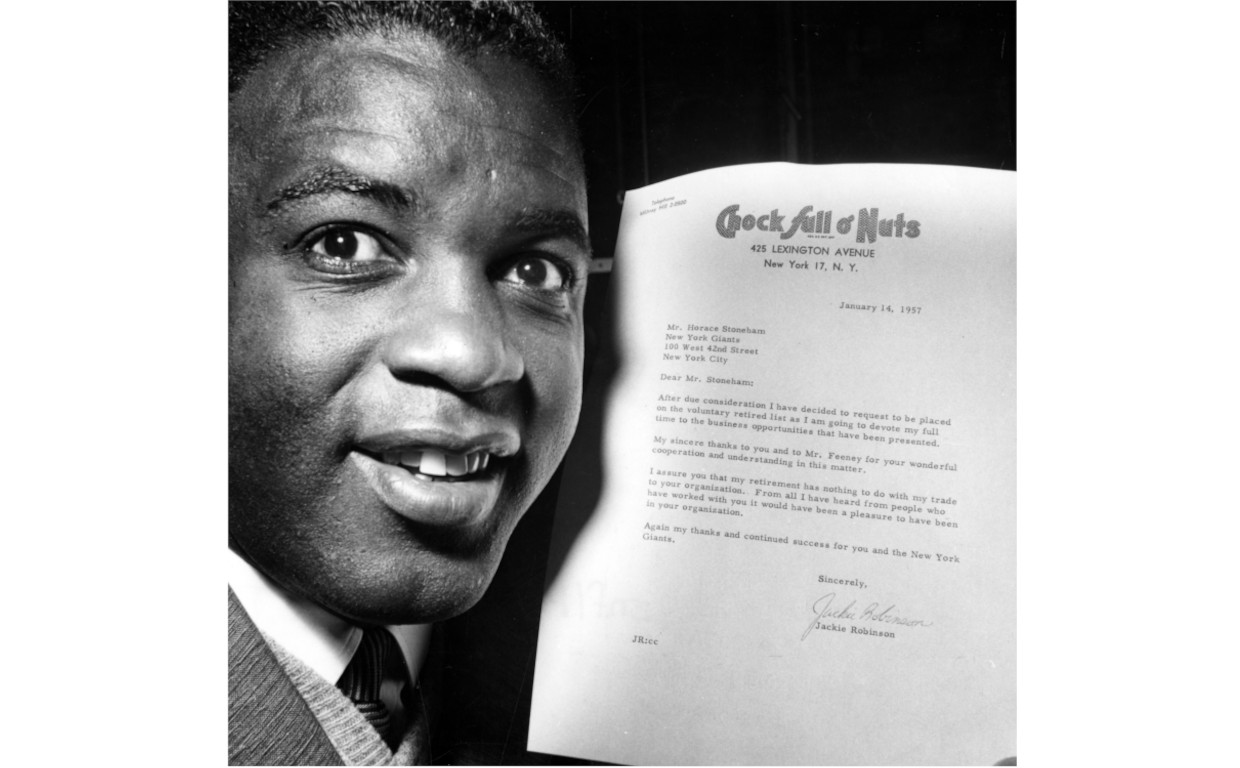

Jackie Robinson holds up a letter informing Giants owner Horace Stoneham of his retirement. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

His retirement was hotly debated in the press: Though many New York writers assailed Robinson’s decision to sell his retirement story, it earned him plenty of defenders across the country as well. “Perhaps it is small townish of this writer to take such a stand,” wrote Marvin E. Miller of the Lancaster, Pennsylvania Daily Journal-Intelligencer.8 “But we cannot…understand how any sportswriter can figure an athlete owes him anything.” John Hanlon, writing in a Providence, Rhode Island newspaper, went so far as to say that the sportswriters owed him: “His story always sold,” Hanlon said, referencing Robinson’s willingness to opine to the press over ten years with the Dodgers.9 “He was not only bread and butter to the reporters’ daily menu, but frequently their steak and wine, too.” Across the country, weekly columns and letters to the editor praised Robinson for leaving the game. Rachel Robinson saved many of these positive responses in the family scrapbooks.

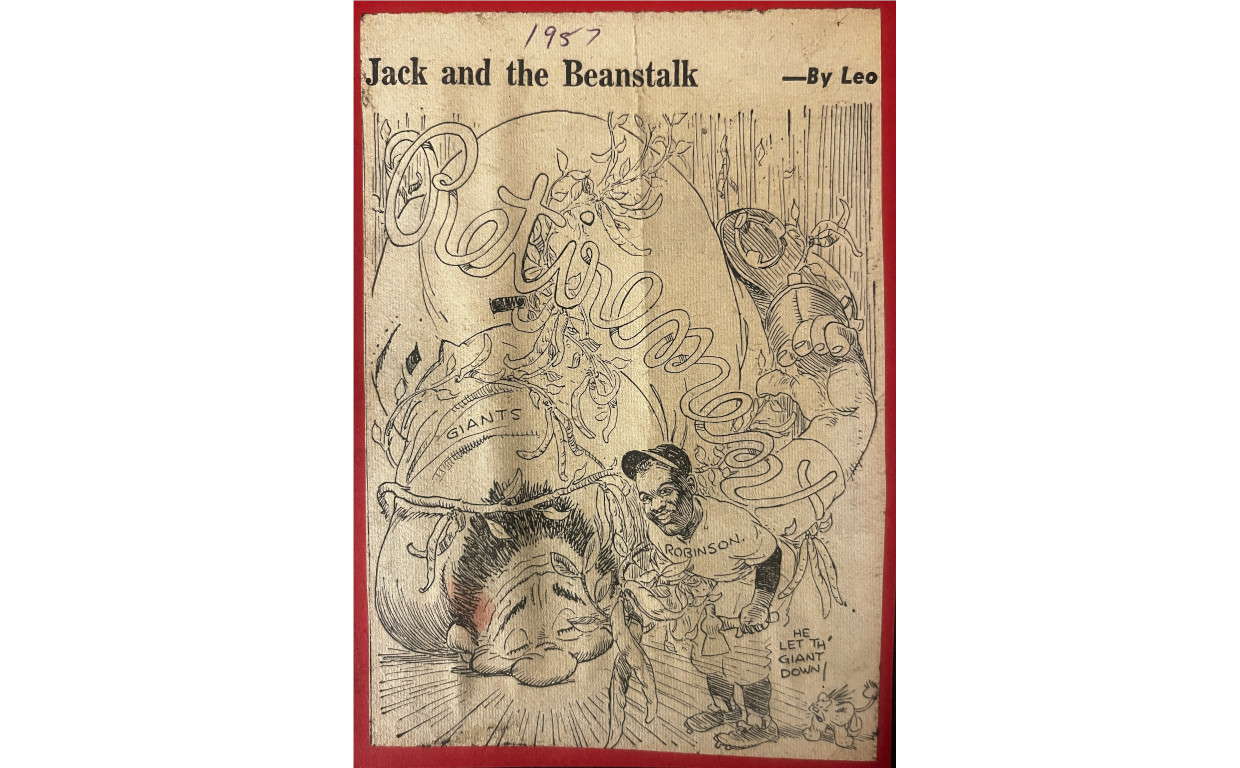

A cartoon by Leo O’Mealia in an early 1957 edition of the New York Daily News. A smiling Jack(ie) Robinson, holding a hatchet, has cut down the beanstalk, causing the New York Giant to crash to the earth. Rachel Robinson Scrapbooks, Jackie Robinson Museum

Jackie, for his part, was pleased with his decision. “Personally,” Robinson later wrote in his autobiography in 1972, “I felt that Bavasi and some of the writers resented the fact that I outsmarted baseball before it outsmarted me.”10 Robinson was able to leave baseball by his own choice and start a lucrative career outside of it. In his era, few players were able to say the same.

Building a career outside of baseball was always important to Robinson. When he was promoted to the Dodgers at age 28, he knew that his career in baseball might not be long. As early as his rookie season, he would often say that he only expected to be in baseball for three years.11 Keen to realize financial security outside of the game, Robinson sought out a diverse range of business opportunities during his post-baseball career. The business knowledge he was able to gain during the winter months between seasons allowed him to transition smoothly into his job at Chock, which he held until 1964.

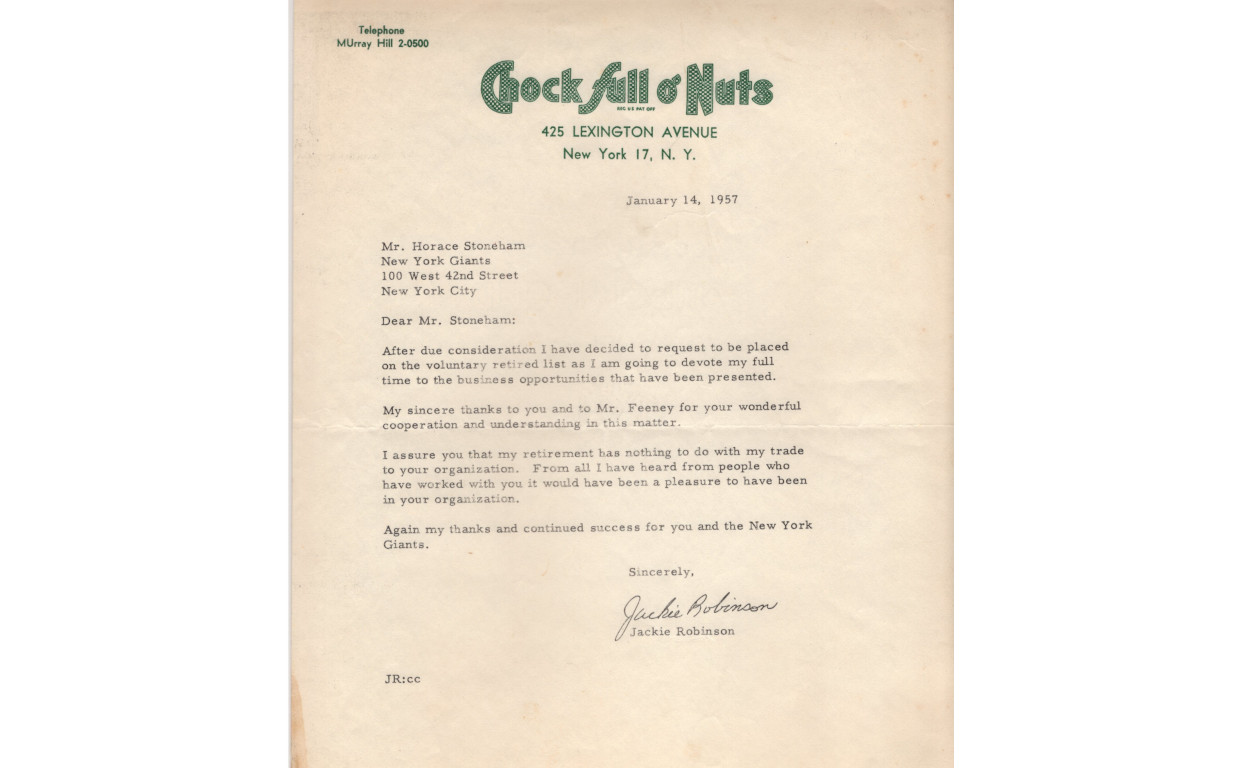

Letter from Jackie Robinson to Giants owner Horace Stoneham. Robinson, writing on Chock stationery, requested to be placed on the voluntary retired list, confirming his exit from baseball. Jackie Robinson Museum

As for the Look story itself, it was brief and to the point. Robinson confirmed to his readers that his trade to the Giants did not influence his decision to retire.12 He continued by recounting the things he would miss about baseball: his teammates, the fans, and even the umpires with whom he often feuded. He apologized to the reporters who had hounded him over his decision to honor his contract with Look. Finally, he ended on a personal note, describing how his sons Jackie Jr. and David burst into tears over his retirement from baseball; his daughter Sharon, for her part, was excited that her father would be home more often. “It’s tough for a 10-year-old to have his dad suddenly turn from a ballplayer into a commuter,” Robinson concluded. “But someday Jackie [Jr.] will realize that the old man quit baseball just in time.” Indeed, Robinson left baseball on his own terms. His exit from the game opened doors for him both in business and the growing struggle for civil rights. As he moved through life beyond the confines of Ebbets Field, he was finally able to do so as his own man.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE