News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Get your tickets for January Programs & Events!

The revolutionary year of 1968 opened new fronts for political struggle in the United States and around the world. Protestors, many of them students, rallied for women’s rights, racial and economic equality, and an end to the escalating Vietnam War. Black athletes joined the struggle by seeking new ways to leverage their fame and political capital to demand global change. As the Olympic Games in Mexico City neared, many athletes began to discuss the possibility of boycotting them to protest racial injustice in the U.S. and in South Africa.

(l to r) Peter Norman, Tommie Smith, and John Carlos stand on the podium after the 200m finals at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Getty Images

Jackie Robinson took the bold stance to support the athletes in their fight. He published columns, sent letters, and circulated protest materials on the athletes’ behalf. Although the boycott itself did not come to fruition, it was nonetheless successful in achieving one of its most important goals: keeping apartheid South Africa off of the international stage. The boycott revealed deep political and tactical divides between generations in a changing movement, many of which have echoes to the present day.

Button for the Olympic Project for Human Rights owned by Tommie Smith, National Museum for African American History and Culture

The plan to boycott the Olympics was hatched in late 1967 by Dr. Harry Edwards and a handful of Black athletes on the West Coast.[1] In October, they chartered the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) to coordinate their activities. Word spread rapidly. As more athletes expressed interest, a set of demands began to coalesce by December. First, OPHR demanded that Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight title and right to box be restored (they were both stripped in retaliation for his refusal to be drafted in the Vietnam War). Next, they called for the firing of Avery Brundage, the notoriously racist president of the International Olympic Committee. Third, they demanded that Black coaches and administrators be added to the U.S. Olympic apparatus. Fourth, they demanded the exclusion of South Africa from the 1968 games. Finally, the athletes called for a boycott of the New York Athletic Club on account of its racist and exploitative policies.

Avery Brundage served as president of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. Wikimedia Commons

A day after the demands were made public, Jackie Robinson’s “Home Plate” column appeared in the New York Amsterdam News. “My first reaction was this: I was opposed to it,” Robinson said of the boycott in his column. “Later in the day, however, I began to give the matter some careful thought…I was not so certain [it] was a bad idea.”[2] Three weeks later, Robinson affirmed his support: “Black athletes should resolve to stand squarely behind the Olympics boycott,” he said, in a column offering a list of resolutions for the new year.[3]

Soon enough, opposition materialized. Boycotters received torrents of racist hate mail as well as admonishments from older Black civil rights figures. A.S. “Doc” Young, a popular sports columnist for Ebony, smeared the boycott in the pages of the Chicago Tribune.[4] Jesse Owens, who had humiliated Hitler’s theories of white supremacy three decades earlier with his gold medal at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, likewise advised against a boycott, as did Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP. The planned boycott revealed a growing generational split in the movement: Edwards and the young Olympians, disappointed by the slow progress in American society since the middle of the decade, were ready to take action. Meanwhile, many retired athletes and established civil rights figures attempted to push back, citing the boycotters’ demands as unrealistic. Though he initially had his reservations, Robinson was impressed by the boycotters’ bravery, and chose to lend his support.

Robinson was not drawn to the movement merely by the boycotters’ youthful energy: he shared their disgust with the New York Athletic Club, and had been an enemy of the NYAC’s segregationist stance for years. Black athletes could compete at the club’s track meets (generating thousands of dollars in revenue) but could not be members of the club themselves. In 1962, Robinson and an Amsterdam News reporter sent telegrams to a number of Black athletes urging them not to compete at the NYAC meet at Madison Square Garden.[5] While their words went unheeded that year, by 1968, pressure to boycott the club’s meet was growing. OPHR, ready to test its organizing capabilities, was primed to take swift and decisive action. After a flurry of letters and calls from OPHR members (and another column from Jackie admonishing those who still chose to participate), Black athletes and schools dropped from the roster and attendance plummeted.[6] NYAC’s 1968 Garden meet was a disaster.

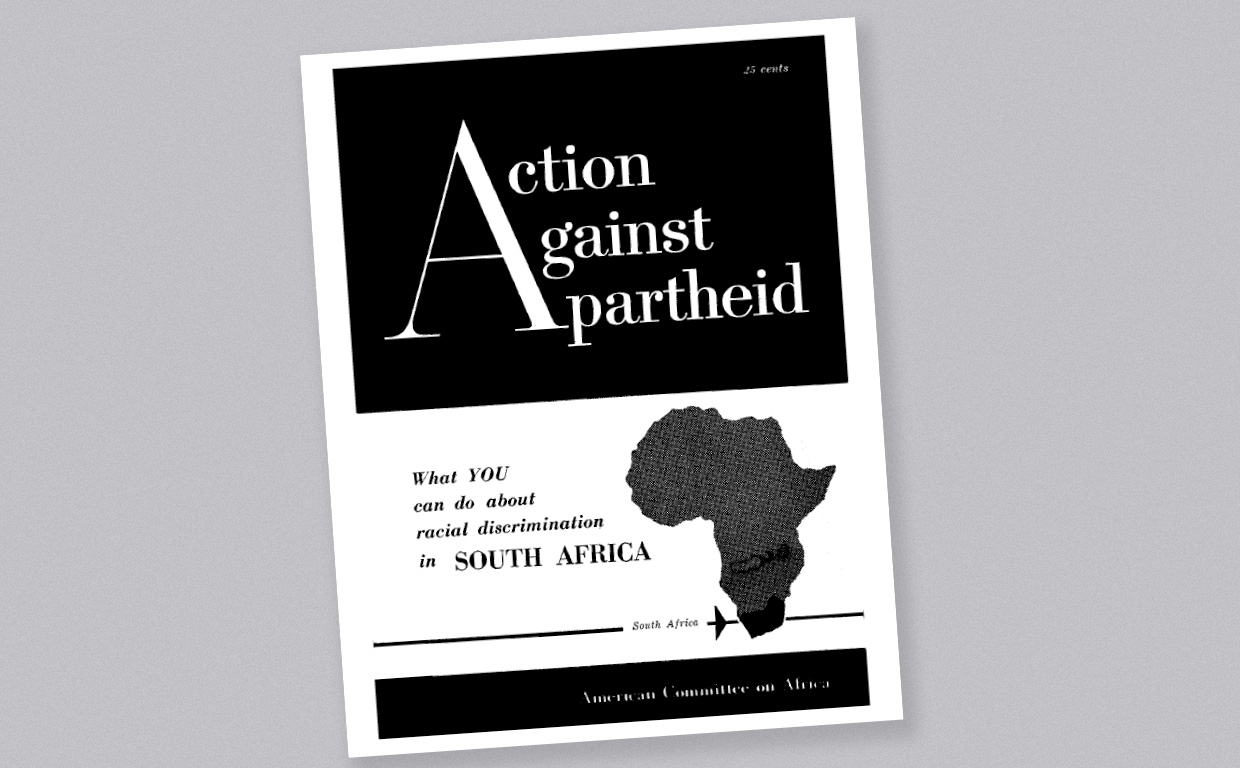

A pamphlet by the American Committee on Africa, 1960

In 1960, Jackie Robinson served as the honorary chairman of the American Committee on Africa’s Emergency Conference after the Sharpeville Massacre, in which South African police killed dozens of protestors demonstrating against apartheid.

Robinson also saw an Olympic boycott as a tool to fight against the apartheid regime in South Africa. Over a century after the Southern Cape’s colonization by Dutch and British settlers, native Africans still lived under deplorable economic conditions and lacked political representation. Knowing that putting the spotlight on South Africa could also serve to highlight racial injustice at home, Robinson worked to marginalize the country’s all-white government on the global stage. Robinson had been involved in organized anti-apartheid work since 1959, and had delivered speeches supporting economic and cultural boycotts of South Africa for years.[7] Banned from the 1964 games, South Africa had been reinstated for 1968 after ostensibly easing some of the segregation policies on its teams. For Robinson and the OPRR, the change was woefully insufficient, and the boycott threat began to spread to African nations.[8]

In May of 1968, Avery Brundage announced that the South African team would be banned. Jackie celebrated the news in his May 11 Amsterdam News column, noting that the work of Black athletes—both in the United States and in Africa—made this possible.[9] He spared no ink in his condemnation of Brundage, whom he accused of “ignoring…apartheid as vigorously as he was attacking” those who threatened to boycott. For Robinson, this was a major victory. It showed that Black athletes still had the power to withhold their labor and fight for equality on a global scale. South Africa would not again participate in the Olympic Games until 1992.

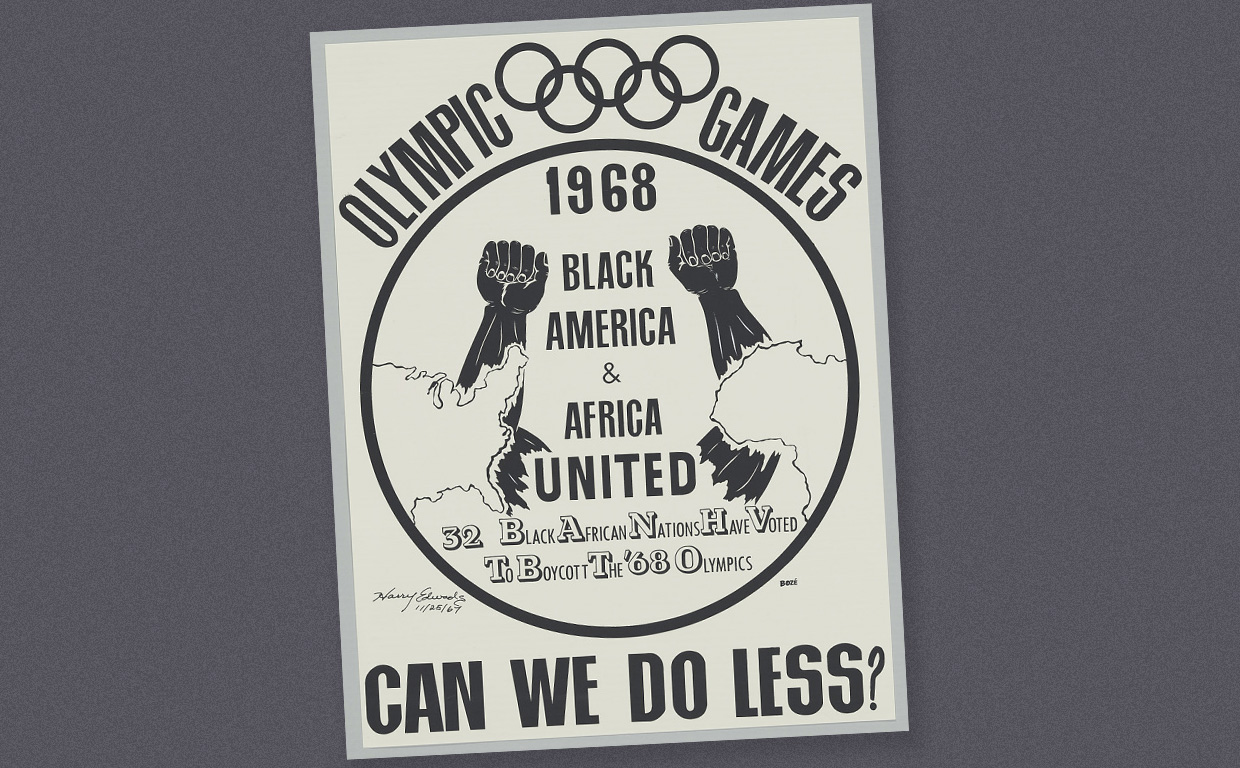

Olympic Project for Human Rights poster designed by Bozé and signed at bottom left by Harry Edwards, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Even though only one of the demands was met, the boycott did not go through as planned. Athletes were almost equally split on whether to go forward with the protest, short of the two-thirds required by a previous vote of the OPHR.[10] The NYAC remained segregated, Muhammad Ali was still regarded as a public enemy, and Avery Brundage would remain IOC president until his retirement in 1972. Even so, the Olympics produced powerful moments of protest. Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave Black power salutes on the podium after medaling in the 200 meters, resulting in a brutal crackdown on political statements from Avery Brundage and the International Olympic Committee.

For Robinson, the boycott was a chance for athletes around the world to show solidarity with victims of apartheid in South Africa and call out the hypocrisy of the New York Athletic Club. For Edwards and the Olympic athletes, the movement they built was an opportunity to test out new, radical strategies at the dawn of a more militant phase of the Civil Rights Movement. In an era in which the “old guard” was often criticized for rejecting the ideologies and tactics of the movement’s youth wing, Jackie stood up for his principles and his belief in the role of athletics as a site of political struggle. He organized allies, built connections, and lent his support to the athletes willing to risk their careers to demand global change.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE