News

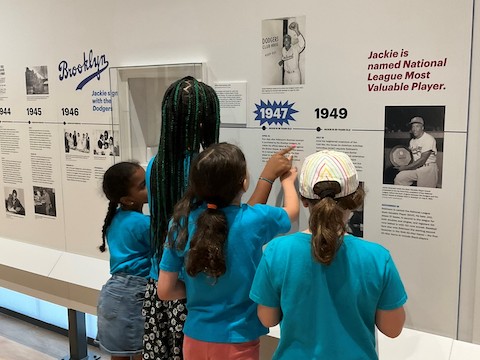

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Now booking summer field trips.

In 1947, when Jackie Robinson signed his contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, he told the waiting press, “I fully realize what it means – my being given this opportunity – not only for me, but for my race and baseball.” Throughout his life, he would insist that being the first Black person in a given vocation didn’t matter unless there were a second, third, fourth, or more to follow through the door he had opened. For Robinson, that meant supporting Black athletes across all sports—not just the men who followed him into the major leagues. One such collaboration was with trailblazing tennis star Althea Gibson, with whom Jackie Robinson worked closely during the 1950s and 1960s, as she strove to break down barriers in women’s tennis and golf.

Jackie Robinson presents Althea Gibson the 1950 Sports Achievement Award from the Harlem Branch of the YMCA at its annual Century Club dinner. Executive Director Rudolph J. Thomas smiles in approval. Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries

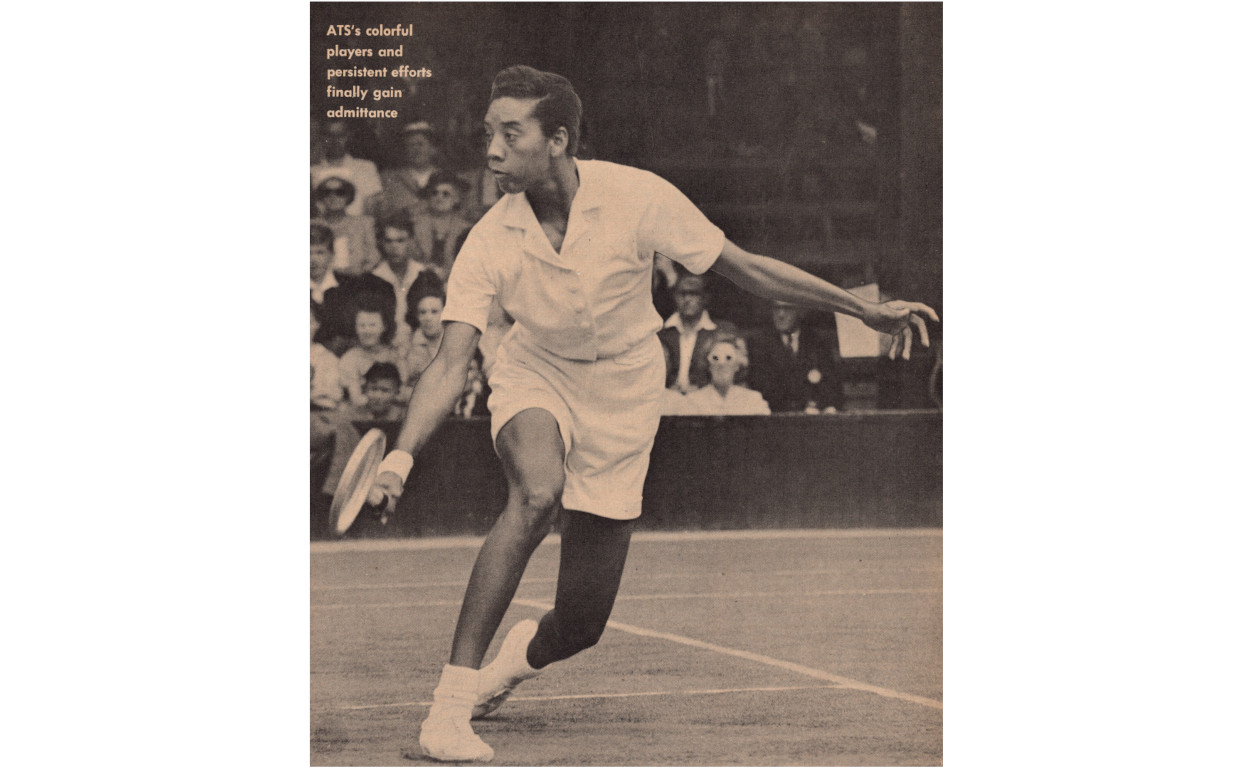

Althea Gibson won multiple singles, doubles, and mixed doubles Grand Slam titles across her amateur tennis career in the 1950s. After tennis, she turned to golf, becoming the first Black player on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour in 1964. Throughout her life, Gibson was confronted with Jim Crow barriers in both sports. In the early phases of her tennis career, even getting on the court was a challenge. To qualify for larger tournaments, players needed access to the highly segregated world of private tennis clubs, from which African Americans were frozen out entirely. Gibson was skilled—the entire tennis world knew it—but she did not receive an invitation to compete in the 1950 U.S. National Championships until a retired white player, Alice Marble, fomented public support for her inclusion. Over the decade, her legend grew—she won back-to-back Wimbledon singles titles in 1957 and 1958 and amassed three doubles titles there as well.

Althea Gibson shows Jackie Robinson her racquet grip at the American National Theatre Academy tennis tournament at the 7th Regiment Armory on February 16, 1951. Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images

In 1951, Althea Gibson joined Jackie Robinson in a celebrity tennis tournament to support the American National Theatre Academy. While the event might have featured more goofs and gimmicks than actual tennis competition, it was a chance for Robinson to support a rising star in a white-dominated field. Robinson himself was a competent tennis player. In 1936, he won a junior singles title at the Pacific Coast Negro Tennis Tournament, and he was victorious in both men’s singles and doubles in the Black Western Federation of Tennis Clubs tournament in 1939, even though he only played when not busy with other sports.

Althea Gibson receives a ticker-tape parade in New York on July 11, 1957. The Detroit Tribune

Prior to the Open Era in tennis, major tournaments such as Wimbledon were restricted to amateur players, who were not permitted to accept prize money. As a result, Gibson struggled to make ends meet, despite holding multiple Grand Slam titles and being honored with a ticker-tape parade in 1957. She turned pro in 1958 but found opportunities there to be equally lacking. Businesses were uninterested in sponsoring a Black player, and the prize money from tournaments was still small. “I saw that white tennis players, some of whom I had thrashed on the court, were picking up offers and invitations,” she later wrote in 1968. “Suddenly, it dawned on me that my triumphs had not destroyed the racial barriers definitively…Or, if I did destroy them, they had been erected behind me again.”2 Like Robinson, she tried to supplement her income with other ventures. She tried her hand at singing and acting, participated in exhibition tours, and published an autobiography. Nonetheless, commercial success eluded her.

Jackie Robinson and Althea Gibson examine a scorecard at the North-South tournament in February 1962. Bettmann Archive, Getty Images

Gibson hoped that more opportunities awaited her in golf. As she sought to enter the top ranks of a new sport, she received even more brutal Jim Crow treatment than she had in her tennis career. She competed at country clubs at which she could not use the dressing room or eat in the restaurant. Adding to her personal struggles, golf didn’t pay the bills. Nonetheless, she took joy in the game and participated in celebrity tournaments. In 1962, Gibson competed in the North-South golf tournament in Miami, alongside Jackie Robinson and retired boxer Joe Louis. Robinson and Gibson won the men’s and women’s tournaments, respectively. That summer, the pair teamed up against Louis and Ann Gregory, another top Black golfer, at a celebrity match held just outside of Chicago. Again, Robinson and Gibson emerged victorious, showing both players’ strengths as multi-sport athletes. Gibson went on to earn her LPGA tour card in 1964, making her the first Black golfer to do so.

Althea Gibson appears in the May 1953 issue of Our Sports. Edited by Jackie Robinson, Our Sports was a magazine that highlighted Black competitors – including women – in a wide variety of sports alongside professional ballplayers. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Althea Gibson’s renown as a barrier breaker—in two sports—often went unheralded in the press, let alone in her pocketbook. Still, she was an inspiration to Black athletes, especially women, in an era when the Civil Rights Movement was still in its infancy. Both Althea Gibson and Jackie Robinson used their status to promote desegregation in American sport. Unlike Robinson, Gibson was much less outspoken about the growing fight for civil rights. As she was racking up accolades, she often struggled to talk about how her triumphs and misfortunes were reflected in the broader American society. She was criticized often in the Black media for her lack of public participation in the movement, especially as later Black tennis stars, such as Arthur Ashe, were more outspoken. Even so, the power of Gibson’s legacy is undeniable; Black women tennis stars, such as Venus Williams, Serena Williams, Naomi Osaka, and Coco Gauff, dominate on the global stage today, made possible by Gibbs’ pioneering efforts in the 1950s and 1960s.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE